"Doctor, have you tried marijuana?"

"No"

"Then how do you know it is bad?"

Brahmdeep Sindhu, senior psychiatrist at the Civil Hospital in Gurgaon, was stumped when a 14-year-old from a prominent school threw this question at him. "The child then went to great lengths, quoting blogs he had read on the internet, to convince me why he, many of his classmates and some of his juniors, children as young as 12, thought it was harmless, even beneficial, to smoke up."

Every month, 15 to 20 new cases of schoolchildren, boys and girls, are brought by their parents to Sindhu for counselling. They are all hooked to cannabis: often marijuana (the leaf of the plant) and sometimes hashish (extracted from the plant's resin).

Far away from Gurgaon, in the fields past Navi Mumbai, children, in school uniform, can occasionally be seen purchasing weed that is grown here, hidden from the authorities by the other crop growing around it. With prices as low as Rs 50 to Rs 100 a pop, it is hardly out of reach for these kids.

In Bengaluru, Gambetta da Costa, co-founder of drug and alcohol rehabilitation centre Higher Power Foundation, is dealing with an unprecedented number of 10- to 16-year-olds who are doing cannabis and party drugs. "We take in 25 people at the most. Today, at least 10 of them, or 40 per cent, are children from primary and high school," he says.

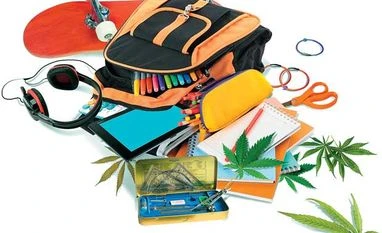

The harsh reality is that an increasing number of boys and girls, some as young as 11, are experimenting with cannabis which also goes by names like weed, pot, grass, herb and boom. Medicinal drugs and smelling agents like whiteners and nail paint removers that give a high are losing out to marijuana.

More than parents, schoolteachers and classmates are the ones to notice the changes first that take place in a child high on marijuana. "A perfectly normal child will suddenly stop caring about his appearance, his eyes will be red and his expression aloof," says Laxmi Prasad Jaiswal, senior counsellor at Yuva, a toll-free helpline run by the Delhi government for students, parents and teachers. He puts the age of initiation into marijuana at as low as 9.

Teachers have observed children addicted to marijuana dropping out of sports and their friends' circle changing. "It's like they are in some kind of a zone, a world of their own, instantly happy or totally distracted," says Swati Marwah, a college student many of whose schoolmates had started smoking weed by the time they were in Class IX or X.

This is dangerous: marijuana impairs the person's cognitive abilities and its long-term use damages the brain irreversibly. Most children start with the belief that they can opt out anytime, which is easier said than done.

The argument that children most often present in support of cannabis is that it is not a drug. "How can something that comes from a plant and is organic be a drug?" says a 15-year-old. "Would responsible adults have it if it were harmful?" His reference is to bhang, another form of cannabis, which will be consumed in copious amounts in households next week on Holi.

Other arguments in their arsenal, thanks to the internet, include the old assertion that every year more people die from alcohol than cannabis, and that marijuana is legal in some parts of the US.

"What children don't realise is that marijuana is a gateway drug. It's the doorway to higher, stronger and more dangerous drugs," says Suneel Vatsyayan, psychotherapist and director of Delhi-based Nada India Foundation that works on child-related issues. A child hooked to marijuana will eventually get bored of its subtle effects and will want to move to something harder like cocaine or heroin.

Vijay Simha, an independent therapist in Delhi, is dealing with one such case: a 19-year-old heroin addict who started with marijuana when he was in Class VII. Now, while he is getting weaned away from heroin, he still smokes a joint of marijuana every night before going to sleep. "'Marijuana to nasha hi nahin hai (marijuana isn't a drug),' he tells me," says Simha.

With demand surging, dope adulterated with chemicals, pesticides and even shoe polish is being supplied to children. It is far more dangerous and way more addictive. As a result, "signs of marijuana psychosis, delusion and paranoia start manifesting much earlier," says Indrajeet Deshmukh, founder of Pune-based de-addiction centre Practical Life Skills.

For something like marijuana to hit off with children this young, two factors are critical: access and acceptability.

Earlier, every city would have a corner or two where intoxicants were sold. Today, an army of peddlers - school cabbies, auto-rickshaw drivers, paanwallas or washmen -brings the drug to the child.

"It's a joke how easily marijuana is available," says Gurgaon-based wellness consultant Ruchi Puri, a doctor who conducts workshops for parents whose children are in the receptive age for drugs. The child has access to it on his way to tuitions; it is often available in the corner market or at the paan or cigarette shop.

Law forbids cigarette and tobacco kiosks within 100 metres of a school. Indeed, these kiosks are gone but children point to cobblers, tea makers and even papad vendors adjacent to their school who they say sell drugs.

