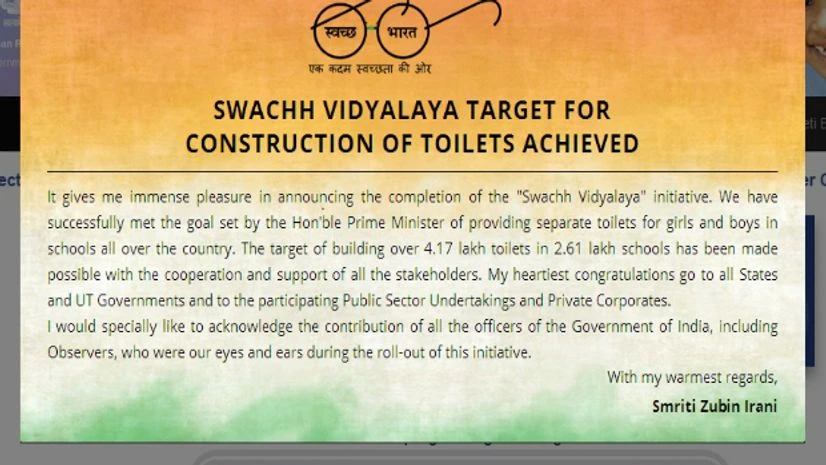

A visit to the Swachh Vidyalaya website on Independence Day, one is greeted with a congratulatory message on the completion of the Swachh Vidyalaya (SV) campaign (launched to ensure toilets including separate ones for girls in all schools). The message is accompanied with a bar measuring 100% completion rate of a target of constructing 4.17 lakh toilets in 2.61 lakh schools across the country.

Similarly, the launch of the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) to ensure financial inclusion was accompanied with the creation of the PMJDY portal to track progress. A look at the numbers indicate that in a span of 1 year, over 17 cr accounts were opened, 15 cr debit cards issued and less than 50% of accounts had 0 balance.

Whilst the successful achievement of the targets for PMJDY and SV campaign are indeed significant and should be lauded, their very “success” points to some fault lines in government’s management information systems which should not be ignored in the celebrations.

Let me elaborate what I mean.

The Mission Mode Model

Also Read

As early as October 2011, the Supreme Court (SC) of India had directed all States and UTs to build toilets, particularly for girls in all government schools by the end of November the same year. At the same time, the annual computerised system to collect school level data including the number of toilet facilities was also already available through District Information System for Education (DISE). In fact, if one was to look at the programme pre and post Swachh Bharat, the only noticeable difference between 2011 and today is that a) there is a lag between DISE data collection and publication (till today, latest DISE data available is for 2013-14) and thus there was no regular portal monitoring real time progress, and b) there was no significant political push for the programme.

The fact that only when the entire machinery was mobilised in mission mode for a specific goal, were results fast-tracked is indicative of systemic weaknesses in the existing planning, implementation and decision-making processes, that need to be addressed.

The Output Model

Another important fault line relates to what we are measuring, or rather, what we are able to measure regularly. As a country, we are relatively good at monitoring targets related to inputs and outputs. And interestingly, by design, both programmes (SV and PMJDY), the focus has been on monitoring progress on number of toilets built or number of accounts opened. Little information is available on whether these toilets are increasing attendance, or whether accounts opened have had an “impact” on easier access to benefits.

Whilst measuring outputs is important, for social policy programmes to succeed in the long run, a regular system for tracking outcomes will also need to be developed.

The Stick Model

The last important fault line ties into the question of incentives and usage of data. To give an example: a look at data published by DISE suggests that between 2011 and 2012, the proportion of schools with girls’ toilets increased from 72.2% to 88.3%. Interestingly however, during the same period the proportion of boy’s toilets decreased from 81.1% to 67.1%(Remember this was the time the SC was pushing for separate toilets for girls).

An off the record conversation with a state official provided some explanation: “The push to show achievements in girl’s toilets led the state to “convert” all existing toilet facilities into girl’s toilets!”

An off the record conversation with a state official provided some explanation: “The push to show achievements in girl’s toilets led the state to “convert” all existing toilet facilities into girl’s toilets!”

The problem is a simple one. If data generated by me is used primarily to monitor me, I am incentivised to report positively on it. Or to be less pessimistic – if I know I am being monitored on certain things, I will focus only on those things.

Most social sector schemes emphasize the need and importance of local level planning. Consequently, formats are made for collecting disaggregated data, numerous hours are spent by frontline workers filling formats (anganwadi workers are meant to fill 37 formats across 11 registers!) and computer operators at the block/district have the daunting task of turning 1000s of pages of data into monthly or quarterly reports to be handed over to their supervisors. But then what? What happens with the data? What is it used for? More often than not it is used only as a tool for monitoring performance. Rarely does it feed effectively to a planning process, or a process for identifying bottlenecks or a tool for the user to diagnose or learn from inefficiencies.

The new government seems keen to use statistics and data and create regular systems for monitoring performance. That is a positive step. However, for India to move towards a sound evidence based policy making system, we need a radical transformation in the manner in which we view and use data. In the words of Dr. Suresh Tendulkar we need a system “involving continuing interaction between data generators and data users so that demand for and supply of data are taken to be realistically inter-dependent and mutually interactive in character.”

Avani Kapur works as Senior Researcher: Lead Public Finance, Accountability Initiative at Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. Her work is focused on public finance & accountability in the social sector.

This is her first post on her blog, Social Specs, a part of Business Standard's platform, Punditry

Avani tweets as @avani_kapur

Avani tweets as @avani_kapur

)