Imagine a 22-year-old dropout who lives in the basement of his parents' house and spends his time teasing his three sisters. His Facebook profile is studded with umpteen pictures of pickup beach volleyball and soccer games. His Twitter timeline features posts as random as snapshots of funny fortune cookie predictions, comments on soccer matches and messages from multiple women claiming to suffer from unrequited lust.

Does any of this fit with the mental image of somebody reckoned to be the smartest and most talented chess player in the world? Magnus Carlsen really does seem like an enigma wrapped up in a riddle when one starts to put the disparate elements of his public life and private persona together.

At 22, the Norwegian star has already notched up successes that make greats like Viswanathan Anand and Garry Kasparov look like comparative plodders. He was recognised as a prodigy at nine, and he became a grandmaster barely into his teens. Since then, he's broken record after record.

Carlsen has been World Number 1 for three years and there's a massive distance between him and his nearest rivals. Chess has a rating system that serves as both an index of strength and a tool that predicts likely results between two players. Carlsen is off the scale with a top rating that dwarfs that of the previous record-holder, Kasparov.

His career has already been so impressive that many people seem to think that winning the world title against Anand in Chennai will be a mere formality. Despite the fact that the incumbent, Viswanathan Anand, is universally recognised as an all-time great, the rating differential suggests Carlsen should win the title match by a three-game margin.

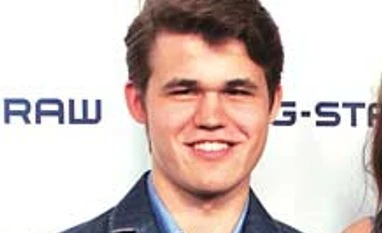

Apart from being very good at the game, Carlsen has that indefinable charisma. His "recognisation quotient" ranges far beyond the game. He makes millions from sponsorships and endorsements. He's handsome and athletic enough to be the clotheshorse for G-Star Raw, one of the most aspirational lines of fashion clothing in the world. He's even been listed among Time magazine's 'hundred most influential people', despite apparently doing nothing more fundamentally earth-shaking than playing chess and modelling. He's been compared to James Dean by his former coach, and to Harry Potter by no less than Kasparov.

Obviously he is an unusual personality. The private persona, and what one knows of his interests, suggests that he is an unusually down-to-earth character as well. Despite being a millionaire many times over, Carlsen preferred to live with his family until recently.

Comparisons between Carlsen and the tormented American genius, Bobby Fischer, are inevitable given that Carlsen is the only man who's generally reckoned to surpass Fischer in terms of sheer talent. But as Carlsen points out himself, "Fischer had a terrible family history and only chess kept him sane. I am just a normal guy who's very good at what he does."

The Carlsen family is indeed very "normal". Father Henrik is an IT consultant while mother Sigrun is a chemical engineer. The three daughters are all students (Magnus is the second of four children). The family often travels together to chess meets and sometimes, the girls play as well. At home, the Carlsen siblings play a lot of monopoly and poker (not for money) and generally hang around. He also likes watching classic British comedy - an interest he shares with the reigning world champion. Both of them can reel off entire scripts from Monty Python and Fawlty Towers with the appropriate sound effects.

Carlsen is an aggressively competitive person who participates in a wide range of physically demanding sports. Apart from skiing, ice-skating and skating, he plays soccer and volleyball passionately and well, according to his first coach and mentor, Simen Agdestein. Agdestein is qualified to judge since, apart from being a chess Grandmaster, he was a soccer international who played several years as a defender for Scottish club Dundee. Agdestein's brother, Espen, is Carlsen's manager.

Carlsen's training for the title match included playing beach volleyball and soccer at a resort in Oman which is roughly similar to Chennai in terms of climate. He also likes to sleep a lot, according to friends, and he can "crash" on demand, a trait he shares with Napoleon Bonaparte. Despite legions of female fans, including a couple of model friends and some embarrassing stalker episodes, he has never had more than what he describes as "passing friendships" with girls.

