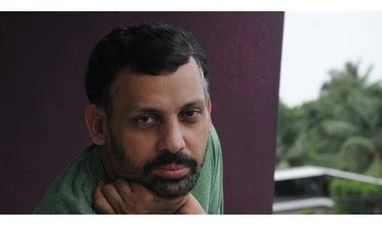

Novelist ANEES SALIM bagged the Sahitya Akademi award this year for his novel The Blind Lady’s Descendants, but as usually, he refused to be present for the prize-distribution ceremony. Salim talks to Uttaran Das Gupta about an inexplicable sadness that motivates him to write. Edited excerpts:

Congratulations on winning the Sahitya Akademi award. You refused to attend the award ceremony saying that a book should be honoured, not the author. Can you explain this a little more? How do you distinguish between honouring one and the other?

Thank you. Well, I have always considered myself as a backstage artist and I am rattled by the mere thought of having to change that mindset. Yes, a book is inseparable from its author and when a book gets an award, the author is indeed honoured. But as someone who doesn’t particularly relish the idea of being seen, I don’t want to be physically present at an award function. I don’t think it makes any difference.

I hope you don’t mind me asking another question about this. When and how did you come to this decision that you would not attend award ceremonies?

I was about 16 years old when I decided to become a writer. Even then, I could not imagine myself doing book tours, signing copies, receiving awards, delivering acceptance speeches or even getting photographed with a book in hand. What appealed to me most about writing was the solitude and quietness that came with it. I got my first book deal after years of waiting and lots of rejections. Even those hardships could not change my decision to stay invisible.

If not fame characterised by awards and recognitions, what motivates you to write?

I see myself as someone brimming with inexplicable sadness. Writing alleviates the pain to a great extent and leaves me less restless. Probably the biggest motivation for me to write is the peace of mind it brings. I try to earn tranquillity the way flyers earn miles. The more I write, the calmer I turn. The day I lose my ability to write I will consider my life irrevocably lost.

When did you start writing, and what were the first things you wrote?

I started writing a day after I dropped out of school. I was 16 years old. I took barely a month to write my first short story, which was sent to The Illustrated Weekly of India, and it took a month to fetch me my first rejection slip. Then I decided to switch to writing novels. I wrote novels set in places I had never been to. But discarded all of them half-way. My first finished manuscript was The Vicks Mango Tree, which earned me lots of rejection slips. To recover from the pain of rejection, I started the next book, which got me even more rejections, then I started writing the next one. By the time I got my first book deal I had three manuscripts ready and they came out in a span of one year.

Tell us a bit about your process. In an interview to The Paris Review, Ernest Hemmingway talks about waking up at the crack of dawn and writing till he reduced two pencils to stubs. Do you have any such formula?

I wake up at 4 in the morning and write till my home is filled with sounds. Sometimes I skip lunch to write for an hour during lunch breaks. Once I have the first draft ready, I will go to another country for a fortnight or so and write for a minimum of 18 hours a day. I repeat this exercise draft after draft until I am sure it is good enough to be shown to the publisher.

Is the process of writing — and revisions — pleasurable at all to you?

Yes, very much. I can do any number of revisions without exhausting myself. I envy people who can sit and write all day without having to worry about anything else. For me, that is the ultimate kind of luxury.

While researching for this interview, I found out that you dropped out of school because you disliked being around too many people. Did you have any formal education or training after that? How important do you feel training is — formally in MFA courses, or informally — essential for a writer?

A few years after I dropped out, I was forced to join a distance-education programme, which would have earned me a degree in political science. But it, too, didn’t work for me. I don’t think you need the backing of an MFA certificate to write a book, but I am told that your MFA background does make a difference when you approach a publisher.

Finally, do you think your decision to withdraw from the literary circles is a sort of subversion or succumbing to the writer-in-the-ivory-tower cliché?

Neither. I just want to stay as invisible as possible.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)