American chess genius Bobby Fischer and Soviet champion Boris Spassky are on stage in Reykjavik, Iceland, in 1972, but they are fighting several battles. The most obvious one is their tussle for the title of World Champion. Then there is the Cold War, with both players serving as proxies for their respective countries, the first time the mighty Soviet chess machine has been challenged by an American who has become a rock star but without the millions. The fiercest of all battles is raging within Fischer's head, as his paranoia and obvious mental illness collide with his burning ambition, keen sense of grievance and fury at anything in his way, including the soft whirr of a camera several feet behind him.

Director Edward Zwick builds up to this moment in Pawn Sacrifice by starting several moves ahead and getting his pieces into position, even if the manoeuvres, perhaps inevitably, don't match up to Fischer's brilliance. The face-off between Fischer and Spassky, dubbed the Match of the Century, which even managed to displace the Vietnam War and the Watergate break-in from the headlines at the time, forms the climax of this film, leaving the viewer with the high of having witnessed Fischer's first and only world title. Pawn Sacrifice premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 11.

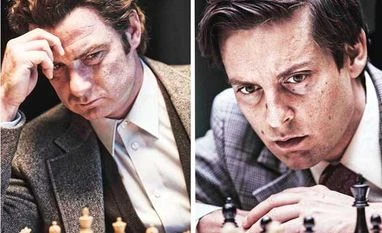

Spider-Man star Tobey Maguire, who plays Fischer and is also a producer for the film, delivers an intense performance, capturing the chess phenomenon's erratic ways and restlessness. Theatre star Liev Schreiber, recently seen in Mira Nair's The Reluctant Fundamentalist, is a debonair, somewhat un-Soviet Spassky, delivering most of his lines in Russian. Well-known actor Peter Sarsgaard plays the priest and chess Grandmaster Father Bill Lombardy, who is Fischer's chess second, and a supportive, calming presence around the tortured genius. Another key character is New York lawyer Paul Marshall, who had arranged deals for the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and volunteers to manage Fischer out of a sense of patriotism at the height of the Cold War.

Thrilled by his talent and brash declarations about beating the Russians and winning the world title, the Americans build up Fischer into an unlikely sports hero in a land obsessed with physical sports. But the adulation is not accompanied by the kind of money available to other sports heroes, a grievance that Fischer gives vent to often. He increasingly demands more money for his appearances, and for perks given automatically to other stars.

Even the Soviet Union treats its chess champions better, Fischer points out, when they send a team to Los Angeles. While the Russians are lodged in a luxury hotel, with attendants accompanying Spassky even to the beach to hold out his robe, Fischer is initially stuck in a dodgy motel. He walks out, and after some hard bargaining by Marshall, wins better lodgings. While in Los Angeles, he loses his match to Spassky and his virginity to a woman he meets at the motel.

Fischer famously forced the World Chess federation to change tournament rules after storming out of a tournament in 1962 and charging in a subsequent article in Sports Illustrated that the Russians were colluding to draw with each other and drop points to deny him victory. The film highlights all these episodes, sometimes focusing more on Fischer's complaints and demands than on his brilliant play. But the chess that's shown looks authentic, as there was a chess expert on the set. The crew even managed to track down the chessboards used by Fischer and Spassky in Reykjavik. Pawn Sacrifice also frequently uses the documentary treatment, with hand-held shots and footage treated to look grainy, but again, the style sometimes distracts from the substance of the story.

The tension within and around Fischer is always palpable, like a bomb that could go off any minute - and often does. Fischer refuses to get on the plane to Reykjavik unless his demands are met. Among his cajolers are US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger who calls personally. Once in Reykjavik, with his mind unravelling - we see the player take apart the telephones and smash fittings in his room -, his demands grow more outrageous. He wants the play moved to a rec room, while the audience watches the game on a screen. Apparently his illness is infectious, as Spassky gets into the game, complaining about a vibration from his chair. Were Fischer's eccentric ways a ploy to unsettle Spassky? And was Spassky faking his paranoia to counter what he believed were Fischer's mind games? In the end, blindsided and stunned by Fischer's unexpected and unprecedented moves, Spassky is gracious enough to applaud the new champion.

The film ends on this note, informing us through slides of the darker end to Fischer's real story. He refused to defend his title, and as his rants grew increasingly anti-American, his US passport was revoked. He was eventually given asylum and citizenship in Iceland, the place of his greatest triumph. He died there in January 2008, aged 64.

For the casual follower, chess is not an easy sport to watch on stage or on film. Fischer converted a whole nation, and much of the world, by the sheer force of his personality. In India, that honour goes to five-time world champion Viswanathan Anand whose calm, good humoured appearance couldn't be more at odds with Fischer's frenzy. But on the board with 64 squares, they are all playing the same game, black versus white, ready to sacrifice a pawn to take out the king.