None of this lifestyle information would be cause for comment, if it wasn't for his being so very good at playing chess. Chess, like music and mathematics, has more than its fair share of prodigies. But even among prodigies Carlsen is special. At 12, he almost beat Kasparov, and the legend who was then World Number 1 admitted he survived that first encounter only because Carlsen lost his nerve at a critical moment. Says Kasparov: "It was obvious that the boy was one helluva talent." By 13, Carlsen was already a Grandmaster and starting to bash through strong adult fields.

His confidence in his ability would be almost brash, except that it is justified. "I never liked losing. I never thought losing is a natural part of the game," he said on the popular US television show, Charlie Rose, in April. In 2000, during a Norwegian youth tournament, a strong junior player described one of his games as, "Well, I played a 9-year-old as white and was a piece up by move 5 and, then, I lost."

The nine-year-old Carlsen had seen an unusual idea and taken a massive but calculated risk. This is something he is still prepared to do, although the level of sophisticated calculation is different when you are playing a top Grandmaster. He is not a "safety first" player and will generally push to try and win games until every possibility is exhausted.

Superficially, there are multiple similarities between Carlsen and Anand. Both come from nations that weren't seen as traditional chess centres. Both learnt to play chess at home - Carlsen was taught by his father, while Anand was taught by his mother. Both had notably remarkable memories with the capacity to absorb a lot of information very quickly if they got interested in a subject. Anand took up astronomy as a hobby, memorising star charts, while Carlsen memorised the flags and populations of different nations as a child. Both were good at solving puzzles.

As chess prodigies, they made their mark early, beating strong players with apparent ease and shouldering their way into the elite. Their rise sparked explosions of popularity in their respective nations with a large number of local players taking up the game. It also led to sponsorship from local businesses, aiding the development of local tournament circuits in India and Norway.

Drill a little deeper though and the generational differences become more obvious. Carlsen is an "Internet baby" - he was born just as the infotech revolution started to change the game. He had access to strong chess engines from the beginning of his career.

In a personal blog, Henrik says that Magnus spent countless hours playing online chess at the Internet Chess Club and at Playchess from around 2000 onwards. This was exposure that nobody in Anand's generation could have dreamt of, and it may have led to an accelerated pace of development.

Carlsen has also had access to strong coaches and to sponsorships almost from the very beginning. Norway is much closer geographically to the great European chess centres, making it easier for Carlsen to get exposure. By contrast, Anand was already in his 20s and a top player before the Internet and chess engines and databases became ubiquitous.

Carlsen was being trained by Agdestein from age 10 and he was being sponsored by Computas, a Norwegian IT company. Then Microsoft Norway took over as a sponsor, and after that, Smartfish. Obviously father Henrik worked his personal contacts to get those deals, but, equally obviously, the talent was so stunning that sponsors were prepared to back him. Carlsen currently has an association with Arctic Securities, a financial institutional investor, and with the legal firm, Simonsen. In 2009-10, his sponsors paid for a 13-month coaching stint with Kasparov. While Anand had his sponsors - Ramco and NIIT, for example - he did not have this level of consistent support.

In terms of style as well, they are very different. Anand likes complicated positions where superior analysis and home-preparation can deliver an edge. His best games tend to be fast knockouts where he gets to deliver a series of stunning punches. He doesn't particularly enjoy playing out long endgames and if he reaches an equal position without much in the way of prospects, he generally prefers to draw it quickly rather than expend energy.

Carlsen is an "anti-theoretician" who prefers to avoid situations that are susceptible to home analysis. "I normally do what my intuition tells me to do. Most of the time spent thinking is just to double-check," he told London's Financial Times last year. This means he often reaches positions that are not particularly superior and, occasionally, somewhat inferior. However, he is prepared to expend enormous energy over the board and play things out to the very end. He wins a lot of long endgames and his technical skills are astounding both in offence and in defence. His high scoring rate makes him unquestionably a superior tournament player - Carlsen often wins tournaments with scores that leave rivals far behind.

However, match dynamics are different, and here Anand's far greater experience could count. A match is all about winning one game more than the rival and Carlsen will have to make the mental adjustments required, whereas Anand knows exactly what he needs to do.

