From postponing a hike in railway fare to promising doubled farmers' income in the next five years, from the prime minister holding a number of farmers' rallies to renewed focus on augmenting rural growth and enhancing allocation for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee scheme in the Union Budget, the National Democratic Alliance government is resetting its economic agenda to make it more palatable to the depressed sections of society.

Following the presentation of the Budget, senior functionaries of the Narendra Modi government even went on a media overdrive to highlight what they termed as a pro-farmer and pro-poor focus.

The prime minister has reportedly urged members of Parliament of the ruling coalition to go to their constituencies to publicise the newly launched crop insurance scheme and other pro-poor initiatives of the government.

Will a reset of the economic agenda help the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) electorally? If data from past elections are any indication, the BJP may need more than economic policy reorientation to win hearts and votes of the poor.

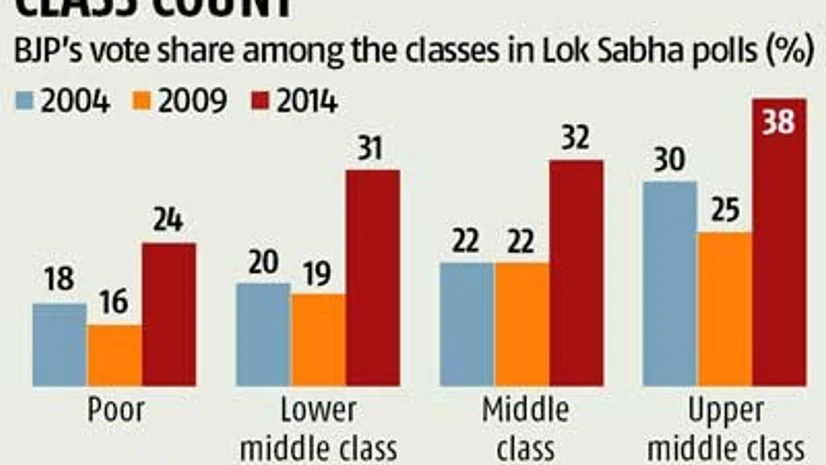

According to Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) data, in all Lok Sabha elections since 1996, the BJP has got fewer votes among the poor and the lower middle class than its share among the middle and upper classes. The party's vote share among the poor ranged from a low of 13 per cent in 1996 to a high of 18 per cent in 2004.

Data suggest that the saffron party has not done well among the lower middle class, too. Between 1996 and 2009, the BJP could manage roughly one-fifth of all votes of the lower middle class in all Lok Sabha elections during this period. The 2014 general election, however, was different. While the poor continued to be somewhat lukewarm towards the BJP, the lower middle warmed up to the Modi-led BJP for the first time.

"2014 was different. A combination of many factors worked for the BJP. But it should not be assumed to be a permanent feature. The BJP managed to cobble together a loosely knit coalition of disparate forces," observes CSDS director Sanjay Kumar, who has authored many scholarly papers and books and has covered elections in the country for more than two decades.

As against the BJP's vote share of 31 per cent in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the party could get just 24 per cent of poor votes. It, however, got 31 per cent votes of lower middle class, 32 per cent of middle class and 38 per cent of upper middle class votes, according to CSDS data. Incidentally, the BJP had talked about neo-middle class ahead of the 2014 Lok Sabha polls and the campaign pitch may have helped the party win over a sizeable section of lower middle class voters.

According to CSDS classification, the upper middle class constitutes 11 per cent of the country's population, the middle class 36 per cent, the lower middle class 33 per cent and the poor 20 per cent.

Political commentators say that the muted response of the poor towards the BJP is a result of inherent caste/class contradictions in our society. While the BJP's aggressive espousal of Hindutva makes it's a favourite among the upper castes, the same set of worldview may have alienated other social groups, they argue. "So many disparate groups voted together for the BJP in the 2014 Lok Sabha polls does not mean that social division has disappeared," argues Kumar.

Juxtaposing caste wise break-up of CSDS data with class-specific voting pattern, it becomes clear that even in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP got fewer voters among poor OBCs (other backward classes) and all sections of the scheduled castes.

)