Fyat Fyat Sain Sain" an old-timer called Madan tells a new recruit in a make-believe world. Learn this mantra by heart and you will fly, the newbie is told. Named DS after Madan's favourite brand of whisky, this newbie, much like Madan, is a Fyataru - a strange class of humans that develops the ability to fly and thrives on the pleasure derived from carrying out anarchic attacks on evil political forces.

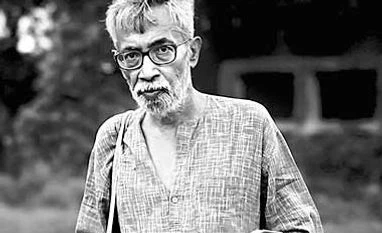

The antics of these flying humans is just one of the many reasons why Nabarun Bhattacharya is remembered as a radical writer, believes Kolkata-based artist and film maker, Madhuja Mukherjee. The only son of playwright and film personality Bijon Bhattacharya, who led the Indian People's Theatre Association movement during the 1940s, and well-loved writer Mahasweta Devi, Bhattacharya, passed away in 2014 at the age of 66.

Among many remarkables, including the Sahitya Akademi-winning Herbert and a poem whose title was the poster slogan for the historic Shahbag protest movement in Dhaka in 2013 (Ei Mrityu Upotyoka Aamar Desh Na - This Valley of Death Is Not My Country), he left behind an unfinished novel and a host of ideas.

An associate professor at the department of film studies, Jadavpur University, Mukherjee has received a grant from India Foundation for the Arts to produce a graphic narrative of Bhattacharya's Lubdhak - The Dog Star (2006). And along with three-time National Award-winning cinematographer and director Avik Mukhopadhayay, Mukherjee is also working on a feature-length stop motion animation film based on the same book.

Bengali for Canis Majoris (the brightest star in the constellation), Lubdhak continues to be one of Bhattacharya's most underrated works. To an extent this is because it's easier to associate with the human element in the Fyatarus - in one story, DS steals a "colour" television to watch the World Cup and then returns it after he's done, creating much confusion in the process. In contrast, Lubdhak's protagonists are dogs who reside on the city's streets.

Set in a dystopic Kolkata where the city council has decided to give the place a new avatar via a beautification drive, the council agrees that all street dogs must be banished. The council then weighs between different methods to make this drive a success - would firing squads be more hassle-free or would poisoning the dogs in the darkest hours of the night be more effective to carry out a canine genocide, they wonder.

"Bhattacharya imagined many things before they happened - look at how stray dogs are being killed. His writing shows that he had a good understanding of politics. He predicted the rise of the Trinamool Congress in 2002 itself in Kangal Malsat," says Mukherjee who has previosuly worked on a Bengali graphic novel version of the book.

Translated as "war cry of beggars", Kangal Malsat, featuring Fyatarus, was made into a film by Suman Mukhopadhyay. The film came under heavy censorship, citing "distortion of history, excessive use of abusive language, sexuality and the portrayal of social movements in a harmful way". Mukhopadhyay's directorial debut, about a local celebrity who claims to talk to the dead, was also inspired by Bhattacharya's Herbert.

An ultra-Leftist, Bhattacharya never aligned with any party. While he was quite critical about issue-based politics such as caste and gender, a criticism against him is that his protagonists were only male .

"It's true that there are primarily male characters in his novels. But his men are really weak and his stories are not about the macho lot; they are about drunkards and failures. What I like is that he was never sentimental of issues that divided the larger political goal - issues such as gender and poverty," says Mukherjee. In Kangal Malsat, for instance, he's critical of the poor when they begin aligning with the establishment.

"But I was more sensitive to the issue of gender," say Mukherjee, "I had asked him why there were only flying men, where were the flying women?" She was asked to make one of the female characters, Kali, a Fyataru. In the graphic form version of the book, Kali has grown wings.

One can only find one of Bhattacharya's novels, Herbert, in English. Translated by Arunava Sinha, it's called Harbert (2011).