Jaiswal of Yuva has seen ganja and afeem being sold within the prohibited 100-metre radius of schools. He says when a school counsellor got a whiff that a vendor was selling them to children she confronted him, but was threatened and told to mind her own business. Dealers stay in touch with kids on WhatsApp. Some stuff is available online too.

Most counsellors argue that the trade cannot flourish without the knowledge of the police. The police counter that the network is so widespread and pervasive that it's tough to tell who might be supplying the cannabis to children. "We have cracked down on medicinal intoxicants and the abuse of those has gone down drastically," says Amandeep Chauhan, drug control officer, Gurgaon.

But the same cannot be said for dry intoxicants like bhang, afeem, marijuana and hashish. In Solapur, cannabis fields were recently burnt by the authorities but it is difficult to keep track of the dozens of new fields that have cropped up.

As compared to cocaine and heroin, weed and hashish are much easier on the pocket. The weekly pocket money is enough to pay for it.

The Bhola goli, a form of bhang, can cost as little as Rs 2 to Rs 5. A packet of weed costs Rs 100 to Rs 200 and is enough for rolling four or five joints. And with 10 gm of hashish, which is purer and costs Rs 1,200 to Rs 1,500, a child can roll 10-15 joints.

For girls, who might hesitate to smoke up, there is the marijuana-laced paste. "They rub it on their gums and it gets absorbed into the blood stream," says Sindhu from the Gurgaon Civil Hospital. "It smells like mouth freshener, so the girls find it safe."

As dependence increases, so does the need for more pocket money. But not all parents oblige. It's normal then for the child to resort to stealing. Beside, after the initial free packets to get the child hooked, the dealer also starts charging more for the dope because he knows the child will not rattle.

Almost every child, age nine and above, today has a mobile phone, says Sindhu. "He sells the phone, tells his parents it got stolen or was lost and then the parents buy him a new phone," he says. So now the child has both money and a new phone. Other things also start disappearing from the house: expensive video games, watches, wallets and even the father's branded shirts.

A safe locker to store valuables has become a must even in nuclear households.

Peer pressure, the need to fit into the group and "be cool" are the key reasons children say they start smoking up.

"The breakdown of the joint family structure, nuclear units with both working parents where the child is left unsupervised for several hours, have removed stability from children's lives," says Puri, the wellness consultant. Parents, exhausted from the day at work, will let a child go to a friend's place even late in the evening. "There is a good chance that the friend's parents too would be out and the children are alone again to do what they please."

Children then start relying more on friends and the internet for company, from where they often get misguided information about things, including marijuana.

They may also inadvertently see older people rolling a joint at a party. The reality is that while marijuana is illegal, it is socially acceptable. Many children are aware that their parents do smoke up (however discreet the parents think they are being, the kids are just that much smarter), says Puri. "Or they have heard stories from their uncles or aunts of the time their parents smoked up when they were younger."

A spin-off is the resurrection of Bob Marley, the high priest of ganja, in popular culture. At Janpath, Delhi's popular flea market, Marley accessories and T-shirts are a huge rage, even amongst kids, so much so that at some shops they are nearly sold out. Then there T-shirts with direct messages like: "Dude! Got Joint?" or "Tu weed badi hai mast mast - Pure Veg".

Parents are often at a loss about what to do on discovering that their child is smoking pot. The first reaction often is denial and then they pass the blame - on friends, teachers and the school. Some choose to change their ward's school on learning that he was smoking up.

Guilt is another reaction. Madhulika Anand, a Delhi-based doctor, has taken a break from work after she found weed in her 15-year-old son's school uniform. "You can say I have put my life on hold," she says.

Sindhu, the Gurgaon psychiatrist, calls it "annihilation anxiety - when you feel the world has come to an end". He knows of parents who have gone into depression and those who have taken child care leave for a year. "Among them are people whose careers call for continuity, like lawyers, doctors and architects. When they eventually get back to work, they will have to rebuild their careers from scratch," he says.

Rarely, but sometimes, desperate parents also turn to detectives. "On an average, two or three parents come to us every month after they notice a drastic change in their child's behaviour or appearance but are unable to draw a satisfactory explanation out of him or her," says Bhavna Paliwal, the founder of Delhi-based Tejas Detective Agency. "They suspect the child is doing drugs."

In some cases, their suspicion turns out to be true.

Some names have been changed on request;

Ranjita Ganesan in Mumbai, Nikita Puri in Bengaluru and Avishek Rakshit in Kolkata contributed to this report

"No"

"Then how do you know it is bad?"

Brahmdeep Sindhu, senior psychiatrist at the Civil Hospital in Gurgaon, was stumped when a 14-year-old from a prominent school threw this question at him. "The child then went to great lengths, quoting blogs he had read on the internet, to convince me why he, many of his classmates and some of his juniors, children as young as 12, thought it was harmless, even beneficial, to smoke up."

