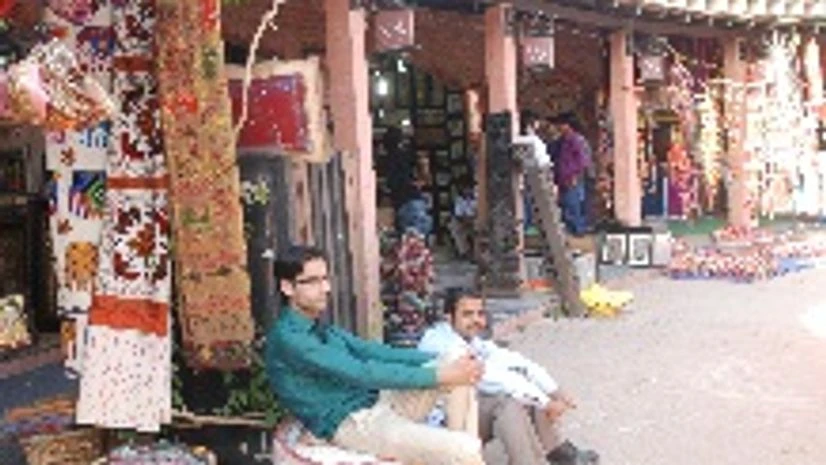

Even on a sweltering April day, Dilli Haat is bursting at the seams with eager shoppers. The ongoing Nepalese handicrafts show is proving to be quite an attraction, with noisy gaggles of young women thronging to the metal work and bamboo handicraft stalls. If you look closer, past the gleeful crowd or the exquisite wares from Nepal, you will experience a sense of déjà vu. As you walk around the open-air space, the same old chikankari kurtis, Naga shawls, Kashmiri phirans, organic pickles and block printed saris lie on show in the stalls, waiting to charm buyers for the umpteenth time. The artist that you had seen sketching profiles of young kids a month or two ago is still there. So is the man who engraves names on rice.

The space that was established in 1994 as a platform for artisans from the remotest corners of the country to showcase their skills is sadly losing its sheen with customers complaining of rampant commercialisation and dubious quality of wares. The old-world charm of the bazaar is ebbing away, the prices are skyrocketing, with some kurtis and saris being sold at the retail rates that one usually encounters at Fabindia or Anokhi, and the once-incredible variety has whittled down to a boring sameness.

It’s surprising to know that some of these artisans are a fixture at the Haat all year round, with some even being residents of Delhi and not from the state where the craft originated. Earlier this year in January, one chanced upon a kiosk selling hangings, pots and home décor pieces made using the pasting painting technique. While the pieces were worked on by artisans in Pune, the owner of the stall was Delhi-based and was selling these wares under his brand’s name. This defeated the founding principle of the Haat, which was to create a domestic crafts supermarket, thus enabling talented artisans to sell their wares directly to the customers, without the middleman pocketing a chunk of their earnings.

Jaya Jaitly, former president of the Samata Party and founder of the Dastkari Haat Samiti, too laments about the state of the bazaar. She stirred up a hornet’s nest recently by alleging gross irregularities in the administration of the marketplace. Jaitly had helped conceptualise and set up the venture which was supposed to combine the elemental setup of a rural haat with the sophistication of an urban marketplace. Reasonably priced entry tickets, low stall rentals and a rotational structure (a fortnight’s occupancy per craftsperson) went on to become the cornerstones of its success. “However, its basic premise — based on the rotational allotment of 182 stalls through a lottery system for subsidised rent — is being flouted brazenly by either forgery of allotment letters or registration under multiple names to enable repeated allotments,” she claims,

“Traders have often called in political favours or paid off genuine allottees to sublet their stalls.”

She further says that Delhi Tourism, which created the market’s infrastructure with New Delhi Municipal Corporation and the ministry of textiles, has turned this not-for-profit venture into a commercial hub with brand promotion kiosks and makeshift stalls rented out at Rs 30,000 per fortnight, often bowing to arbitrary bureaucratic decisions masked as “policy” or “financial” decrees. There are even claims that machine-made products have managed to slip in and are masquerading as handicrafts.

The way forward now, according to Jaitly, is to formulate fair rules and regulations, and to implement them strictly. For instance, an online system of registration, which is clean, precise and transparent, could be a possible first step. Here’s hoping the spirit of the bazaar heals and the picture that it once painted as an embodiment of India’s cultural heritage soon emerges from beneath the grime.

)