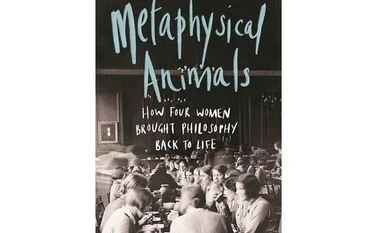

Clare Mac Cumhaill, an associate professor of philosophy at Durham University, and Rachael Wiseman, a lecturer at the University of Liverpool, recount the history of this remarkable friendship in Metaphysical Animals: How Four Women Brought Philosophy Back to Life — the second of two books about the quartet (after Benjamin J B Lipscomb’s The Women Are Up to Something) to be published in less than a year. In the chapter on the tearoom gathering, it explains Foot’s insight about the word “rude,” which is most certainly employed in value statements, but also, Foot pointed out, can’t be applied to just any action, such as “walking up to a front door slowly or sitting on a pile of hay.” “Rudeness” — for example, simply walking away from a person offering a friendly greeting — refers to the violation of a shared norm of a human community: It is polite to acknowledge and return such greetings. Human beings will instantly recognise that rudeness as a fact, even if it has no material existence and isn’t inherent in the act of walking away.

The least well-known of the four friends, Midgley survived the longest. She died at the age of 99 in 2018, an influential figure in the area of animal rights, but not before writing a letter to The Guardian in which she asserted that women philosophers flourished in Oxford during and just after World War II because “there were fewer men about then.” Furthermore, she added, the women’s style of philosophizing was less aggressive and competitive, and also less likely to degenerate into a “set of games” built “out of simple oppositions.” Mac Cumhaill and Wiseman write that the interviews they conducted with Midgley at the retirement home where she lived became the springboard for the book.

As this origin story suggests, the heart of this book resides in the friendship among the four women and the ways they supported and influenced one another. Anscombe, the most brilliant and gifted philosopher of the group, was a protégée and friend of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Married to a conscientious objector who had difficulty finding remunerative work after the war, Anscombe was so poor that Wittgenstein paid for her stay in a maternity hospital after the birth of her second child and insisted on furnishing her spartan lodgings. Many people did find Anscombe rude, especially the university authorities who objected to her delivering lectures in trousers instead of the required skirts.

Foot, who would become Murdoch’s “lifelong best friend,” endured a loveless upper-class childhood in a milieu where one of the worst things a woman could do was appear intelligent. She would go on to become a professor of philosophy at UCLA and is considered one of the inventors of the “trolley problem,” a thought experiment that poses the question of whether it is ethical to deliberately sacrifice one person’s life to prevent the accidental deaths of five others.

During the time when they were both employed in the war effort, Foot and Murdoch shared a peculiar but beloved attic flat near Whitehall. It had no running water in the kitchen, and became even less comfortable when each woman took up with one of the other’s ex-lovers, a situation, the authors note, providing Murdoch with “the archetype of a tangled erotic muddle for her novels.”

The biographical material in Metaphysical Animals is evocative and sparkling. What’s less persuasive is the book’s overall thesis that the four friends somehow redirected the course of British philosophy or even that they shared a distinct cause or approach. Anscombe, for example, was a committed Catholic who opposed both birth control and abortion. Foot was an atheist who told Anscombe that she saw no good reason to believe otherwise. Murdoch was drawn to existentialism and published the first English-language book on Sartre. Midgley became increasingly interested in the similarities between human beings and animals. Many of the ideas touched on are too challenging to summarize in a book with so many other balls in the air. The four unconventional friends are delightful enough company that their story doesn’t require the “How X changed the world” overlay. To impose that theme on their story is to reduce it to one of those “simple oppositions” that Midgley herself complained about, a form that could never do justice to these four fascinating women.

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)