The Kashmir Valley doesn’t have movie halls, but that hasn’t deterred locals from watching Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider widely on the Internet. Most of them have lauded it for being as close to the “real” Kashmir as Bollywood has ever dared to venture. “I downloaded it as soon as I could, and watched it with my friends. Some of them think it’s not enough, but I personally felt it is a brave movie,” says Nasir Lone, a journalist who is currently working with Goonj, an NGO, in Srinagar.

Nasir expects pirated DVDs to start circulating soon enough. The film’s popularity is explained by its authenticity — the handiwork of scriptwriter Basharat Peer, Kashmiri author and journalist who adapted William Shakespeare’s Hamlet to his hometown, Anantnag, in the Kashmir of the 1990s. Peer, inundated with congratulatory messages from friends, acquaintances and even strangers, is a happy man. What he is really elated about is that journalists who have covered the conflict in Kashmir appreciated Haider “as they knew exactly what each frame of the film referred to”.

Haider has borrowed many elements from Peer’s memoir, Curfewed Night, an account of growing up in conflict-ridden Kashmir. During the troubled 1990s when words like encounters, disappearances, half-widows, azadi and AFSPA [Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act] became common parlance for children in the Valley, Peer too, like the protagonist in Haider, was sent away by his parents to Aligarh Muslim University, where he studied political science and literature.

Curfewed Night—a frontline memoir of life, love and war in Kashmir

He later came to Delhi to study law, but quit to pursue journalism. It was then that he first decided to pen Kashmir’s stories. “...there was also a sense of shame that overcame me every time I walked into a bookstore. I felt the absence of our own telling, the unwritten books about the Kashmiri experience, from the bookshelves, as vividly as the absence of a beloved,” wrote Peer in Curfewed Night, a book that compelled Rekha Bhardwaj to bring it to her husband’s notice.

Currently based out of New York, I catch Peer over Skype on his way to Washington DC on a local train. While the train hoots away in the background, Peer shares anecdotes about all that has led up to Haider. His bureaucrat father was always a fan of Shakespeare and other canonical literature. “Bhardwaj emailed me about writing an adaptation set in Kashmir; he had either Hamlet or King Lear in mind but we both realised very quickly that Hamlet would be most apt. Hamlet’s story of the betrayal and oppression faced by a traumatised young man struggling to make difficult choices that he is not able to make resonated with the history of Kashmir,” he says.

A big fan of George Orwell, Charles Dickens and James Baldwin, Peer began to work on the first draft of the script by rereading Shakespeare’s original many times over, and taking inspiration from the scripts of other conflict films. Haider was a labour of love: during the day he was working as the editor of The New York Times’ India Ink blog; at night and on weekends, he was writing the script, working 16 to 18 hours a day. “Not that it felt like work,” he’s quick to add.

The process of production was a combination of Bhardwaj and Peer’s very different yet complementary sensibilities. Peer concedes that there will always be different ideas when two people work together and eventually it’s the director’s film and the outcome depends on how he visualises it.

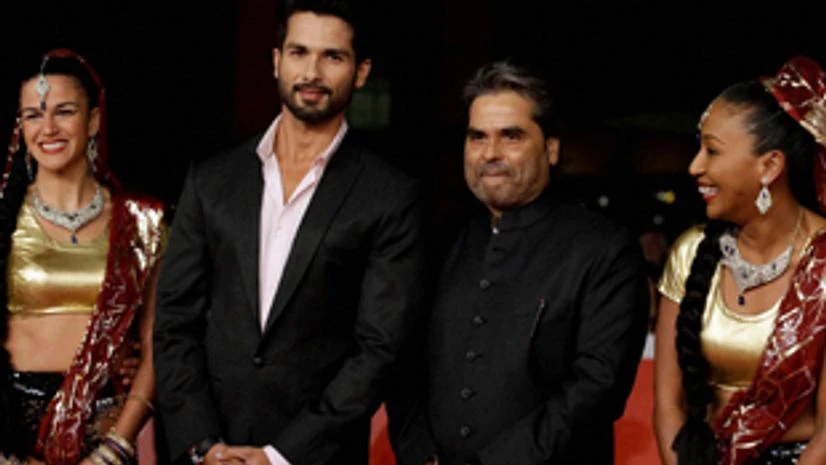

Actor Shahid Kapoor (second from left) and director Vishal Bhardwaj who adapted Shakespear's Hamlet for Haider

“I wrote it in a vein of the realist novel, that is why the first half of the film is very realist, and that’s when Bhardwaj the filmmaker would step in to point out nahi yaar, it’s becoming too documentary-ish, there should be a joke here, a song there. He knows the Mumbai grammar,” says Peer, who stayed on the film set for a fortnight.

He has a brief cameo in a powerful scene in the film, which was taken from Akhtar Mohiuddin’s short story, New Disease, in which he essays the role of a man who stops every time he comes to any doorway, refusing to proceed until he is asked for his ID and searched. It was Bhardwaj’s idea for him to play this part, prompting his friends to say: “Bollywood debut kiya bhi toh Irrfan ke saath kiya!”

His friends from his university days in Delhi have fond things to say about him. Referring to him as a people’s person, one friend calls him “a well-intentioned Salman Khan.” Peer is married to Ananya Vajpeyi, an academician and award-winning author of The Righteous Republic: The Political Foundations of Modern India. His friends affably call her his biggest fan.

And he has a life beyond Kashmir. “Looking at Haider, you may think he can only write high-brow intellectual stuff, but he's a great movie buff and is equally capable of writing potboilers,” quips a journalist friend in mock seriousness. A primarily non-fiction writer, Peer himself professes to have enjoyed Salman Khan's mindless Dabangg, but doesn’t think he can write “fantasy”.

Basharat Peer and Irrfan in a still from Haider

Also Read

Haider has just finished its fourth week in theatres, having sparked equal shares of conversations and controversy between traditionalists and fundamentalists alike. The weekend of the release saw a Twitter backlash, with #BoycottHaider trending in India. Peer says he was not surprised or afraid as he is used to this kind of abuse. He chose to be indifferent instead.

“Stories don’t work on a quota basis: you can’t have an equal representation of all castes, communities and religions. There are millions of stories that need to be told and efforts need to be made to tell them, this was just one such effort.” Peer envisions that in the future there will be more works that’ll push the boundaries.

Haider poster

His hopes are shared by a retired army officer who served in the Kashmir Valley between 1994 and 1997, writing for a news agency, “The movie captures many truths of that period. But it is not the complete truth...Let a thousand more Haiders bloom.” The hashtag, propounded by outraged army loyalists, didn’t last beyond a couple of days, and supporters of the film were able to get #HaiderTrueCinema trending soon enough.

While the film has been banned in Pakistan where the censors have deemed it “against the ideology of Pakistan,” it has been on the receiving end of a notice from the Allahabad High Court on the basis of a public interest litigation filed by the Hindu Front for Justice, a group of lawyers who are seeking a ban on the film on the grounds that it is against “national interest”. The respondents — the Central Board of Film Certification, co-producer Siddharth Roy Kapur, Bharadwaj and Peer — have until November 15 to reply, by which time Haider would effectively have completed its theatrical run. However, a proposed ban would mean a loss of TV rights, and an even lesser chance of viewing the film for most Kashmiris.

Still, Haider has done decent business. Made on a budget of Rs 22 crore, it has already crossed Rs 58 crore in box-office collections. Peer is now working on a non-fiction travelogue on religion and politics in South Asia. He isn’t ruling out scriptwriting in the future, though. “Film was a great experience, I learnt a new way of telling a story.”

)