Once there, I walked around in desultory fashion to take in the city: the Pantheon, the Colosseum and the arches and, of course, the Palatine hill. Italy is full of young Bangladeshi men, similar looking: thin, dark and short, spirited and full of hustle. The recent arrivals were selling iced water and selfie sticks; the ones more settled in were waiters, chefs and managers of street stalls. It was pleasant to chat with them, in my broken and Maganlal Meghraj-accented Bangla, and to hear their stories and tell them mine. They are everywhere: a couple of years ago my wife and I travelled across Italy, needing to speak nothing other than Bengali.

This time, having walked through much of Rome (it is very small and unchanged over the centuries, which is why it’s called the eternal city) on my first trip into town, I consulted the map to see what to do for trip two. I noticed I hadn’t been to the Spanish Steps, where a church sits on top of an unusually grand stone stairway large enough to seat a thousand people. As I approached it, around 11.30 am, I saw standing in one corner of the square, just off the pavement, a woman singing.

She was a middle-aged soprano and she held herself in formal fashion, with pride. She sang looking up into the middle distance, wearing a velvet gown (it was horridly warm), her bust thrust out, and with make-up on. She was singing something I knew: Charles Gounoud’s “Ave Maria”. She was excellent: unhurried and effortless. A man sat a few feet to her left, playing in accompaniment. His keyboard was amplified through a small portable speaker, but her singing was not.

She sang naturally, projecting out. Her voice cut clean through the air, filling up the square. The open case inviting contributions and support had a few dozen coins, perhaps ^40 or so. I tossed in a coin and listened for a while by the side. When it ended, a few of us applauded and she acknowledged us with smiles and blown kisses.

I think the tradition of busking, which is what street performance of music is called, is one of the most civilised things in the world. The word busker means an itinerant entertainer. What struck me when I first saw one, on my first visit to the United States 30 years ago, was how high the quality of the musicianship was. I was playing with a band in those years and so I knew a thing or two about music. What I was hearing was far ahead of anything I had heard live from young musicians before.

On my first visit to London I saw remarkably talented buskers in the Tube station stairwells and in public places. By that time, this was a couple of decades ago, they were being regulated by the civic authorities, checked for quality and diversity and then given specific, marked spaces for a couple of hours of busking.

Let’s return to Rome where, sitting halfway up the Spanish Steps in the shade to consult the map, I could still hear the soprano, now 150 metres away. This would not of course be possible in the centre of an Indian city. For one, the accompaniment of honking and other forms of desi chaos would drown out the performer.

For another, we may have quality musicians but on the street they would not be practising their art and their trade but primarily be reduced to begging. The 40 euros that the soprano and her companion made (a little more than Rs 3,000) was probably par for a couple of hours’ work, and not much, but it came with magnificent perks: independence and freedom.

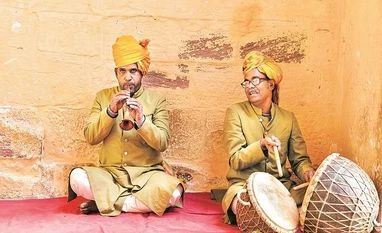

This dignity of the European busker is absent in our parts and this is not the fault of the Indian musician. We have many flaws as a society but one thing we can be justifiably proud of is the quality of our music. It is gorgeous and many of its traditional performers first rate. My wife says she was at Fatehpur Sikri one deserted afternoon. She was entertained by a solo qawwal who sang to mesmerise, as qawwals are wont to do, and played the harmonium. She had no money to give him, but he insisted she listen to another piece just the same. He must have liked performing.

Karl Marx said about the modern work culture, where each of us made a vague contribution to a giant machine, that it alienated us. But what if we were independent, individual producers of goods and services? Then “each of us would have, in two ways, affirmed himself, and the other person. (i) In my production I would have objectified my individuality, its specific character, and, therefore, enjoyed not only an individual manifestation of my life during the activity, but also, when looking at the object, I would have the individual pleasure of knowing my personality to be objective, visible to the senses, and, hence, a power beyond all doubt. (ii) In your enjoyment, or use, of my product I would have the direct enjoyment both of being conscious of having satisfied a human need by my work, that is, of having objectified man’s essential nature, and of having thus created an object corresponding to the need of another man’s essential nature.”

Replace here the word object with music and we know how the busker feels and why she does what she does. The alienation is true for the occupant of the cubicle but not the cobbler or the carpenter, the musician or, indeed, the columnist.

I wish we can introduce the culture of busking in our cities: in our Metro stations, in our soulless malls, if not on the streets. It would make our cities better, more civilised and more humane.

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)