Bhim sits in his taal and languidly flicks his tail to disperse pesky flies as he contentedly surveys the world around him. He is by far the most priviledged buffalo I know. This taal was created solely for him to loll in after he found himself with an injured hind leg at All Creatures Great And Small (ACGS).

Not far from him, Sita, one of the female buffalos, sits majestically in the sun dozing, done with her soaking for the day. Kamli, one of the blind female buffaloes is walking around restlessly. Two blind calves (there are six at ACGS) nearby are running in circles, something blind calves often tend to do all day, I learn to my utter surprise. If this all-day running around tires them out, they don’t let on in any way.

Bhim’s leg has healed since but he is now a member of the over 700-odd animal family housed here, over 100 of whom are blind, a few mute and deaf. George Orwell’s allegory comes alive before your eyes except rebellion is the farthest thought from the inhabitants mind. In fact, never have I seen so many creatures exist in such harmony and acceptance of each other’s peculiarities. Bhim, Kamli and Sita (who broke her leg when dragged by a dumper) belong to a world many humans including a few in our small group of five would kill for.

As we enter the premises, 150 or 200 hundred excited dogs surround and jump on each of us. It’s easy to mistake the animals friendliness for aggression but the problems are in your head, not theirs. The dogs want to be petted and fussed over. They return the favour with a generous lick whenever they can.

Bhim in his taal

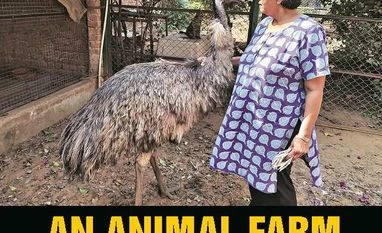

We are in Silakhari village in Faridabad district, around 30 kilometers from Delhi’s Qutub Minar at a unique 2.5 acre shelter home run by Naz foundation’s inimitable Anjali Gopalan, a leading social activist who set up Delhi’s first HIV center in 1994. The farm offers anyone who visits an alternate reality experience, a parallel universe anyone would desire a slice of.

The whole “mad” experiment started in 2012 when Gopalan came across an animal shelter in the capital and was appalled at the state of the animals it housed. The animals were scrawny, ill and uncared for, doing more of a disservice to the animals than acting as any kind of haven. That’s when she decided to set up what became ACGS, although she had her hands full with the Naz foundation and her shelter home for HIV infected individuals. Gopalan managed to buy 2.5 acres of land in Faridabad and decided to house any dogs who couldn’t survive outside due to old age, illness or injury. She began with 55 of them, rescued from the animal shelter she’d come across. The shelter now has 460 dogs in three large spaces. The dogs decide which space they primarily belong to. As time went on, many large animals were directed to the shelter and Gopalan and her team whose weakness is animals made space for every sort. Animals are not let out once healed since their ability to survive takes a hit after the kind of pampering they receive.

Duck pond

Even as we all gather our wits in the only space not overrun by animals, I watch in fascination as suddenly Mishti barges her way in through the widest and an absurdly high metal gap in a door that separates us from the other dogs. I learn she refuses to be separated from Gopalan for any time that the latter spends at the shelter, the only animal at the shelter permitted to enter every enclosure, an unquestioned exalted status. She has only three good legs but is a champion at high jump. She joined the ACGS family six years ago, found abandoned in a cardboard carton near a Delhi vet clinic.

Very soon I note that decibel levels at ACGS are on another plane : a runway may well be quieter. Every once in a way, a blind dog steps on the toes or disrupts the equilibrium of the pack. Yelps and long yowls break out and you think a war is on. In reality, it’s just a minor disagreement. There’s an annoying macaw that doesn’t stop squawking that I steadfastly resist from strangling many times through the day, aware my host may not appreciate it. I suggest they shift the bird closer to the periphery of the property to ensure they never have any neighbors, let alone complaining ones.

We begin our round of the shelter. Human empathy take on a new perspective at ACGS as one meets the 23-odd member staff dedicated to the facility, five of who live here and several who have been with it since inception. All animals have their own names and almost every staffer is intimately involved with the history of what brought each animal here. More than one of the staffers is from Siliguri, tracked down ACGS on social media and wrote to ask for a job. A 23 year old I meet is studying for his civil services entrance next May and can’t think of a better place to be. He finds being surrounded by the animals therapeutic and thrilling. Clearly, decibel levels are irrelevant to the young.

Enclosure with large animals at All Creatures Great and Small

Human cruelty too is at its starkest at ACGS as one learns how some animals found their way here and how many fail to survive the ordeals they faced. A young camel walked without rest, hydration and nourishment from Jaipur succumbed within a month of reaching ACGS. Kulhari is a mongrel whose scalp was visible when he came, so badly ruptured it was with a hammer, a wound that took five years to heal. There are at least 20 goats rescued from imminent slaughter, the most famous of them being Khan Chacha, a mountain goat with his long hair beard and equally long ears. Chiku is the only sheep, rescued from dissection for medical research. The list goes on and on.

After Gopalan has a conversation with the emus that ends in them smooching (yes, you read that right!), we pass Bhim (in his taal) and a bunch of cows, buffaloes and calves, all basking in the mild winter sun. The RSS brigade led by its chief should visit to leave with a warm, glowy feeling, I think to myself. Few cows would be as precious as the ones here.

We pass the duck pond (many of whom witnessed the Monty-Ponty Chaddha drama at their farm some years back) and turtles to reach the large animals enclosure and my stomach is knotty with fear. Everyone else in the group however follows the leader in without a care in the world. Bulls with impressive horns, donkeys, horses, a gigantic pig (almost unrecognisable to me on account of how squeaky clean and pink it is) all descend upon us to be loved and petted (apparently!), blissfully unaware of their own girth and human fears. I am petrified, embarrassed to admit it (fear seems sissy and awfully typical Indian) and stick uncomfortably close to Gopalan while trying my best to ward off the approaching…well what now look to me like beasts!

After a long, exhausting day that include a yummy lunch cooked by the local ladies who are employed on the premises with a fresh, plucked green salad, we head back to our car well after dark to leave, many reluctant to actually do so. Around two kilometers from the property however we come to a grinding halt to feed 300 chapatis to the stray dogs and monkeys – a daily ritual I learn - in the vicinity of the shelter, animals not fortunate enough to gain entry inside but “who need food regardless”.

As I bid goodbye to Gopalan and Co., I find myself saying a silent prayer. Let me, dear God, be born an animal in my next life unable to survive this big, bad world and somehow find my way to the paradise that is ACGS. Only a visit can help you understand why.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)