Director Edward Zwick builds up to this moment in Pawn Sacrifice by starting several moves ahead and getting his pieces into position, even if the manoeuvres, perhaps inevitably, don't match up to Fischer's brilliance. The face-off between Fischer and Spassky, dubbed the Match of the Century, which even managed to displace the Vietnam War and the Watergate break-in from the headlines at the time, forms the climax of this film, leaving the viewer with the high of having witnessed Fischer's first and only world title. Pawn Sacrifice premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival on September 11.

Spider-Man star Tobey Maguire, who plays Fischer and is also a producer for the film, delivers an intense performance, capturing the chess phenomenon's erratic ways and restlessness. Theatre star Liev Schreiber, recently seen in Mira Nair's The Reluctant Fundamentalist, is a debonair, somewhat un-Soviet Spassky, delivering most of his lines in Russian. Well-known actor Peter Sarsgaard plays the priest and chess Grandmaster Father Bill Lombardy, who is Fischer's chess second, and a supportive, calming presence around the tortured genius. Another key character is New York lawyer Paul Marshall, who had arranged deals for the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and volunteers to manage Fischer out of a sense of patriotism at the height of the Cold War.

Also Read

The film follows Fischer from his childhood in Brooklyn, New York. His resentment against his mother, a Jewish communist activist, for her dalliances with men and for refusing to identify his real father, may have sowed the seeds of Fischer's intense hatred and suspicion of the Russians in his later years. Even as he wins every chess tournament in sight and is hailed as a child prodigy, Fischer is estranged from his mother, letting only his half-sister, Joan, into his life. It is Joan who first voices concern about his mental condition to Marshall, disturbed by the paranoid ramblings and anti-Semitism in the letters from her brother. "We're Jewish," she points out to the lawyer.

Thrilled by his talent and brash declarations about beating the Russians and winning the world title, the Americans build up Fischer into an unlikely sports hero in a land obsessed with physical sports. But the adulation is not accompanied by the kind of money available to other sports heroes, a grievance that Fischer gives vent to often. He increasingly demands more money for his appearances, and for perks given automatically to other stars.

Even the Soviet Union treats its chess champions better, Fischer points out, when they send a team to Los Angeles. While the Russians are lodged in a luxury hotel, with attendants accompanying Spassky even to the beach to hold out his robe, Fischer is initially stuck in a dodgy motel. He walks out, and after some hard bargaining by Marshall, wins better lodgings. While in Los Angeles, he loses his match to Spassky and his virginity to a woman he meets at the motel.

Fischer famously forced the World Chess federation to change tournament rules after storming out of a tournament in 1962 and charging in a subsequent article in Sports Illustrated that the Russians were colluding to draw with each other and drop points to deny him victory. The film highlights all these episodes, sometimes focusing more on Fischer's complaints and demands than on his brilliant play. But the chess that's shown looks authentic, as there was a chess expert on the set. The crew even managed to track down the chessboards used by Fischer and Spassky in Reykjavik. Pawn Sacrifice also frequently uses the documentary treatment, with hand-held shots and footage treated to look grainy, but again, the style sometimes distracts from the substance of the story.

The tension within and around Fischer is always palpable, like a bomb that could go off any minute - and often does. Fischer refuses to get on the plane to Reykjavik unless his demands are met. Among his cajolers are US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger who calls personally. Once in Reykjavik, with his mind unravelling - we see the player take apart the telephones and smash fittings in his room -, his demands grow more outrageous. He wants the play moved to a rec room, while the audience watches the game on a screen. Apparently his illness is infectious, as Spassky gets into the game, complaining about a vibration from his chair. Were Fischer's eccentric ways a ploy to unsettle Spassky? And was Spassky faking his paranoia to counter what he believed were Fischer's mind games? In the end, blindsided and stunned by Fischer's unexpected and unprecedented moves, Spassky is gracious enough to applaud the new champion.

The film ends on this note, informing us through slides of the darker end to Fischer's real story. He refused to defend his title, and as his rants grew increasingly anti-American, his US passport was revoked. He was eventually given asylum and citizenship in Iceland, the place of his greatest triumph. He died there in January 2008, aged 64.

For the casual follower, chess is not an easy sport to watch on stage or on film. Fischer converted a whole nation, and much of the world, by the sheer force of his personality. In India, that honour goes to five-time world champion Viswanathan Anand whose calm, good humoured appearance couldn't be more at odds with Fischer's frenzy. But on the board with 64 squares, they are all playing the same game, black versus white, ready to sacrifice a pawn to take out the king.

)