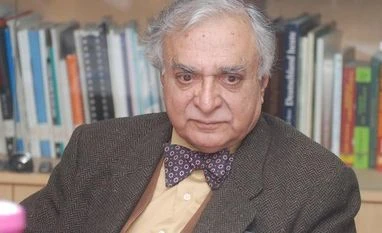

For five years, from about 2014, whenever he was in India, he and I sat in adjacent chairs at the weekly editorial meetings of this newspaper. He would shuffle in with his walking stick, mask and, in the summer, his straw hat. At first he would bring along his pipe but later on I think he gave up tobacco.

In these five years, I had just one grievance against him. As the designated supplier of samosas, I took around 2,500 samosas to the meeting, at the rate of 10 per meeting over about 250 weeks. He never took one, never, not once. In fairness, though, he didn’t touch the biscuits, either.

He was past his academic prime by then and had also developed fixed views on most things. But this is better than those who develop fixed views in their forties. It wasn’t such a bad thing in his case also because he was rarely wrong. And, above all, he still knew his economic theory. Most Indian economists have either forgotten it or never knew it to begin with.

Born in Lahore in 1940 and educated at the traditional triad of Doon School, St Stephens and Oxford University, he drifted away to the US at the end of the 1980s. Before that, he had taught in England. He eventually became a professor of economics at UCLA.

His research interests were hugely varied and you could find the entire list on his webpage. Not a lot of it was very influential in the mainstream economic thinking, but he did stick to his guns that always had two barrels — classicism and liberalism. These two values defined the man.

There were many things that he took a dim view of. China was one of them. He regarded its economic policies as bizarre. In many articles in this paper as well as in other publications, he would praise its achievements and then go on to say these were not sustainable. Human freedom is what makes for long-lived greatness, he believed, and the communist party’s lack of regard for them would hold China back. The current dispensation in China was as much a source of annoyance for him as was the current Democratic Party in the US. Stupid fellows, he said.

On Brexit he was a hawk which is not surprising, considering he was a member of the UK’s Shadow Chancellor’s advisory group for nine years from 2000 to 2009. The Labour Party was in power then. He thought Britain would gain by opting out.

He said he had voted in 1975, all bright eyed and bushy tailed, for Britain joining the common market. But what “I, along with many of my peers in 1975, came to see as the Common Market, evolved into the EU; we had been lied to by the Europhile political elites. Whilst selling us a free-trading area they were in fact surreptitiously co-opting us in the creation of a political union, a United States of Europe: a state run by unelected technocrats.”

But it was not just China and the EU that annoyed him. He was equally derisive of India. The excessive focus on ‘people’ was all right for politics and politicians, he thought, but not for economics and economists. He would quietly laugh at economists who batted persistently for redistribution without reference to its costs.

At the end of the 1980s he wrote a book that passed largely unnoticed in India. It was a three-volume affair and was called The Hindu Equilibrium. It was a vast survey of India and its economy over two thousand years and more.

Volume One was about cultural stability. Volume Two was about labour. Volume Three is an abridged edition. The book irritated economists and historians both. It was that sort of book which I would venture to suggest is the very essence of a good intellectual that Deepak Lal was.

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)