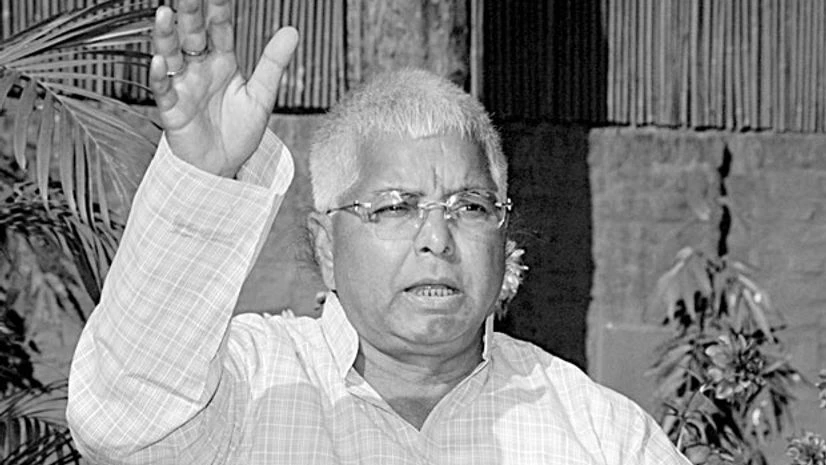

Lalu Prasad Yadav

If you’re a liberal Indian who believes in democracy and a welfare state, is conscientous about paying taxes and is convinced that the socially powerless must be empowered, then Lalu Prasad represents a political problem.

Here’s the thing: caste lives in India and the rise of Lalu Prasad, who belongs to the Yadavs, a middle caste of milkmen that is low on the social register but is politically volatile in Indian politics, represents the rise of a set of people who have spent much of independent India’s 60 years believing that they are doomed to live outside the charmed circle.

Also Read

A politician from Prasad’s caste described what being a middle caste in rural India means. “When we cycle to the village,” she said, “we have to dismount before we reach the landowner’s house. Otherwise his servants think we’re trying to defy him, trying to prove we’re his equals. There was a time they used to come after us. That no longer happens, but we still dismount.” This is a voice from a caste that is economically better-off than the really downtrodden. Of the stories the Dalits—the lowest in the caste hierarchy—have to tell, the less said the better.

Suffice it to say that upward social mobility means everything for this caste group in India. And its empowerment came about because of the movement launched by Lalu Prasad.

Good governance? That’s a secondary matter.

Lalu Prasad first came to power in 1990 as chief minister of Bihar, the state with a reputation for being poorly administered and endemically problem-ridden despite being blessed with fertile soil and plenty of river water. He belongs to the first generation of Indian politicians with no experience of colonial rule, being born in 1948, a year after the British left India. He began his political career, not with the high-minded idealism of the country’s freedom movement, but in the rough-and-tumble of student politics that gripped India in the troubled 1970s when economic growth was slow and inflation high. This coloured his language, his style, his satirical style of oratory, and his rustic if lumpen brand of politics.

After nearly two decades in the opposition, Prasad rode an anti-Congress wave to power. A milkman’s son replacing the state’s Brahmin chief minister! All of Bihar’s low castes wanted to be him. He was a symbol of their hope.

On the strength of these feelings, Prasad was re-elected in 1995, but forced to step down in 1997 after being indicted for corruption in a case involving millions of dollars meant for a government programme to buy cattle fodder for giving the poor. The money found its way into the pockets of bureaucrats and politicians. Being shrewd enough to understand that resigning from office could spell political oblivion, Prasad pulled off the neat trick of getting his party to choose his unlettered and completely inexperienced wife to succeed him as chief minister.

His wife and he therefore ruled for 15 years, a period in which Bihar sat on the bottom rung of every socio-economic ranking in the country. Land reforms remained an incomplete revolution. Anything remotely resembling an industrial revolution passed the state by. It was almost as if there was a trade-off between the empowerment of the socially backward and economic progress. “Why do we need cars,” Lalu would ask his voters, “when Bihar has no roads? And the poor use (oil-burning) lanterns, so what will you do with electricity?” To the modern mind, it was politics as caricature. But also as tragedy, because law and order had collapsed in the state capital of Patna, kidnapping for ransom was a growth industry, the health services suffered for want of medicines, and the government had no money to pay university and school teachers—who retaliated by not holding exams on time. Private armies organized along caste lines mushroomed. Bihar was slipping back into the middle ages.