Every month, 15 to 20 new cases of schoolchildren, boys and girls, are brought by their parents to Sindhu for counselling. They are all hooked to cannabis: often marijuana (the leaf of the plant) and sometimes hashish (extracted from the plant's resin).

Far away from Gurgaon, in the fields past Navi Mumbai, children, in school uniform, can occasionally be seen purchasing weed that is grown here, hidden from the authorities by the other crop growing around it. With prices as low as Rs 50 to Rs 100 a pop, it is hardly out of reach for these kids.

In Bengaluru, Gambetta da Costa, co-founder of drug and alcohol rehabilitation centre Higher Power Foundation, is dealing with an unprecedented number of 10- to 16-year-olds who are doing cannabis and party drugs. "We take in 25 people at the most. Today, at least 10 of them, or 40 per cent, are children from primary and high school," he says.

The harsh reality is that an increasing number of boys and girls, some as young as 11, are experimenting with cannabis which also goes by names like weed, pot, grass, herb and boom. Medicinal drugs and smelling agents like whiteners and nail paint removers that give a high are losing out to marijuana.

More than parents, schoolteachers and classmates are the ones to notice the changes first that take place in a child high on marijuana. "A perfectly normal child will suddenly stop caring about his appearance, his eyes will be red and his expression aloof," says Laxmi Prasad Jaiswal, senior counsellor at Yuva, a toll-free helpline run by the Delhi government for students, parents and teachers. He puts the age of initiation into marijuana at as low as 9.

Teachers have observed children addicted to marijuana dropping out of sports and their friends' circle changing. "It's like they are in some kind of a zone, a world of their own, instantly happy or totally distracted," says Swati Marwah, a college student many of whose schoolmates had started smoking weed by the time they were in Class IX or X.

This is dangerous: marijuana impairs the person's cognitive abilities and its long-term use damages the brain irreversibly. Most children start with the belief that they can opt out anytime, which is easier said than done.

The argument that children most often present in support of cannabis is that it is not a drug. "How can something that comes from a plant and is organic be a drug?" says a 15-year-old. "Would responsible adults have it if it were harmful?" His reference is to bhang, another form of cannabis, which will be consumed in copious amounts in households next week on Holi.

Other arguments in their arsenal, thanks to the internet, include the old assertion that every year more people die from alcohol than cannabis, and that marijuana is legal in some parts of the US.

| THE CANNABIS TRAIL |

| INDIA IS AWASH IN WEED It is cultivated across states — Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, West Bengal, Odisha, Punjab, Bihar, Jharkhand. FROM THE FIELDS TO THE METROS It is transported every day, both by train and road (often hidden in buses or in fruit and vegetable trucks). It comes in different forms — marijuana (from the leaf of the plant) or hashish (extracted from the resin of the plant). INSIDE THE CITY Touts, often on motorbikes, ferry the dope either to construction sites or migrant colonies where it is sifted and put into small packets. Sometimes tea kiosks in the area double up as packaging centres. THE LAST LEG Autorickshaw and cab drivers, dhobis in the locality, cigarette kiosks that also stock sweets for kids, the papad vendor, the seemingly innocuous tea-seller, the local chemist — an army of small-time dealers carry the drug to the children. |

"What children don't realise is that marijuana is a gateway drug. It's the doorway to higher, stronger and more dangerous drugs," says Suneel Vatsyayan, psychotherapist and director of Delhi-based Nada India Foundation that works on child-related issues. A child hooked to marijuana will eventually get bored of its subtle effects and will want to move to something harder like cocaine or heroin.

Vijay Simha, an independent therapist in Delhi, is dealing with one such case: a 19-year-old heroin addict who started with marijuana when he was in Class VII. Now, while he is getting weaned away from heroin, he still smokes a joint of marijuana every night before going to sleep. "'Marijuana to nasha hi nahin hai (marijuana isn't a drug),' he tells me," says Simha.

With demand surging, dope adulterated with chemicals, pesticides and even shoe polish is being supplied to children. It is far more dangerous and way more addictive. As a result, "signs of marijuana psychosis, delusion and paranoia start manifesting much earlier," says Indrajeet Deshmukh, founder of Pune-based de-addiction centre Practical Life Skills.

For something like marijuana to hit off with children this young, two factors are critical: access and acceptability.

Earlier, every city would have a corner or two where intoxicants were sold. Today, an army of peddlers - school cabbies, auto-rickshaw drivers, paanwallas or washmen -brings the drug to the child.

"It's a joke how easily marijuana is available," says Gurgaon-based wellness consultant Ruchi Puri, a doctor who conducts workshops for parents whose children are in the receptive age for drugs. The child has access to it on his way to tuitions; it is often available in the corner market or at the paan or cigarette shop.

