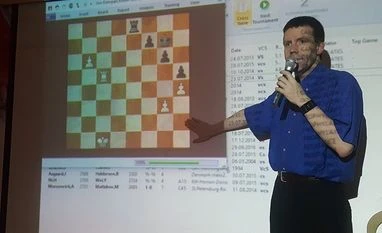

It’s a bright, warm morning in April at the Rathi Tower in Mohan Estate, South Delhi. Jacob Aagaard surveys his 40-strong audience, takes a deep breath and eases off his coat before taking up station in front of the ensemble of projector-whiteboard. One glance tells you that this is not a normal corporate event. Over half the audience is not of voting age. Three boys are visually impaired. Nobody else is wearing a coat and quite a few are in shorts and T-shirts.

Welcome to a chess workshop conducted by an elite coach. Aagaard is a Danish Grandmaster and long-term Glasgow resident who now plays for Scotland. He’s worked for years with Boris Gelfand, the Israeli GM who narrowly lost a title match to Viswanathan Anand in 2012. He’s also coached Indian GM, Surya Shekhar Ganguly, Olympiad champion and gold medallist, Samuel Shankland, and Italian GM, Sabino Brunello, as well as many less well-known players.

Delhi is a stop on a six-nation, multi-city tour. Aagaard is hosted by Delhi Dynamite with logistics support from Chessbase India. Delhi Dynamite is the Rajdhani’s PRO Chess team. PRO Chess is a global league run by Chess.com where city teams play rapid online matches (with proctors to prevent cheating).

The first season features 48 teams with many top players, including world champion, Magnus Carlsen and World No. 2 Wesley So. Delhi Dynamite is knocked out in the quarter-finals by Norway Gnomes (led by Carlsen). And Gnomes loses in the finals to So’s team, the “St Louis Arch Bishops”.

Delhi Dynamite’s social-media advisor, Devanshi Rathi, (she also teaches blind players) says, “We want to keep the buzz going. So we’re putting together programmes like Aagaard’s coaching.” Chessbase India (chessbase.in) is the local arm of popular German website, chessbase.com. It’s managed by International Master Sagar Shah, and his wife, photographer Amruta Mokal. When Aagaard, who says he’s “always up for adventure”, expressed a desire to tour India, they jumped at the chance.

Chess is a simple game. A three-year-old can learn the rules. But simple is not equal to “easy”, as Aagaard points out. There are an unimaginably large number of possible positions. Even super-computers cannot solve chess by brute force, though a cheap smartphone running a free engine can beat Carlsen about as easily as a 30-year-old Maruti 800 can outpace Usain Bolt.

So, how do humans teach themselves to find good moves and assess positions under stringent time constraints? Humans must develop heuristics, simple rules of thumb to help find good moves.

Aagaard’s developed a set of rules. His explanation for how he put these together is disarmingly modest. “I have a very moderate talent and I had to teach myself. Geniuses like Vishy Anand don’t need to,” he says. “The moves flow automatically in Vishy’s head, bang-bang! But I struggle to understand what’s going on.”

Aagaard has played four Olympiads for Denmark, two for Scotland. He’s a polyglot, brought up in an Arab household (“My step-dad calls me Yacub”) and is comfortable across multiple cultures and languages.

His talent is “moderate” only in that he’s not a title contender. Apart from coaching, he’s also an author-editor, who’s written several classics and won four prestigious “chess book of the year” awards for different books.

He is not coincidentally a student of semiotics, which can be described as the mathematics of language and its content. This helps him find genuine answers to rhetorical questions — something that he says is very useful. “I’m a communicator and an artist by instinct. That’s why I love coaching and finding beautiful ideas.”

His speciality publishing house, Quality Chess, runs out of Glasgow. The last seven European champions have all publicly endorsed Quality Chess books, which are used by all top players. “I was writing and editing maybe 35 per cent of content for another chess publisher. I visited my publisher’s house and he lived in a mansion, while I was a student in a tiny flat. I thought it would be more fun (and more lucrative) to do this myself, to my own quality standards. So GM John Shaw (his partner) and I got together,” he says.

Young chess players at the workshop held by Aagaard

Another thing he’s good at is figuring out motivation. Aagaard looks sternly at his audience, “Ask yourself why you make mistakes. But don’t answer, ‘because I am an idiot’. That’s not helpful even if you are. Instead look for concrete improvements. Say, ‘I did not look for this; I did not appreciate that.’ Look for the stuff you missed.”

“I use three basic questions to think about new positions,” Aagaard says. “Locate weaknesses (and strengths) of both sides. Figure out what the opponent is planning. Identify your worst piece. You can do this in any order, but do it all. Often, the best move suggests itself when you answer these three questions.” He admits he never had the “guts” to ask Gelfand to do this explicitly. But top 100 players, Shankland and Ganguly, both swear by the method.

Beyond this, hone your instinct for danger. “Is it a critical position? Then the difference between the best move and the second-best may be the difference between a win and loss. Sometimes chess is about intuition — seeing good ideas. Sometimes it’s calculation and exact solutions like algebra.”

A mix of heuristics, positive focus and certain specifics of calculation work for all levels of players. Aagaard is comfortable with mixed audiences, unlike many coaches. Delhi Dynamite is present at the workshop, with strong GMs like Abhijeet Gupta, Sahaj Grover, Vaibhav Suri and IM Vishal Sareen. There are also budding stars like 16-year-old sub-junior champion Aradhya Garg who shot to fame when he came within an ace of beating Carlsen in PRO Chess. There are also less experienced kids. In Chennai and Kolkata too, Aagaard handled mixed audiences with strong GMs working alongside youngsters of varying experience.

The meat of the “closed session” involves the vegan Aagaard handing out printed sheets of problems where the class applies his methods to find the right moves for the right reasons. After a brief interval, interspersed by moans and mutters from students, he wanders around, looking at answers. Then he does a “group-think” about those positions. Then comes lunch, followed by an “open session” where a game is dissected in details and an AMA (Ask me anything) commences.

Aagaard is seeking a deeper, long-term involvement with India. “There were dozens of talented youngsters here. Plus, I like the food and the Kafkaesque resonances I see everywhere.” He sold out suitcases full of his books and he’s seriously considering an Indian arm of the publishing house. Next time around, the divorced dad might just try to bring along his two daughters — they’re seven and nine and like their dad, they play both chess and the guitar.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)