One of the critical elements in the struggle for freedom was forging a national identity in a country riven by language, consisting of over 500 princely states and Crown-administered provinces. From reformists and philosophers to writers, poets and politicians, they struggled to find a common, unifying cause in a country that was culturally knit together without the perspective of a unified whole. It was into this chasm that the self-taught artist Raja Ravi Varma stepped in to give India an iconography for its gods, goddesses, historical heroes and mythological heroines, leading to the creation of a pan-national image to which anyone could lay claim. This effort would have been in vain, however, were it not for a colour printing press he acquired, soon churning out these images to sell in bazaars and around temples. The prints became a rage, and the Himachali, the Maharashtrian and the Bengali were quick to take them home as icons for both their puja rooms and their living rooms.

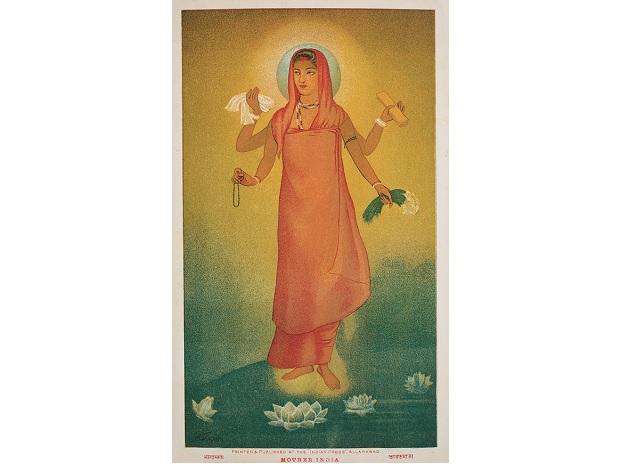

The popular nationalistic upsurge led to Abanindranath Tagore rejecting his training in Western art practice in search for one that was more indigenous, thereby laying the roots of what came to be known as the Bengal “School”. His subjects came from India’s cultural moorings, but most importantly, his painting of Bharat Mata — an iconocisation of the country as motherland — became a unifying image for the freedom fighters of the time. The demand for freedom went beyond provincialities to embrace all of India.

Gandhi himself was visualised by Nandalal Bose as the staff-bearing Mahatma on the Dandi March which went on to become a celebrated print, and came to be associated with him in popular perception. Photography provided images of the national leaders as inexpensive prints that were rendered as posters, calendars and labels, furthering their identity with the cause of independence.

Nor was art provided less than its deserving mantle in the new republic. The viceregal palace had murals painted by European and Indian artists in the Western tradition, but the circular walls of Parliament House were painted in the manner of murals illustrating scenes and episodes from history and mythology, forging the idea of the nation through its culture, even though parliamentarians rarely tarry to admire these works, being as unfamiliar with art as the average — alas! — Indian.

The Constitution, too, was handed to Nandalal Bose to illustrate, and he put together a team of artists for the task. While he and some artists were responsible for painting historical episodes, others took on the responsibility of creating decorative borders. Alas, the citizens of the republic it serves rarely see or take pride in facsimile editions of the Constitution. That the visualisation of a national identity is built into the very foundations of independent, republic India is a lesson we would all do well to remember. Kishore Singh is a Delhi-based writer and art critic. These views are personal and do not reflect those of the organisation with which he is associated

One subscription. Two world-class reads.

Already subscribed? Log in

Subscribe to read the full story →

Smart Quarterly

₹900

3 Months

₹300/Month

Smart Essential

₹2,700

1 Year

₹225/Month

Super Saver

₹3,900

2 Years

₹162/Month

Renews automatically, cancel anytime

Here’s what’s included in our digital subscription plans

Access to Exclusive Premium Stories

Over 30 subscriber-only stories daily, handpicked by our editors

Complimentary Access to The New York Times

News, Games, Cooking, Audio, Wirecutter & The Athletic

Business Standard Epaper

Digital replica of our daily newspaper — with options to read, save, and share

Curated Newsletters

Insights on markets, finance, politics, tech, and more delivered to your inbox

Market Analysis & Investment Insights

In-depth market analysis & insights with access to The Smart Investor

Archives

Repository of articles and publications dating back to 1997

Ad-free Reading

Uninterrupted reading experience with no advertisements

Seamless Access Across All Devices

Access Business Standard across devices — mobile, tablet, or PC, via web or app

)