Television viewers who grew up in the 1970s knew Bing Crosby as the grandfatherly singing star of wholesome family specials, tuned into by their parents. Crosby was pipe-smoking, unruffled and witty, much like Father O’Malley, the Catholic priest he had played in two oft-rerun films, Going My Way and The Bells of St. Mary’s. By his side were his smiling wife and their model children, none of whom an even vaguely countercultural youth would have wanted to sit next to in the school cafeteria.

Since his music was not theirs, newer generations had no way to know that Crosby had not only changed the course of American popular singing, he had helped create it. It was he who, more than any other vocalist, had freed that art from its turn-of-the-century stiffness and transformed it into conversation. Drawing on black influences, he made pop songs swing, while treating a new invention, the microphone, as if it were a friend’s ear. Without him, Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee, Dinah Shore, Dean Martin and countless other intimate singers could never have happened. A workhorse, he turned out a staggering number of recordings (including dozens of No. 1 hits) as well as films, radio shows and personal appearances. Whatever he did seemed off-the-cuff and effortless.

For all that, his reputation hasn’t much endured. He lacked the qualities that have made Sinatra eternally seductive: coolness, sex appeal, danger, risk and a singing style that opened a window into his hard living and emotional extremes.

Crosby had a far different job. With calm reassurance, he shepherded America through the Depression and World War II, then became a symbol of postwar domestic stability. Crosby applied his soothing baritone to love songs, folk songs, Irish songs, Hawaiian songs, country songs — he sang almost everything and revealed almost nothing. His 1953 memoir, Call Me Lucky, upholds the blithe facade. He seemed trapped in it.

Then, in 1983, six years after Crosby’s death, his oldest son, Gary, wrote his own book, Going My Own Way (with Ross Firestone). In it, he portrays the singer as a monstrous disciplinarian for whom beatings and belittlement were the answers to every filial problem. Gary had become an alcoholic; later in life, two of his brothers, Lindsay and Dennis, shot themselves in the head. Not everyone was surprised. Many who had known Crosby remembered him as cold. In his last television appearances he stares out glumly with eyes of stone, perhaps weary of the role he’d had to play for 40 years.

All this is a biographer’s feast. But with a faded titan like Crosby, should one aim for a single, reader-friendly volume that might attract more than just die-hard fans? Or do the achievements demand a multivolume magnum opus, such as John Richardson is writing on Picasso and Robert Caro on Lyndon B Johnson? And if a writer is enraptured enough to go that route, what to do when there’s lots of personal unpleasantness to address?

Crosby’s biographer Gary Giddins had choices to make. A formidable scholar of jazz and popular song, Giddins is certainly the man for the job. His journalism and his books about Charlie Parker and Louis Armstrong have won him scores of awards.

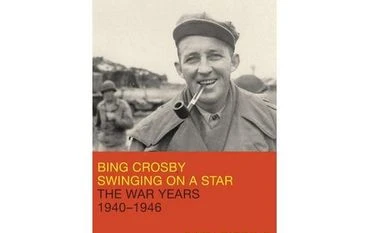

In 2001 he released the 700-plus-page Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams — The Early Years, 1903-1940. Now comes the comparably sized Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star — The War Years, 1940-1946. It’s easy to see why Volume 2 took him so long. As before, Giddins researched a mountain of material to the max, and he lays his findings out with impressive clarity. At the start of the book, Crosby, 37, is America’s greatest star, a “national security blanket” whose role is about to grow as war approaches. Crosby’s weekly radio series, Kraft Music Hall, had made his voice as welcome in the American living room as Franklin Roosevelt’s. Once war was declared, the star took to the road to entertain the troops. The Road movies, his series of slapstick travelogues with Bob Hope, provided goofy escapist fun for the folks back home. In contrast, Crosby’s Oscar-winning portrayal of warm, wise Father O’Malley gave the Catholic Church its best PR.

He tended his image carefully. “My private life is just like the private life of any other middle-class American family,” he declared. Crosby’s wife was Dixie Lee, a winsome songbird who had traded her career (and her peroxide-blond hair) for motherhood. On the air, Crosby depicted their four sons as adorable scamps. In truth, Dixie was a hopeless and nasty drunk, while Crosby, aided by his wife, doled out harsh corporal punishment to keep the boys in line. Gary had it the worst; aside from the beatings, his father humiliated him for a perceived weight problem, calling him Lardass and Bucket Butt. “Bing’s attempt to eradicate a sense of specialness and privilege in his sons,” as Giddins terms it, was undercut by the fact that they were Hollywood kids, trotted out as needed for show.

Bing crosby Swinging on a Star

The War Years, 1940-1946

Author: Gary Giddins

Publisher: Little, Brown & Company

Price: $40

Pages: 724

© 2018 The New York Times

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)