It was a little after 7.15 in the evening on that spring day of Thursday, April 4, 1968. I was on my way to Willard Straight Hall from the Cornell University Library in Ithaca in upstate New York. I usually took a break at that time for the evening news and a bit of supper at the Straight, which housed the student union and a large cafeteria. In those days, before anyone had ever dreamt of 24x7 news media, one read the news in the morning papers or watched it in the evening on television. My assistantship barely allowed me to keep body and soul together, so I had to watch the news in the Ivy Room of the Straight. That was a tussle on most days, as a vast majority of undergraduates there were die-hard fans of the evening re-runs of Star Trek with William Shatner’s Captain Kirk and Leonard Nimoy’s pointy-eared Commander Spock. One had to almost fight to tune into the news.

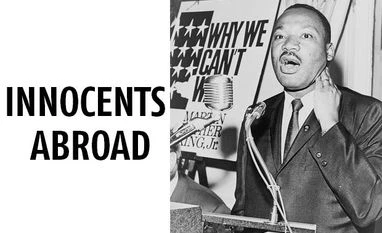

That Thursday evening was different. The news was already halfway through and Walter Cronkite was sombrely announcing that the Reverend Dr Martin Luther King was shot by an unknown assailant when he appeared on his Memphis, Tennessee motel room balcony at 6 pm local time. One could hear a pin drop in the jam-packed room. Most were too stunned to react, but some sobs were audible. King’s death was announced an hour later.

Almost exactly two months later, shortly past midnight of June 5, Senator Robert F Kennedy was shot in a Los Angeles hotel lobby. He had just made a victory speech after winning the California Democratic primary election in his bid for the American presidency. Extensive surgeries could not save him. He died a day later, in the early hours of June 6. Those two Thursdays, nine weeks apart, bookended events that were to profoundly influence America and the world. They found resounding echoes across the world in the spring, the summer and the year that followed.

I went to the United States in 1965 from the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, a powerhouse school then as now, but the world did not know it. It was only seven years old. We were among the first of its graduates to enter American institutions. We were the pilgrim fathers of the now ubiquitous Indian techno geeks.

As I look back fifty years later, 1968 was the greatest point of inflexion in my existence. I was midway through the six most exhilarating years of my time in the United States. I met the woman of my life, who still has me all dreamy-eyed. I was to do my doctoral dissertation on China, having studied Mandarin for two years and secured a fellowship. But in the midst of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, an Indian with American sponsorship had less chance of getting a Chinese visa than a snowflake in hell.

King’s assassination led to protests across the country. Black ghettos went up in flames in city after major city. Black power became the battle cry. Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the gold and bronze medallists in the 200 m sprint at the Mexico City Summer Olympics in October that year, raised their clenched fists in a “black power salute”. That picture was the most graphic representation of the new black identity. Black studies departments sprang up in most major universities.

The war in Vietnam was at its lowest ebb in public opinion after the Tet Offensive that year. The older, more conservative, Americans were troubled by the rising body count of the US troops and nightly images of body bags arriving from that ravaged country. Their younger, more liberal, compatriots were outraged by the immorality of the war waged on a small country with great savagery. “Hey, hey LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” was a refrain heard not only in the increasingly frequent peace demonstrations in Washington DC but elsewhere as well.

President Lyndon Johnson opted out of re-election. The Democrats dutifully nominated his vice president, Hubert Humphrey, in the summer. The Chicago Convention witnessed vigorous anti-war protests, ruthlessly put down by the police. Norman Mailer chronicled this scathingly in his brilliant The Armies of the Night: History as a Novel/The Novel as History. Tom Hayden, the young leader of Students for a Democratic Society and Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, were arrested along with five others. The trial of the Chicago Seven became a cause célèbre. Humphrey, an otherwise decent and liberal politician, lost in November to Richard Nixon, who had vowed to end the war. But when Nixon had to resign in disgrace in 1974 after the Watergate disclosures, the war was still raging.

The loss of two charismatic leaders in quick succession, the continuing obscenity of the war in Southeast Asia and the rise of a reactionary national leadership was to prove cathartic for America. Demonstrations and impassioned debates continued across the country. Daniel Berrigan, a Jesuit at Cornell, and his brother Phillip, a Catholic cleric, burnt draft records at Catonsville, Maryland. Young men, including Bill Clinton, fled the country rather than serve as conscripted soldiers. Some like George W Bush found softer havens such as service in the National Guard.

It was not just the war that agitated the conscience of America. Many corporates and even some universities had substantial investments in apartheid-ruled South Africa. Nelson Mandela had just been incarcerated, but was not yet a household name. Agent Orange, a defoliant widely used in Vietnam, raised issues of environmental damage. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Ralph Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed became clarion calls for the incipient ecological and anti-automobile concerns. Islam was a religion in far-off places. A friend who had travelled to Afghanistan called it the most desolate land on earth and said that they probably fed rocks to their goats. The audience laughed; no one had heard of it, anyway.

This combination of concerns about imperialist wars, civil rights (and early consciousness of gender equality) and our fragile ecology became universal galvanising agents against ageing and insensitive political systems. Rock music was the lingua franca of protest anthems. Jack Kerouac and Bob Dylan were the acclaimed Beat Generation troubadours. Alternate life styles raged as much against traditional family structures as against the social strait-jacket.

Across the Atlantic, Europe, especially France, too witnessed large protests. General Charles de Gaulle, hailed as the saviour of France twice over, had begun his second seven-year term as the president of the fourth republic in 1968. He held a referendum on his rule later in the year when he became the target of street protests. Although he won it narrowly, he resigned in early 1969, sensing correctly that the tide was running out.

In retrospect, it appears amazing that all these and many more such events could have happened in a single calendar year. Even more astounding is the fact that they were led by sheer numbers of unknown innocent young people, naïve in their firm belief that they could change the world.

E J Dionne, in a reflective column in The Washington Post in 2008 on the fading of liberalism, observed that liberalism is the natural ideology of innocence, just as boundless optimism is its hallmark.

We have seen a few such sporadic, spontaneous and exuberant movements since then: the 1975-76 agitations that led to the collapse of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, the 2008 “Yes we can!” campaign of Barack Obama, the brief flickering of the Anna Hazare movement in 2010, the Arab Spring of 2011 that saw a wholesale overthrow of anciens régimes across North Africa, and the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations of 2011. They gave hope, only to die in no time at all.

It is now clear that something even more precious has been dying ever since: our collective innocence. Half a century after those halcyon days, the world is a very different place. Free speech and liberal thought, the very essence of hope, are under siege everywhere. The prevailing mood varies from deep cynicism to sheer despair. From Hungary to the Maldives and from Turkey to Malaysia, tinpot dictators have grabbed power. Emperor Xi Jinping and Tsar Vladimir Putin have lately perpetuated their rule. No words can describe the vulgarity and inanity of the abomination that is Donald Trump. India, as the veteran diplomat K Shankar Bajpai observed recently, “faces more dangerous challenges than it is even aware of” (The Indian Express, March 30, 2018).

Ten years after 1968, Buckminster Fuller, that paragon of optimism and high priest of the power of technology, delivered an address in Ahmedabad, where I was at the time teaching at another powerhouse school in the making. He begged the audience to listen to him carefully, because he had many solutions to offer and the time was short. The crowd did not understand him, but applauded politely. He would be roundly booed today at a similar gathering.

Memories of 1968 bring to mind William Wordsworth: “Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive,/ But to be young was very heaven!” Those young warriors, now aged, can only clutch at the Solomonic wisdom, “This, too, shall pass.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)