To the lay public, Vivan Sundaram is better associated with his fortuitous DNA, the nephew of one of India's earliest modern painters, the irrepressible Amrita Sher-Gil, whose legacy has been bound indelibly with his own. Considered a significant painter himself at a time of the triumph of high modernism in the country, he is also one of its few intellectual faces, having run experiments and workshops in the Seventies and Eighties (inviting artists and critics to his and curator spouse Geeta Kapur's cottage in Kasauli) before giving it up to emerge among the rare modernists who crossed the bridge to embrace a more contemporary trope - not tepidly, as several of his peers have somewhat timidly done for the sake of form, but unhesitantly and completely.

In recent times, thus, his interest has been driven by societal issues, popular culture and the desire to be provocative, the latter not in a superfluous manner meant to draw attention to himself but with the serious intent of examining our reactions and relationships with the world around us. In making up a city of trash, he heightened our ability to grasp with serious concerns. Found objects turned into fashion for his Gakawaka take on fashion. The Kochi biennale had him visit a port of the past - Muziris - and invest his archaeological findings in a thought-provoking assemblage that brought together commerce and melting points on the global highways of ancient trade.

And yet, as an artist who has stayed largely outside the temptations of the market, his is a fascinating career. His aunt never quite enjoyed her success in her lifetime, drawing critical acclaim but not, alas, commercial success, the result, no doubt, of a tragically young life. But Sundaram seems to disdain the forces of the market, cocking a snook at popular practice that would have netted him a not insignificant fortune had he stuck to his promise as a painter instead of abandoning it to the tricky world of installations. In abjuring that lure of lucre, he has taken a position outside the ambit of the galleries that tend to view such eccentric behaviour as unworthy of their interest and support, the artist only as good as the sales at his previous outing.

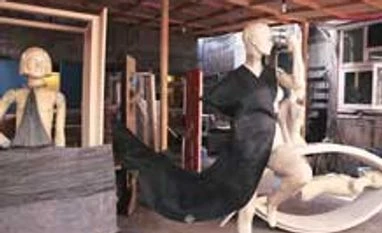

In POSTMORTEM (After Gakawaka), Sundaram has focused his - and our - attention on mannequins, a familiar sight with their androgynous faces and desexualised bodies, promiscuous models for a lascivious, image-hungry public who lap them up. The politics of fashion and anatomy come together in an adoration of limbs - a mass hypnotism of the sum of one's parts. Lights, shadows and sounds lend a dimension to the installations that emphasise the alienation of the individual, the atrophy of individuality. Using perverse humour, irony and a cruel wit, Sundaram jolts us yet again into thinking about the pervasion of an urban consciousness that eliminates the ability to think for oneself, a Stepford Wives redux that ought to be alarming. His confidence in steering his own direction allows him the freedom to cut that gash in a society where it bleeds not blood but a stream of banal consciousness.

You’ve reached your limit of {{free_limit}} free articles this month.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

Already subscribed? Log in

Subscribe to read the full story →

Smart Quarterly

₹900

3 Months

₹300/Month

Smart Essential

₹2,700

1 Year

₹225/Month

Super Saver

₹3,900

2 Years

₹162/Month

Renews automatically, cancel anytime

Here’s what’s included in our digital subscription plans

Exclusive premium stories online

Over 30 premium stories daily, handpicked by our editors

Complimentary Access to The New York Times

News, Games, Cooking, Audio, Wirecutter & The Athletic

Business Standard Epaper

Digital replica of our daily newspaper — with options to read, save, and share

Curated Newsletters

Insights on markets, finance, politics, tech, and more delivered to your inbox

Market Analysis & Investment Insights

In-depth market analysis & insights with access to The Smart Investor

Archives

Repository of articles and publications dating back to 1997

Ad-free Reading

Uninterrupted reading experience with no advertisements

Seamless Access Across All Devices

Access Business Standard across devices — mobile, tablet, or PC, via web or app

)