These are the more serious aspects of Lalu Prasad’s rule. There are others on which he built his reputation as an attractive country bumpkin. A big controversy that broke out somewhere in the middle of his rule related to a Bihar School Examination Board's question paper for Class VIII, which had questions like the following:. "Why is Laluji's personality an open book? What is that attribute of Laluji which spontaneously attracts people towards him? Why is Laluji regarded as the frontrunner of communal harmony?"

Sushil Kumar Modi, then leader of the opposition in the Bihar assembly, now Deputy Chief Minister of Bihar and others demanded "severe punishment" for the person responsible for setting such questions. They also objected to as many as five questions on Prasad - which could have fetched 10 marks - against one question each on Lord Mahavir, Mahatma Gandhi, Jayaprakash Narayan and Munshi Premchand.

But Bihar primary and secondary education minister Ramchandra Purve found their objection "foolish". "We have not written in the question paper that Nathuram Godse is the founder of the Indian Constitution", he said asking the opposition not to make such a hue and cry about "very appropriate questions set in the 8th class question paper".

He continued: "Lalu Prasad is a messiah of the poor. The masses love him. He is an epitome of communal harmony. He has given voice to backward classes and Dalits and safety to minorities. These are the realities of Lalu Prasad. Why should the opposition react on the questions based on realistic themes?"

The opposition wasn't at all surprised at this defence. This was the same Ramchandra Purve who'd equated Lalu Prasad's journey to Ranchi jail in connection with a fodder scam case with the historic Dandi march of Mahatma Gandhi.

Purve was not alone. Another small-time leader, Brahmanand Paswan, penned what was called Lalu Chalisa along the lines of the Hanuman Chalisa. Lalu Prasad described him as a modern day Ramdhari Singh Dinkar, one of India’s most renowned Hindi poets and made him a Rajya Sabha MP.

Rambachan Rai wrote an article in praise of Lalu Prasad. The government introduced this in the Bihar Secondary School's syllabus for Class VIII. And it appointed Rai chairman of the Hindi Pragati Samiti.

Similarly, Shankar Prasad, a folk singer, composed and sang several panegyrics for Laloo Yadav and Rabri Devi. One of them was: "Marachia ke mai ke tu lal bara ho; Ai Lalu jor naikhe neta tu bejor bara ho (You are a hero born to Marachia Devi; O Lalu, you have no peer, you are peerless)." RJD workers used Prasad's songs in election campaigns. And impressed with his "cultural qualities", Laloo Yadav got him appointed chairman of the Sangeet Natak Academy.

Again, Amar Kumar Singh was not known as a writer of any worth till he penned a biography of Lalu Prasad Yadav titled Gudri ka Laal (Diamond from tatters). Impressed by his work, Lalu Prasad got him appointed chairman of the Bihar Hindi Granth Academy. Another, Anwar Ali, was made a member of the state legislative council. Rashtriya Janata Dal workers used to describe Ali as a "kebab mantri” (kebab minister) for he used to prepare kabab and biryani for Lalu Prasad and his family. So it was an idyllic existence for the family.

But storm clouds could not be ignored. They were gathering rapidly. Bihar used to send 54 seats to the Lok Sabha. But the cry for smaller states had gathered ground and the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM) was seeing on the horizon, a chance of its ambition to rule in a state dominated by tribals. Although the Bihar Assembly finally voted in favour of the bifurcation at first Lalu Prasad resisted, and said the state would be divided “over my dead body”. Later, he had to give in. Jharkhand came into being on November 15, 2000. 14 Lok Sabha seats were moved to Jharkhand, so Lalu Prasad’s political clout dipped.

The bifurcation had a disastrous effect on Bihar’s economy. Its population was increasing, the mineral based industry, the sector that earned revenues for the state, all went to Jharkhand. What remained with Bihar was its poor population, a massive budget deficit and very fertile land but with poor water management and very high density of population dependent on it. There should have been changes in the cropping pattern of Central Bihar from traditional cropping to cash crops but this didn’t happen. Already poor, Bihar became poorer.

