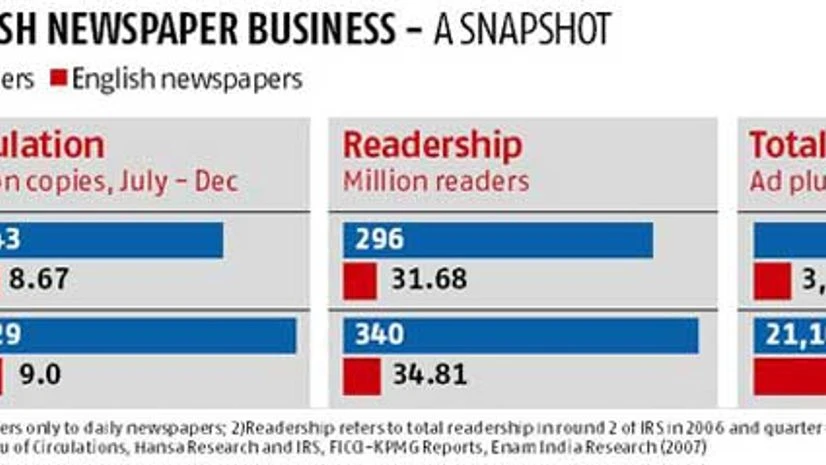

Has the decline of English newspapers in India begun?The signs have been flashing red for a while now. On circulation, readership and time spent, English newspapers have not been doing very well, especially when compared to papers in other Indian languages which are booming (See chart). While English newspapers' share of the total revenue pie has increased to Rs 8,200 crore in the last seven years, this has come on the back of higher rates rather than more readers. "The latest Indian Readership Survey (IRS) shows less than one per cent growth. There is resistance from readers," says N Ram, director, Kasturi & Sons, the publisher of The Hindu. "Growth is slower," agrees Ravi Dhariwal, CEO (publishing), Bennett, Coleman & Company, or BCCL, the publisher of The Times of India, among other brands.

To this dismal mood add a faltering economy, slowing advertising growth and rising digital penetration. At last count, more than 124 million Indians were online-on their computers, notebooks, phones or other devices. These people are the prime target for English newspapers. As they move online, advertisers are trying hard to catch them while they surf, watch films, read or meet friends. Digital advertising rose by a whopping 41 per cent in 2012 over 2011, albeit on a smaller base than print which grew by 7.6 per cent in the same period.

A similar combination of factors has annihilated newspaper industries in mature markets. The total revenues for the American newspaper industry shrank from $60 billion in 2005 to $33.8 billion in 2011 even as paid circulation tumbled from 53 odd million to just over 44 million copies. This happened largely because readers went online. The same thing "is bound to happen in India. The question is when. I don't know what the tipping point could be, 200 or 250 million (online users)," says Ram.

Many publishers, advertisers and media buyers however argue that the way to battle potential stagnation and decline in English newspapers is not just online-it also lies in expanding the market. "If English print has to grow, it has to go to small-town India," says K Satyanarayana, vice-president, R K Swamy Media Group.

But first a look at why the English reader is fading out.

"I wouldn't look at circulation growth for English newspapers as an indicator because most of the new entrants in the national space such as DNA are not in ABC (Audit Bureau of Circulations), nor are we," points out Dhariwal. That may be true, but even if those numbers were factored in, English readership and circulation is barely growing. Dhariwal reckons that "English newspaper behaviour is a reflection of consumer behaviour in the metros which is changing because of the paucity of time. So, casual readership is increasing but not loyal readership."

And this brings us to the first of the three reasons why growth remains a reality in the Indian print market. The headroom for growth is huge given that penetration is so low. Just about 350 million people read a newspaper in a country which has more than 895 million literates. Not just English, reading itself is an aspirational activity in India. So while English papers are losing the young in metro India, they are gaining them back in small-town India where many have been expanding. "Our readership is largely metro but circulation and readership in small towns is increasing too," says Dhariwal. The Rs 5,500-crore BCCL makes a chunk of its revenues and profits from The Times of India's Mumbai edition.

The market size, growth rate and the reverential space that print occupies in India means that unlike the US or UK, the Rs 22,400-crore print market in India is more profitable and stable than television. Mona Jain, CEO, Vivaki Exchange, a media buying firm, points out that falling growth in readership has made English media brands, "more flexible. Rate cards are no longer sacrosanct." This has pushed even typical TV advertisers such as FMCGs into print's arms. Add to this the impending rate increase in television because of the ceiling of 12 minutes of advertising per hour on TV. It is forcing many advertisers to look at print "not just for tactical but also for strategic brand building campaigns," says Jain.

Lastly, in the US or UK, a bulk of the sales come from the readers picking up a paper at the newsstand. So there is volition involved. In India a bulk of the sales come from home. Till it is economical to deliver papers at home, it will be difficult if not impossible to dislodge dailies from the family's media basket. It is, say publishers and analysts, the single biggest reason newspapers in India will thrive longer than elsewhere.

These three reasons explain why most analysis of print markets across the world pegs the decline of print to start 10-20 years down the line in India.

The worrying part, however, is that, just like most of their global counterparts, none of the major Indian newspaper groups has met with any success in its digital efforts. "We got in very early on the net but don't think that we or anybody else does as well online as The Guardian or The New York Times. We are nowhere close to breakeven," says Ram. For instance, after more than a decade of being online, The Hindu and its sibling brands notched up Rs 4.35 crore online in the financial year ending March 2013. That is 4 per cent of Kasturi & Sons total estimated revenue of Rs 1,100 crore in the same year. Others average anywhere between 3 per cent and 5 per cent of their topline from online.

What newspaper publishers can do is keep trying to use this period of high growth and profitability to sow the seeds for an online future. But, as Dhariwal puts it, there is "no silver bullet for online."

)