Law forbids cigarette and tobacco kiosks within 100 metres of a school. Indeed, these kiosks are gone but children point to cobblers, tea makers and even papad vendors adjacent to their school who they say sell drugs.

Jaiswal of Yuva has seen ganja and afeem being sold within the prohibited 100-metre radius of schools. He says when a school counsellor got a whiff that a vendor was selling them to children she confronted him, but was threatened and told to mind her own business. Dealers stay in touch with kids on WhatsApp. Some stuff is available online too.

Most counsellors argue that the trade cannot flourish without the knowledge of the police. The police counter that the network is so widespread and pervasive that it's tough to tell who might be supplying the cannabis to children. "We have cracked down on medicinal intoxicants and the abuse of those has gone down drastically," says Amandeep Chauhan, drug control officer, Gurgaon.

But the same cannot be said for dry intoxicants like bhang, afeem, marijuana and hashish. In Solapur, cannabis fields were recently burnt by the authorities but it is difficult to keep track of the dozens of new fields that have cropped up.

As compared to cocaine and heroin, weed and hashish are much easier on the pocket. The weekly pocket money is enough to pay for it.

The Bhola goli, a form of bhang, can cost as little as Rs 2 to Rs 5. A packet of weed costs Rs 100 to Rs 200 and is enough for rolling four or five joints. And with 10 gm of hashish, which is purer and costs Rs 1,200 to Rs 1,500, a child can roll 10-15 joints.

For girls, who might hesitate to smoke up, there is the marijuana-laced paste. "They rub it on their gums and it gets absorbed into the blood stream," says Sindhu from the Gurgaon Civil Hospital. "It smells like mouth freshener, so the girls find it safe."

As dependence increases, so does the need for more pocket money. But not all parents oblige. It's normal then for the child to resort to stealing. Beside, after the initial free packets to get the child hooked, the dealer also starts charging more for the dope because he knows the child will not rattle.

Almost every child, age nine and above, today has a mobile phone, says Sindhu. "He sells the phone, tells his parents it got stolen or was lost and then the parents buy him a new phone," he says. So now the child has both money and a new phone. Other things also start disappearing from the house: expensive video games, watches, wallets and even the father's branded shirts.

A safe locker to store valuables has become a must even in nuclear households.

Peer pressure, the need to fit into the group and "be cool" are the key reasons children say they start smoking up.

"The breakdown of the joint family structure, nuclear units with both working parents where the child is left unsupervised for several hours, have removed stability from children's lives," says Puri, the wellness consultant. Parents, exhausted from the day at work, will let a child go to a friend's place even late in the evening. "There is a good chance that the friend's parents too would be out and the children are alone again to do what they please."

Children then start relying more on friends and the internet for company, from where they often get misguided information about things, including marijuana.

They may also inadvertently see older people rolling a joint at a party. The reality is that while marijuana is illegal, it is socially acceptable. Many children are aware that their parents do smoke up (however discreet the parents think they are being, the kids are just that much smarter), says Puri. "Or they have heard stories from their uncles or aunts of the time their parents smoked up when they were younger."

A spin-off is the resurrection of Bob Marley, the high priest of ganja, in popular culture. At Janpath, Delhi's popular flea market, Marley accessories and T-shirts are a huge rage, even amongst kids, so much so that at some shops they are nearly sold out. Then there T-shirts with direct messages like: "Dude! Got Joint?" or "Tu weed badi hai mast mast - Pure Veg".

Parents are often at a loss about what to do on discovering that their child is smoking pot. The first reaction often is denial and then they pass the blame - on friends, teachers and the school. Some choose to change their ward's school on learning that he was smoking up.

Guilt is another reaction. Madhulika Anand, a Delhi-based doctor, has taken a break from work after she found weed in her 15-year-old son's school uniform. "You can say I have put my life on hold," she says.

Sindhu, the Gurgaon psychiatrist, calls it "annihilation anxiety - when you feel the world has come to an end". He knows of parents who have gone into depression and those who have taken child care leave for a year. "Among them are people whose careers call for continuity, like lawyers, doctors and architects. When they eventually get back to work, they will have to rebuild their careers from scratch," he says.

Rarely, but sometimes, desperate parents also turn to detectives. "On an average, two or three parents come to us every month after they notice a drastic change in their child's behaviour or appearance but are unable to draw a satisfactory explanation out of him or her," says Bhavna Paliwal, the founder of Delhi-based Tejas Detective Agency. "They suspect the child is doing drugs."

In some cases, their suspicion turns out to be true.

Some names have been changed on request;

Ranjita Ganesan in Mumbai, Nikita Puri in Bengaluru and Avishek Rakshit in Kolkata contributed to this report

)