On paper, and on the basis of the last three or four years, Carlsen should win the World Championship, to start today in Chennai, with something to spare. In practice, it's a short match and if Anand has discovered any weaknesses in the Norwegian's game, Carlsen might not have time to adjust. The coronation of Carlsen as world champion is inevitable. But it might just be postponed by a couple of years if Anand can raise his game. If he doesn't, then the crown will pass on to a new generation represented by a fiesty 22-year-old.

Does any of this fit with the mental image of somebody reckoned to be the smartest and most talented chess player in the world? Magnus Carlsen really does seem like an enigma wrapped up in a riddle when one starts to put the disparate elements of his public life and private persona together.

At 22, the Norwegian star has already notched up successes that make greats like Viswanathan Anand and Garry Kasparov look like comparative plodders. He was recognised as a prodigy at nine, and he became a grandmaster barely into his teens. Since then, he's broken record after record.

Carlsen has been World Number 1 for three years and there's a massive distance between him and his nearest rivals. Chess has a rating system that serves as both an index of strength and a tool that predicts likely results between two players. Carlsen is off the scale with a top rating that dwarfs that of the previous record-holder, Kasparov.

His career has already been so impressive that many people seem to think that winning the world title against Anand in Chennai will be a mere formality. Despite the fact that the incumbent, Viswanathan Anand, is universally recognised as an all-time great, the rating differential suggests Carlsen should win the title match by a three-game margin.

Apart from being very good at the game, Carlsen has that indefinable charisma. His "recognisation quotient" ranges far beyond the game. He makes millions from sponsorships and endorsements. He's handsome and athletic enough to be the clotheshorse for G-Star Raw, one of the most aspirational lines of fashion clothing in the world. He's even been listed among Time magazine's 'hundred most influential people', despite apparently doing nothing more fundamentally earth-shaking than playing chess and modelling. He's been compared to James Dean by his former coach, and to Harry Potter by no less than Kasparov.

Obviously he is an unusual personality. The private persona, and what one knows of his interests, suggests that he is an unusually down-to-earth character as well. Despite being a millionaire many times over, Carlsen preferred to live with his family until recently.

Comparisons between Carlsen and the tormented American genius, Bobby Fischer, are inevitable given that Carlsen is the only man who's generally reckoned to surpass Fischer in terms of sheer talent. But as Carlsen points out himself, "Fischer had a terrible family history and only chess kept him sane. I am just a normal guy who's very good at what he does."

* * *

The Carlsen family is indeed very "normal". Father Henrik is an IT consultant while mother Sigrun is a chemical engineer. The three daughters are all students (Magnus is the second of four children). The family often travels together to chess meets and sometimes, the girls play as well. At home, the Carlsen siblings play a lot of monopoly and poker (not for money) and generally hang around. He also likes watching classic British comedy - an interest he shares with the reigning world champion. Both of them can reel off entire scripts from Monty Python and Fawlty Towers with the appropriate sound effects.

Carlsen is an aggressively competitive person who participates in a wide range of physically demanding sports. Apart from skiing, ice-skating and skating, he plays soccer and volleyball passionately and well, according to his first coach and mentor, Simen Agdestein. Agdestein is qualified to judge since, apart from being a chess Grandmaster, he was a soccer international who played several years as a defender for Scottish club Dundee. Agdestein's brother, Espen, is Carlsen's manager.

Carlsen's training for the title match included playing beach volleyball and soccer at a resort in Oman which is roughly similar to Chennai in terms of climate. He also likes to sleep a lot, according to friends, and he can "crash" on demand, a trait he shares with Napoleon Bonaparte. Despite legions of female fans, including a couple of model friends and some embarrassing stalker episodes, he has never had more than what he describes as "passing friendships" with girls.

None of this lifestyle information would be cause for comment, if it wasn't for his being so very good at playing chess. Chess, like music and mathematics, has more than its fair share of prodigies. But even among prodigies Carlsen is special. At 12, he almost beat Kasparov, and the legend who was then World Number 1 admitted he survived that first encounter only because Carlsen lost his nerve at a critical moment. Says Kasparov: "It was obvious that the boy was one helluva talent." By 13, Carlsen was already a Grandmaster and starting to bash through strong adult fields.

