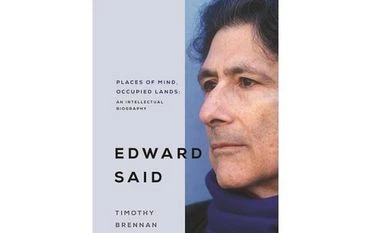

Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said

Author: Timothy Brennan

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, London, 2021

Pages: 437

Price: Rs 1099

In an intellectual scenario dominated by western thinkers, Edward Said (1935-2003) stands out as a remarkable exception — of Palestinian Arab origin, he towered as a literary critic and political philosopher in the US’ most important Ivy League institutions. He was also a political activist and a powerful voice in support of the Palestinian struggle, at a time when US political, academic and media circles were robustly pro-Israel and actively hostile to Arabs, Muslims and Palestinians.

He combined these two aspects of his persona in writing two of the most influential books of the twentieth century — Orientalism and Culture and Imperialism — that challenged time-honoured western cultural perceptions of the “Orient” and exposed threadbare the assumptions, prejudices and atrocities that have shaped the West’s encounter with the East over the last few centuries.

This book is not a conventional biography; it is an intellectual history that explores the diverse influences that shaped Said’s thinking, his deep intellectual engagement with western writers and philosophers, past and contemporary, and how he attempted to balance in his life his roles as thinker, writer and teacher and as an active votary of the Palestinian cause.

Coming from an affluent, even privileged, background and an American citizen from birth, Said was a student at Princeton and Harvard and taught English Literature at Columbia. The early part of this book shows Said gradually placing himself at the centre of the debates in American academia on literary theory and the impact on these discussions of European thinkers such as Foucault, Sartre, Derrida and Claude Levi-Strauss. Said and his colleagues, most of them polarised between left and right, vigorously debated among themselves language, grammar, semantics, meaning and creativity.

By 1968, Said was accepted in the US and Europe as the “face of Continental theory”. At the same time, Said’s political awareness, nurtured within his family from childhood, sharpened after the 1967 debacle for the Arabs. But it was the Pakistani-origin Marxist intellectual and activist, Eqbal Ahmad who instilled in him the zeal of an intellectual revolutionary. Said even addressed students at Columbia protesting about the Vietnam war on the Palestine issue.

Orientalism, published in 1978, sealed Said’s global reputation as a powerful voice against imperialism. In his introduction, Said described the Orient for the European as “one of its deepest and most recurring images of the Other”, one that defined the West “as its contrasting image, idea, personality, and experience”. In a separate note, Said pointed out that this definition was of “the official culture itself, not just media distortions”.

Even as it gathered a cult-following across the world, the book was attacked from the left and right. The former questioned Said’s qualifications, his absence of specialist knowledge of West Asia and what some saw as “gratuitous jibes at Marx”.

Right-wing critics were particularly vicious – Said had referred in the book to some of their stalwarts – Bernard Lewis, Fouad Ajami and Daniel Pipes – whom Mr Brennan describes as “modern descendants of the racialised scholarship his book had set out to expose”. But Orientalism made “Post-Colonial Studies” an essential part of university curricula, bringing non-western writers to university libraries and classrooms, though Said denied that a post-colonial era had emerged as yet!

Culture and Imperialism, published in 1993, complements Orientalism – it examines “a more general pattern of relationships” between the West and its overseas territories and also focuses on the cultural and political resistance that led to decolonisation in different parts of the world.

These important intellectual contributions sat side-by-side with Said’s active role for the Palestinian cause – but here the intellectual clashed with political reality. Said helped write Yasser Arafat’s historic speech at the UN General Assembly on 3 November 1974 and then over the next three decades wrote several essays and articles on the Palestine issue for US and Arab media.

FBI reports of the period carefully analysed his writings and concluded that they were “dangerous, especially to Israel, and would become more so”. In an unintended vindication of Said’s writings and political activism, a right-wing scholar testified before a Congressional subcommittee in 2003 that Said’s postcolonial critique had left US scholars “impotent to contribute to Bush’s ‘war on terror’.”

Said was soon disenchanted by the Palestinian leadership and became a harsh critic of the Oslo Accords. He presciently noted that, with the principal claims of the Palestinians relating to sovereignty, settlements, Jerusalem and right of return of refugees deferred to future discussions, Oslo marked “the end of the peace process”.

This book does not tell us much about Edward Said the human being: we find scattered remarks across the book of a “compassionate but fiery” person, a man “capacious and alert, a little daunting, and often very funny”. The author speaks of a “fair amount of bad behaviour – the vanity, the occasional petulance, the need for constant love and affirmation”. The author also quotes Said’s friend describing him as “tempestuous, forceful, uncompromisingly outspoken … relentless restless, theatrical and always very funny”.

For an intellectual history, there are some important omissions – Mr Brennan fails to mention Said’s response to Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilisations. Again, while he describes Salman Rushdie as Said’s “good friend”, we are not told how Said reacted to The Satanic Verses or to Khomeini’s death sentence on the writer. Nor does Mr Brennan tell us why Said was hostile to his parents in his memoir, Out of Place, though we had been told earlier that he was “obsessive” about his mother.

Edward Said’s enduring legacy is the change he brought about in western academia – as Mr Brennan notes, “anti-imperialism was the new common sense … and the force of culture in political struggle an acceptable version of the facts”. In his last days, as Said was melancholic, a friend told him: “I don’t know what you are fighting about … You’ve won.”

(The reviewer is a former diplomat.)

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)