By 2004, a tired Lalu Prasad struck a deal with a weakened Congress. They fought the parliamentary elections together and his Rashtriya Janata Dal won 23 seats in the Lower House (out of 40 in Bihar). This gave him the licence to leave his state and come into his own on the national stage. He asked for and got the railway portfolio, the railways being by far the largest single enterprise in the country, employing 1.5 million people and moving 1 per cent of the country’s billion-plus population every day, apart from 40 per cent of its goods traffic.

And Lalu took the country by surprise. He transformed the moribund organization in a way that no one had predicted, and suddenly Lalu Prasad was a hero to all those who had shaken their heads at the mention of his name. And what a transformation! The same man who is held single-handedly responsible for the quagmire called Bihar, managed to improve productivity and profits, and has now embarked on a massive investment and modernization programme.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh recalled once that he had told his newly appointed railway minister in 2004: “Laluji, you should think of giving the country a rail system India can be proud of. It will also do wonders for your reputation.” Given what people thought at the time of Lalu Prasad and his capabilities, it would have called for considerable optimism to think that the new minister could even think in terms of modern systems. But rustics who come across as comics (and if Lalu knows anything, it is how to play to his audience) can also hide shrewd brains. And sure enough, Lalu showed a new set of colours.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh recalled once that he had told his newly appointed railway minister in 2004: “Laluji, you should think of giving the country a rail system India can be proud of. It will also do wonders for your reputation.” Given what people thought at the time of Lalu Prasad and his capabilities, it would have called for considerable optimism to think that the new minister could even think in terms of modern systems. But rustics who come across as comics (and if Lalu knows anything, it is how to play to his audience) can also hide shrewd brains. And sure enough, Lalu showed a new set of colours.

On a surprise inspection of a railway loading site, the new minister found that most railway wagons were being routinely overloaded. The railways got no money for this excess freight, and its staff were probably taking bribes for allowing the overloading. Lalu decided that if the wagons and track could carry the extra load, he should raise the official loading limit—so that even the existing loading levels would bring extra revenue to the railways. Since the overwhelming bulk of the railways’ costs are fixed overheads, any additional revenue that the railways booked made little difference to costs, and the extra money went straight to the bottom line. Suddenly, the railways became hugely profitable.

Lalu has also had the good sense to not interfere with the day-to-day running of a massive system, doing nothing more than giving broad directions and leaving the rest to competent railway officials. What he did do, though, was to bring in a hand-picked official or two from his native Bihar to be his eyes and ears, and to take key decisions.

The man who used to say in his election speeches in Bihar that he needed to be brought back to power because the lower castes owed it to him, now sounded like a corporate CEO when he told Parliament that, with a return on capital employed (ROCE) of 21 per cent, the Indian Railways were as efficient as any global corporation. “Our achievement, on the benchmark of net surplus before dividend, makes us better than most of the Fortune 500 companies in the world,” he said in his budget speech in February 2008.

It wasn’t that he never put a foot wrong. For instance, he pledged to Parliament that he would turf out AH Wheeler, the chain of bookshops ubiquitous on railway platforms, because he thought they were an English legacy. It turned out that the company, which gave Rudyard Kipling his first publishing break, is now fully owned and managed by Indians. Lalu Prasad has also not been above a little window-dressing, presenting the accounts in a new way to exaggerate the increase in surpluses. But there is no questioning the fact that the railways are now financially healthy, investing heavily in modernization and increasing capacity: new track, better signaling, faster trains. So much so that the railway turnaround has become a textbook case, and B-school students from some of the best American universities now have Rail Bhavan in New Delhi on their study tour itineraries.

So why had Lalu Prasad not tried to improve governance in Bihar? This will remain one of the enigmas in Indian politics. Perhaps he was caught up in the politics of courtiers. Or he did not have a good team to assist him. And may be he thought that when he was getting by with so little effort, why bother?

One clue to the transformation of Lalu Prasad is the changed way in which he deals with officials. In Bihar, he would over-rule them. In Delhi, he defers to them, and listens to what they have to say. All very democratic. So does that mean democracy in Bihar works differently from democracy in Delhi? Perhaps not, because the present chief minister of Bihar, Nitish Kumar, is trying to improve governance in the state and showing results too. Perhaps it is simply that politicians of all hues have realized that the key to success is through performance.