His confidence in his ability would be almost brash, except that it is justified. "I never liked losing. I never thought losing is a natural part of the game," he said on the popular US television show, Charlie Rose, in April. In 2000, during a Norwegian youth tournament, a strong junior player described one of his games as, "Well, I played a 9-year-old as white and was a piece up by move 5 and, then, I lost."

The nine-year-old Carlsen had seen an unusual idea and taken a massive but calculated risk. This is something he is still prepared to do, although the level of sophisticated calculation is different when you are playing a top Grandmaster. He is not a "safety first" player and will generally push to try and win games until every possibility is exhausted.

* * *

Superficially, there are multiple similarities between Carlsen and Anand. Both come from nations that weren't seen as traditional chess centres. Both learnt to play chess at home - Carlsen was taught by his father, while Anand was taught by his mother. Both had notably remarkable memories with the capacity to absorb a lot of information very quickly if they got interested in a subject. Anand took up astronomy as a hobby, memorising star charts, while Carlsen memorised the flags and populations of different nations as a child. Both were good at solving puzzles.

As chess prodigies, they made their mark early, beating strong players with apparent ease and shouldering their way into the elite. Their rise sparked explosions of popularity in their respective nations with a large number of local players taking up the game. It also led to sponsorship from local businesses, aiding the development of local tournament circuits in India and Norway.

Drill a little deeper though and the generational differences become more obvious. Carlsen is an "Internet baby" - he was born just as the infotech revolution started to change the game. He had access to strong chess engines from the beginning of his career.

In a personal blog, Henrik says that Magnus spent countless hours playing online chess at the Internet Chess Club and at Playchess from around 2000 onwards. This was exposure that nobody in Anand's generation could have dreamt of, and it may have led to an accelerated pace of development.

Carlsen has also had access to strong coaches and to sponsorships almost from the very beginning. Norway is much closer geographically to the great European chess centres, making it easier for Carlsen to get exposure. By contrast, Anand was already in his 20s and a top player before the Internet and chess engines and databases became ubiquitous.

Carlsen was being trained by Agdestein from age 10 and he was being sponsored by Computas, a Norwegian IT company. Then Microsoft Norway took over as a sponsor, and after that, Smartfish. Obviously father Henrik worked his personal contacts to get those deals, but, equally obviously, the talent was so stunning that sponsors were prepared to back him. Carlsen currently has an association with Arctic Securities, a financial institutional investor, and with the legal firm, Simonsen. In 2009-10, his sponsors paid for a 13-month coaching stint with Kasparov. While Anand had his sponsors - Ramco and NIIT, for example - he did not have this level of consistent support.

* * *

In terms of style as well, they are very different. Anand likes complicated positions where superior analysis and home-preparation can deliver an edge. His best games tend to be fast knockouts where he gets to deliver a series of stunning punches. He doesn't particularly enjoy playing out long endgames and if he reaches an equal position without much in the way of prospects, he generally prefers to draw it quickly rather than expend energy.

Carlsen is an "anti-theoretician" who prefers to avoid situations that are susceptible to home analysis. "I normally do what my intuition tells me to do. Most of the time spent thinking is just to double-check," he told London's Financial Times last year. This means he often reaches positions that are not particularly superior and, occasionally, somewhat inferior. However, he is prepared to expend enormous energy over the board and play things out to the very end. He wins a lot of long endgames and his technical skills are astounding both in offence and in defence. His high scoring rate makes him unquestionably a superior tournament player - Carlsen often wins tournaments with scores that leave rivals far behind.

However, match dynamics are different, and here Anand's far greater experience could count. A match is all about winning one game more than the rival and Carlsen will have to make the mental adjustments required, whereas Anand knows exactly what he needs to do.

On paper, and on the basis of the last three or four years, Carlsen should win the World Championship, to start today in Chennai, with something to spare. In practice, it's a short match and if Anand has discovered any weaknesses in the Norwegian's game, Carlsen might not have time to adjust. The coronation of Carlsen as world champion is inevitable. But it might just be postponed by a couple of years if Anand can raise his game. If he doesn't, then the crown will pass on to a new generation represented by a fiesty 22-year-old.

)