And though Mukherjee and Mukhopadhayay hope that Bhattacharya's works are translated soon, Mukherjee cautions that the task wouldn't be an easy one. "His language was very colloquial, and he invented words too. He'd particularly merge two abusive words often and create a new one. That kind of exuberant language is only heard on the streets, and almost never in literature."

This variety of language was incidentally Bhattacharyya's weapon against the bhadralok culture, against literary elitism. In Nabarun (2014), a documentary made by Q, aka Qaushiq Mukherjee, on the writer, Bhattacharyya talks about how every "normal human being" should use slangs. "Slangs are just another mode of expression. It's vitality and strength of language, but the appreciation of literature is still stuck at (such) an imbecile level that we still discuss these issues," says Bhattacharyya, seen sitting in a taxi in the film.

Mostly in literature and cinema, iconic images often associated with the city of Kolkata include those from a known stable, such as the Howrah Bridge, Victoria Memorial and trams. But Bhattacharya's work draws one's attention to the sub-cities that exist. He takes you to the city's underbelly, says Mukherjee, adding how Lubdhak easily lends itself to a visual narrative.

While Kangal Malsat is in Bengali, Lubdhak, the graphic novel, will be in English and the stop motion animation will have both English and Bengali voices. Hoping that Lubdhak, in its classic black-and-white character, could appeal to adults too, they hope to start shooting the film next month.

Surrounded by shelves teeming with old newspapers, Twain, Proust, Lorca and Lenin, he was a positive person even when he was diagnosed with cancer, remembers Avik Mukhopadhayay. When a cartoon featuring Mamata Banerjee raked up a mighty big storm in 2012, it found a place on Bhattacharya's shelf too. "We've never had a funnier government," he had then said in an interview.

"He has always had a really large following among the youth," says Mukherjee, suggesting his fierce, anti-establishment persona could have something to do with the pull he has. But Bhattacharya was always wary of being put on a pedestal. Even his Fyatarus, he believed, weren't fighting for recognition, but "reorganisation" so that they could live in harmony.

In Lubdhak, Bhattacharya's canine protagonists not only focus on overcoming the oppressor, but also rejecting them. And these underdogs turned heroes were all dreamt of by a rebel who spent hours seated by the window in his compact ground floor apartment in Kolkata, watching the canine inhabitants of the society, and how much they had in common with man.

The antics of these flying humans is just one of the many reasons why Nabarun Bhattacharya is remembered as a radical writer, believes Kolkata-based artist and film maker, Madhuja Mukherjee. The only son of playwright and film personality Bijon Bhattacharya, who led the Indian People's Theatre Association movement during the 1940s, and well-loved writer Mahasweta Devi, Bhattacharya, passed away in 2014 at the age of 66.

Among many remarkables, including the Sahitya Akademi-winning Herbert and a poem whose title was the poster slogan for the historic Shahbag protest movement in Dhaka in 2013 (Ei Mrityu Upotyoka Aamar Desh Na - This Valley of Death Is Not My Country), he left behind an unfinished novel and a host of ideas.

More From This Section

Bhattacharya's is a legacy that should be translated and shared beyond an audience that can read Bengali, believes Mukherjee. "He has always been a cult writer whose work can only be compared to those who've done work in the field of magic realism abroad," she says.

An associate professor at the department of film studies, Jadavpur University, Mukherjee has received a grant from India Foundation for the Arts to produce a graphic narrative of Bhattacharya's Lubdhak - The Dog Star (2006). And along with three-time National Award-winning cinematographer and director Avik Mukhopadhayay, Mukherjee is also working on a feature-length stop motion animation film based on the same book.

Bengali for Canis Majoris (the brightest star in the constellation), Lubdhak continues to be one of Bhattacharya's most underrated works. To an extent this is because it's easier to associate with the human element in the Fyatarus - in one story, DS steals a "colour" television to watch the World Cup and then returns it after he's done, creating much confusion in the process. In contrast, Lubdhak's protagonists are dogs who reside on the city's streets.

