He has a seemingly quotidian life in suburbs with a loving girlfriend (Golshifteh Farahani) and a lovely dog and a post-prandial beer at his neighbourhood bar. But every day he writes poems between work or lunch break on topics as disparate as match boxes and his childhood. The fun chattering among the passengers keeps his creative juices flowing as well. The only music in his working life is the pressurised hiss of the bus doors.

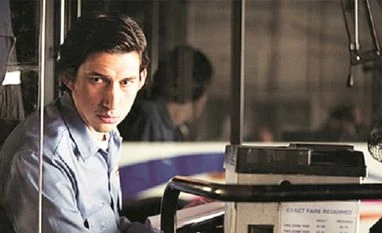

The movie’s most levitating moments are when Paterson’s musings on the page are transposed on the screen. Driver is simply magical in the role of Paterson. It’s hard to imagine anyone else as the pituitive freak who is broad-chested, like a beefier version of Karl Ove Knausgaard, but with a tender heart. The extraordinary warmth that he imbues his character with makes it near impossible to detect the sources of his special access to the human heart. Him as Paterson reminded me, not in a bad way, of 19th century novelist Thomas Love Peacock’s famous quipped about a poet’s mind, “The march of his intellect is like that of a crab, backwards.”

The protagonist seems to have internalised the Amiri Baraka motto: “Art-ing is what makes art.” Despite his girlfriend’s nagging, Paterson has least interest in getting a photocopy of his secret notebook full of his poems until the final act when he’s full of remorse because of his unwilling nature. Thanks to a deus ex machine in the form of a Japanese tourist sharing the bench with him in a park by the Passaic Falls, the movie ends with a distraught Paterson again going back to the blank page.

Lerner has loftier expectations from the verse. “You’re moved to write a poem, you feel called upon to sing, because of [a] transcendent impulse. But as soon as you move from that impulse to the actual poem, the song of the infinite is compromised by the finitude of its terms.”

Compared to Paterson’s hard boiled poetry (work of New York City bard Ron Padgett), Lerner is exacting from this particular form of arts, “The poet is a tragic figure. The poem is always a record of failure in that it cannot live up to the poet’s own expectations.”

Thankfully, our protagonist is untethered from such genre conventions. His world is fey-like with twins all around him (even his favourite poet is William Carlos Williams) and a girlfriend who has a twin obsession of being a country singer and “cupcake queen of Paterson”. I nearly wept tears of joy when a young girl says it’s awesome that “a bus driver reads Emily Dickinson”. The whole sequence involving her reading her own poetry has to be one of the most otherworldly movie scenes of 2016.

Jarmusch narrates the movie over the course of seven days of Paterson’s life. In the most Jarmuschian way, we get to know about the inner workings of a budding artist’s mind. This is the most Groundhog Day-esque movie I have watched after Bela Tarr’s The Turin Horse.

Not many movies get made anymore on the creative process of an artist, even if Paterson gets cloying at times and the fact that the movie’s conflict point is a little dog. Recent movies like Neruda and A Quiet Passion explore a thread of the poet’s life but not about the work as such. Movies like Paterson might just make Lerner understand that sometimes people need to get things out of their system, even if it’s in a prosaic manner and that’s alright, really.

jagannath.jamma@bsmail.in

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)