But now Lalu Prasad is slowing down. He told his supporters at a party meeting recently: “I have made a name for myself, I have enough money and I will have settled my family by the time the next assembly elections in Bihar come around. My future is secure. You should all look out for yourselves”.

The old Lalu would not have countenanced the almost audacious suggestion of Ramvilas Paswan that Lalu was past it and should make way for younger leaders (like himself). Lalu Prasad replied to it in characteristic fashion, loaded with satire and sarcasm. Ramvilas ji is a mass leader, he told reporters and everyone in Bihar knows him. I will most certainly step aside for him and his nine MPs.” (Lalu Prasad has 23).

His handling of the 2008 Bihar floods showed that the ground was shifting under his feet. Floods in the Kosi river caused an unprecedented scale of misery in the state. At first Lalu Prasad was trenchant about his rival, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar’s handling of flood relief. But when three member of Parliament from Nitish Kumar’s party resigned from their seats, alleging the centre’s discrimination in providing relief to the state – and Lalu Prasad was part of the central government – he took one step back. The fact is, leveraging Indian Railways, Lalu Prasad had managed to send vast amounts of rations, clothes and tents, etc to Bihar. But the problem was, he had to be present to ensure its distribution. Chary of letting someone else hog the credit, Prasad was unwilling to delegate the task of relief distribution. So much of relief was sitting in the Rashtriya Janata Dal office, waiting to be distributed.

In the current scenario, he has limited political utility for the UPA. In the run up to the demolition to the Babari Masjid, BJP chief LK Advani undertook several rathyatras including one to Bihar. At that time (1990-91), Lalu Prasad’s Rashtriya Janata Dal was a part of the VP Singh-led National Front government at the centre that the BJP was supporting from the outside. After a great deal of dithering, Lalu Prasad ordered that Advani be arrested in Samastipur, but (and this we now know, on the testimony of current Home secretary of Bihar Afzal Amanullah) lacked the courage to have him arrested. Amanullah was posted as the Deputy Commissioner of Dhanbad and refused to arrest Advani as clear orders were not given because Lalu Prasad was in touch with VP Singh who feared the government at the centre might fall as a result of such a move. In fact it did, but the incident revealed Lalu Prasad’s duplicity on the matter of secularism.

But that apart, arresting Advani got Prasad tremendous traction from the Muslims in Bihar and he basked in that glory for years later. At that time Muslims were frightened and nervous and hailed Prasad’s action as an unparalleled act of heroism. Today, when the communal situation is not that polarized, Lalu Prasad’s following among the minorities has shrunk. Instead, recognizing that it was the upper caste, affluent Muslim elite that had kept Lalu Prasad in power, Nitish kumar drove a stake among them and called out to the most backward Muslims to support him. There are several villages in Bihar that are Muslim-dominated that have done the unthinkable: voted for the Lotus because they think that is the way to bringing Nitish Kumar to power and subsequent Muslim empowerment. The kind of polarization that was seen in the later part of the 1980s and early part of the 1990s is nowhere to be seen now. So Lalu Prasad’s USP with the Muslims has been challenged.

But he’s fighting to retain the support the community. One of the most important elements in his political campaign is going to be yatras in Musmil dominated areas with just a picture of LK Advani. His advisors reckon that when Muslims are reminded of the days of 1992, they will revert to Lalu.

This is not the only thing that has hamstrung him and curtailed his capacity for political intervention. His party was run by him, not by any democratic principles. This was fine when the times were good and he could deliver. But now, when his fortunes are clearly being eclipsed, his party’s base is also shrinking. Lalu Prasad’s greatest asset is his oratory, his village bumpkin political style. But this has limited appeal in a scenario where his rival Nitish has introduced a new element: good governance.

As in other parties, in the RJD too, the son has risen. Tejasvi, his son is now heir apparent in the party, the person who will take the party forward. But Tejasvi is not Lalu. And there are others laying a claim to the leadership of the RJD and the Yadav clan, including his brother Tej Pratap.

Is Lalu Prasad finished as a force ? It is too early to tell. But Bihar is certainly the poorer for it.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

An earlier version of this article appeared in 'Of Cabals and Kings' published by BS Books 2009

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

An earlier version of this article appeared in 'Of Cabals and Kings' published by BS Books 2009

)