It was around the mid-1960s when the Paddock brothers, the ‘prophets of doom’, predicted that in another decade, recurring famines and an acute shortage of foodgrain would push India towards disaster.

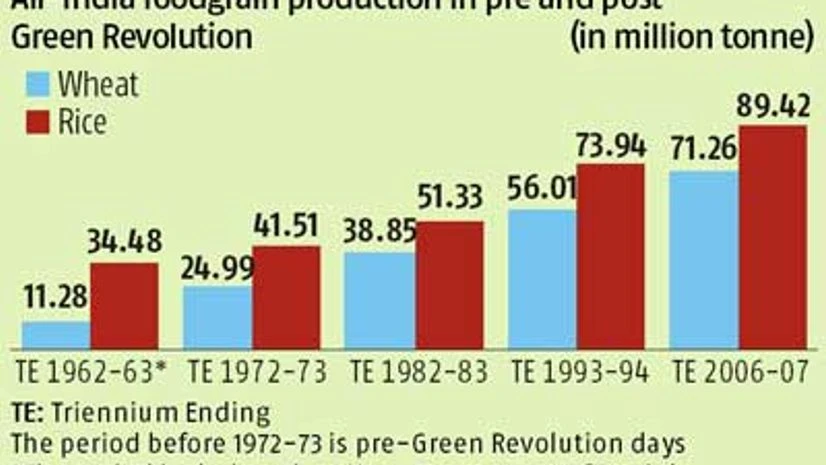

Their prophecy was based on a rising shortage of food because of droughts, which forced India to import 10 million tonnes of grain in 1965-66 and a similar amount a year before. Little did they know that thanks to quick adoption of a new technology by Indian farmers, the country would more than double its annual wheat production from 11 mt during the triennium ending (TE) 1966-67 to 23 mt during TE 1971-72, and raise its rice production 30 per cent in the same period.

In the four decades starting 1965-66, wheat production in Punjab and Haryana has risen ninefold, while rice production increased by than 30 times. The twin states and parts of Uttar Pradesh now not only produce enough to feed the country but to leave a significant surplus for export.

The technology and the subsequent state support is perhaps the single vital event that changed the face of Indian agriculture. At a time when the country is to mark the golden jubilee of that momentous event, it is also time to look back at the gains and losses from that revolution.

Then & now

“The green revolution helped India move out of a ship-to-mouth situation and India was made self-sufficient in food production but since the mid-1980s, its second-generation environmental impact and the intensive farming it promoted started showing its impact. We've now reached a stage where we need to understand that the green revolution has done its job and it's time to consign it to history, and shift to a more sustainable method of farming," says noted food policy analyst Devender Sharma.

M S Swaminathan, considered ‘father’ of the change, said, “Almost 50 years ago, we had to import wheat and rice. This year we are about to import 10 mt of pulses, despite being its original producer. The reason is, we could not take good care of pulses. What disturbs me today is that there is no green revolution. Those days we adopted modern technologies but now we have to move towards a more environmentally sustainable agriculture. I am not satisfied with the condition of farming in the country, as there are too many barriers to the movement of goods. In the report of the National Farmers Commission tabled in 2005, we had talked about having a common market. The Centre’s concept of a common market will solve some of the issues, but not all.”

S Mahendra Dev, director of the Mumbai-based Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, said he regarded the single biggest contribution of the green revolution as the raising of the yields of wheat and rice, saving much land from being converted for agriculture, apart from, its contribution to our food security.

Its biggest drawback, he said, was its limitation to a few states, promotion of mono-cropping and encouraging the use of more chemical fertiliser. These associated issues should have been addressed, too.

Around the time, the Paddocks predicted doom for India, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre in Mexico came out with a high-yielding variety of wheat. Followed by a similar breakthrough at the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines. These twin technologies were adopted here to boost domestic production.

Alongside, a well-oiled mechanism of price assurance to producers through a system of Minimum Support Prices, implemented through obligatory procurement, inter-year and intra-year price stability through open market operations and distribution of subsidised foodgrain through a network of ration shops was put in place.

All these changed India from a grain-deficit state to one of the world’s biggest producers today of wheat and rice. The entire north-western region of Punjab, Haryana and western UP were early adopters of the technology, as land in these parts was suitable for adoption of new varieties, water was abundant and farmers were willing to alter their cultivation patters.

“It is because of the green revolution that big gains have been made in India’s food production capacity. Also, our research capacities and its spread have improved tremendously, a vital offshoot. But, managing the other challenges like that of water, etc, has not been up to the mark, which cannot be blamed on the green revolution,” said Shashanka Bhide, director of the Madras Institute of Development Studies.

Challenges

Balancing its benefits to all farmers, across all crops, has been weak, he noted. Critics say indiscriminate use of fertiliser, excessive exploitation of groundwater, driven by cheap power, and difficulty in adopting new farming patterns is gradually turning barren the erstwhile green revolution belt.

Studies show the net annual groundwater draft in Punjab exceeds availability by 45 per cent and in Haryana by nine per cent. Indiscriminate use of fertiliser due to massive subsides has changed the nutrient balance in the soil. As against the N:P:K norm of 4:2:1, farmers in Punjab and Haryana apply these in the ratio of 26:7:1 and 37:11:1, respectively.

In sum, promoting the green revolution here and elsewhere in a sustainable manner, unlike till now, is the need.

)