Like Veda’s mother, we probably don’t think about it either — this daily othering, this differentiation between “us” and “them”. And had it not been for the story of the tea cups, told inside an air-conditioned car one summer afternoon in April 2015, Veda too would not have thought about it, let alone confess to it. On that afternoon, when she was on her way to schools in Ahmedabad and Surendranagar, her travelling companion, 55-year-old Martin Macwan, a Dalit human rights activist who founded the Navsarjan Trust in 1988, first mentions the tea cups. In 1977, a 17-year-old Macwan begins an investigation of the lives of Dalits in the village of Vainaj in Gujarat, together with his professors from the Behavioural Science Centre of St Xavier’s College, Ahmedabad. He notices a cup and saucer lying outside every home in the village, placed either on a wooden pillar or upon a courtyard fence. “The village was like a veritable museum of tea cups!” Macwan tells Veda.

The cups, or Rampatars, as Martin discovers they are called, are utensils that are kept aside by the upper castes for Dalit labourers to drink tea or water from, after they have completed the task for which they have been summoned. “But it took me 25 long years to fully comprehend the role of the Rampatar and to break its symbolism,” Macwan tells Veda, as they drive towards a new expedition into the unforgiving topography of caste in India.

The Museum of Broken Tea Cups is an edifice of fortitude, a magnificent structure of sunlit stories from dingy corners of the country. To break the metaphorical tea cup is to break free from the confines of one’s caste and its predestined lot: poverty, humiliation and disenfranchisement. The story of each smashed tea cup is chronicled upon a postcard with the photograph of the individual or group that has been documented, as well as the district and state to which they belong.

Veda uses the term “cultural philanthropists” to describe the Dalit artistes she meets. Splendid in their craft, they often face fierce resistance from the upper castes in pursuing the arts. Shatrughan, for instance, had to struggle to weave the famed Sambalpuri Ikat sari, which was brought into western Odisha by the Bhulia community in 1192 AD. “We were regarded as untouchables. Who would teach us,” he asks Veda, rhetorically. He eventually does learn to weave the Sambalpuri Ikat sari, an act that amplifies the metaphorical breaking of the tea cups.

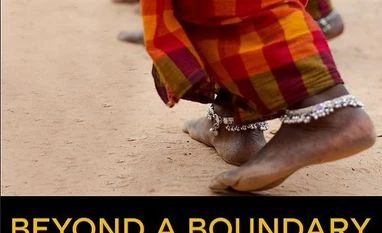

The book, then, is a celebration of defiance. It is boisterous applause to the music of the Ganda Bajaa troupes — the offensive nomenclature (ganda means foul smelling) an indicator of their instruments made of cowhide, and the act of touching their own saliva while playing the mohuri. It is ecstatic dancing to the ballads of the Dewar group of nomads.

But The Museum of Broken Tea Cups is also a sobering interrogation. For instance, it wants to know why the girls of the leather-working Madiga community of Telangana are still dedicated to temple services, married to Goddess Yellamma at the age of 10 or 11 and made to lead the life of a jogini, a euphemism for sex worker. It also questions us, albeit gently, about the chipped tea cups in our own homes, set aside for the help. Veda has already acknowledged her own biases. Now she urges us to do the same, at least to ourselves.

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)