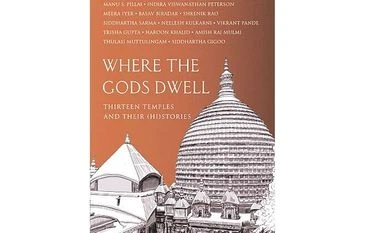

Where the gods dwell: Thirteen temples and their (hi)stories

Author: Manu S Pillai, Trisha Gupta, Vikrant Pande

Publisher: Westland

Price: Rs 499

Pages: 223

For as long as people have travelled, for reasons other than to find fresh farmlands or escape a murdering clan chief, they have gone on pilgrimages. Walking in the footsteps of saints and crusaders, undertaking sacred journeys to temples and shrines or visiting holy cities were once the standard formula for “getaway-travel” among the ancients.

In India, such travel continues to be popular. Proof lies in the proliferation of temple tours and yatras in tourism marketing packages and a state-led push to develop temple circuits and corridors as tourist attractions in recent years. The last National Sample Survey report on Tourism (2017) found the share of religious travel among all overnight travel undertaken by Indians was almost four times the share of travel on business, and over seven-and-a-half times that for education. This means that more and more Indians are travelling for religious purposes.

This book, Where the Gods Dwell: Thirteen Temples and Their (hi)stories, is perhaps a natural fallout of rising interest in such travel and a desire to know more about the temples on the tourism trail. It also fills a gap; much of the history about temples and their architecture is still tucked away in obscure texts or, left to the imagination of flamboyant tour guides. Books like this one are an accessible and more reliable alternative.

The book is a set of 13 essays. It looks at temples from various parts of India and one each in Nepal, Sri Lanka and Pakistan. Each essay is an experiential engagement with a temple of the publisher’s (and/or author’s) choosing.

The essays throw up some interesting insights. It is quite fascinating to see how a deity’s fortunes are so closely linked to those of his or her patrons; a rich devotee (especially if he happens to be a victorious king) can turn humble shrines into grand temples and poor temple towns into thriving tourist spots bustling with devotees almost overnight. At the same time, it is also interesting to note how the same divinity is experienced differently by different cultures. For instance, the god Murugan, who is popularly seen as a god of war in South India, is worshipped as “a cherubic, mischievous child, a handsome stylish prince, a romantic prankster love but not a god of war in Sri Lanka” (“The icon of Jaffna” by Thulasi Muttulingam).

The collection, however, lacks consistency and is missing an editor. As a result, despite having a few good writers, the book starts losing the plot quite early. Some essays are sloppily written and poorly researched, while some fail to make an engaging narrative out of the information at their disposal. There are some writers who have focused on the architectural minutiae to bring out the beauty and grandeur of the temples, but fail to infuse the same passion in their storytelling. Some writers have lost their way in a devotional haze, blunting the impact of the impressive research undertaken for the project. And there are a few who do nothing more than list all the important points about a temple or a place; perspective and insight are both missing from the story.

Among the ones that stand out is the essay that opens the book, by Manu S Pillai (“The God who ate from a coconut shell”) on the Padmanabhaswami temple. He traces the evolution of the deity from “his days of receiving simple naivedyams from a Dalit woman’s hands, to owning veritable mountains of diamonds,” thanks to royal patrons. His research treads lightly on the narrative that looks at the layers of power that the temple has accumulated over the years and from which it draws its wide and abiding influence.

Another essay that leaves a lasting imprint is that about the temple-town Khajuraho (“The sacred and the profane: Experiencing Khajuraho”) by Trisha Gupta. She manages her way deftly around the “exotic erotica” of the sculptures for which the place is known and helps the reader see that the story of the temple town lies as much in the image (of the sculptures) as it does in the people describing the images to tourists (the tour guides). It is only when we take both into account do we truly understand Khajuraho and its influence.

A few essays make the book worth reading, but it could have been a far better read only if the publishers and authors had paid more attention to defining the idea clearly. Why did they choose to write these stories? Why did they choose to write about these temples?

These questions remain unanswered although a foreword-cum-introduction to the book, which is unsigned but presumably carries the editor’s voice, attempts an explanation. It says that the essays and the collection emerged out of a conversation around temples and the unique mix of myth, legend and fantasy in their histories. It also carries a long and rather tedious explanation of the naming of the book — the stories are a mix of mythology, history and local lore and hence, a bracketed qualifier for ‘history’ was the best way to capture what the book wanted to do.

While all of this is fine, the problem is that it does not address the important questions as to why the publisher restricted the list to 13 (was it because it would make for a catchy title)? Or why were the Sabarimala temple complex or the Kashi Vishwanath temple in Varanasi not on the list, given that these are among the oldest and the most “storied” temples today?

But all of this could still be ignored if the essays were held to a common standard on the quality of research and writing, and the book had a consistent voice in its narrative. Unfortunately, that is a big flaw, which keeps this book from becoming a great addition to every bookshelf that it could well have been.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)