Set in a dystopic Kolkata where the city council has decided to give the place a new avatar via a beautification drive, the council agrees that all street dogs must be banished. The council then weighs between different methods to make this drive a success - would firing squads be more hassle-free or would poisoning the dogs in the darkest hours of the night be more effective to carry out a canine genocide, they wonder.

"Bhattacharya imagined many things before they happened - look at how stray dogs are being killed. His writing shows that he had a good understanding of politics. He predicted the rise of the Trinamool Congress in 2002 itself in Kangal Malsat," says Mukherjee who has previosuly worked on a Bengali graphic novel version of the book.

Translated as "war cry of beggars", Kangal Malsat, featuring Fyatarus, was made into a film by Suman Mukhopadhyay. The film came under heavy censorship, citing "distortion of history, excessive use of abusive language, sexuality and the portrayal of social movements in a harmful way". Mukhopadhyay's directorial debut, about a local celebrity who claims to talk to the dead, was also inspired by Bhattacharya's Herbert.

An ultra-Leftist, Bhattacharya never aligned with any party. While he was quite critical about issue-based politics such as caste and gender, a criticism against him is that his protagonists were only male .

"It's true that there are primarily male characters in his novels. But his men are really weak and his stories are not about the macho lot; they are about drunkards and failures. What I like is that he was never sentimental of issues that divided the larger political goal - issues such as gender and poverty," says Mukherjee. In Kangal Malsat, for instance, he's critical of the poor when they begin aligning with the establishment.

"But I was more sensitive to the issue of gender," say Mukherjee, "I had asked him why there were only flying men, where were the flying women?" She was asked to make one of the female characters, Kali, a Fyataru. In the graphic form version of the book, Kali has grown wings.

One can only find one of Bhattacharya's novels, Herbert, in English. Translated by Arunava Sinha, it's called Harbert (2011).

And though Mukherjee and Mukhopadhayay hope that Bhattacharya's works are translated soon, Mukherjee cautions that the task wouldn't be an easy one. "His language was very colloquial, and he invented words too. He'd particularly merge two abusive words often and create a new one. That kind of exuberant language is only heard on the streets, and almost never in literature."

This variety of language was incidentally Bhattacharyya's weapon against the bhadralok culture, against literary elitism. In Nabarun (2014), a documentary made by Q, aka Qaushiq Mukherjee, on the writer, Bhattacharyya talks about how every "normal human being" should use slangs. "Slangs are just another mode of expression. It's vitality and strength of language, but the appreciation of literature is still stuck at (such) an imbecile level that we still discuss these issues," says Bhattacharyya, seen sitting in a taxi in the film.

Mostly in literature and cinema, iconic images often associated with the city of Kolkata include those from a known stable, such as the Howrah Bridge, Victoria Memorial and trams. But Bhattacharya's work draws one's attention to the sub-cities that exist. He takes you to the city's underbelly, says Mukherjee, adding how Lubdhak easily lends itself to a visual narrative.

While Kangal Malsat is in Bengali, Lubdhak, the graphic novel, will be in English and the stop motion animation will have both English and Bengali voices. Hoping that Lubdhak, in its classic black-and-white character, could appeal to adults too, they hope to start shooting the film next month.

Surrounded by shelves teeming with old newspapers, Twain, Proust, Lorca and Lenin, he was a positive person even when he was diagnosed with cancer, remembers Avik Mukhopadhayay. When a cartoon featuring Mamata Banerjee raked up a mighty big storm in 2012, it found a place on Bhattacharya's shelf too. "We've never had a funnier government," he had then said in an interview.

"He has always had a really large following among the youth," says Mukherjee, suggesting his fierce, anti-establishment persona could have something to do with the pull he has. But Bhattacharya was always wary of being put on a pedestal. Even his Fyatarus, he believed, weren't fighting for recognition, but "reorganisation" so that they could live in harmony.

In Lubdhak, Bhattacharya's canine protagonists not only focus on overcoming the oppressor, but also rejecting them. And these underdogs turned heroes were all dreamt of by a rebel who spent hours seated by the window in his compact ground floor apartment in Kolkata, watching the canine inhabitants of the society, and how much they had in common with man.

)