Farhanah Mamoojee’s fascination with the long sea voyages that Indian nursemaids made to England centuries ago for work began after a short stroll from her home in London’s Hackney in 2018. A BBC documentary, historian Yasmin Khan’s A Passage to Britain — about migrations from the Indian subcontinent to Britain — had in passing mentioned an “Ayahs Home” in Mamoojee’s immediate neighbourhood which used to house travelling nannies who ended up stranded and penniless in that country in the early 1900s. Mamoojee, a gender studies graduate, became curious about this less-known piece of women’s history and Hackney lore.

“So I walked there from my flat expecting there to be some information about the home, but there was nothing at all,” she says. “And the building, although still intact with the architectural and structural style of those days, has been converted into residential apartments.”

The Ayahs’ Home is an ideal starting point for diving into the lives of these migrant women of the past. The colonial-era practice of employing Asian nannies, which rose with the establishment of the East India Company, was cemented by the 18th century and continued well into the 20th century. A servant in England cost eight times more than one in India, so the more prosperous Company employees could afford a retinue of staff. When British families took trips home to England, they brought along their family ayah or an experienced travelling nanny to look after their children onboard. According to a 1922 article in a British journal aimed at the working classes, they embodied four essential attributes: honesty, cleanliness, capability and a need to be good seafarers.

Interior of the Ayahs’ Home

Some estimates hold that between 100 and 140 such seafaring nannies visited Britain every year. A number of reasons are seen as having motivated them — financial need, affection for the children, a wish to see Britain. One Miss Antony Pareira voyaged as many as 54 times. However, having travelled thousands of miles away from their homeland unaccompanied, often a more difficult journey awaited them at the destination. With their onboard duties finished, they were commonly abandoned with little or no fare for their return.

Some knew enough to advertise their services through newspapers, while first-time travellers took to begging in the streets for a passage back. Noting that most of them lived in squalid lodging houses while seeking further employment, in the 1890s, city missionaries set up a home where they could stay until a family returning to India engaged them. The establishment became at once a placement agency, a converting station to introduce native women to Christianity, and a publicised symbol of the Empire’s charity.

The exterior of the Ayahs’ Home in Hackney, December 1921

On Mamoojee’s request, the erstwhile Ayahs’ Home building in Hackney has been shortlisted for a blue plaque, a type of inscription in London that alerts people to a place’s importance and encourages history buffs to include it in heritage walks. To drum up local interest, she organised an exhibition in early March at the Hackney Museum. She also launched an Instagram page, @ayahshome, where carefully sourced, sepia-dipped photographs are inspiring people to comment with stories about Indian nannies their families once employed. But what the researcher really wants is to find Indian descendants and acquaintances of the women themselves, as no accounts by them exist. “So far, we are only able to access the stories of the ayahs through their employers and their descendants, so it’s very difficult to get an authentic voice to give life to the realities they faced.”

One person who is pleased anytime the early subaltern immigrants are remembered for having built Britain from the bottom up is Rozina Visram. For several decades, the independent scholar was alone in researching these “nurses of ocean highways” as they were once called. Her books Ayahs, Lascars, and Princes (1986) — puzzled together from mountains of records including reels of microfilm, newspapers and contemporary writing — proved significant given the backdrop of racism South Asians experienced in the 1970s and 80s’. As a teacher in London, she was struck by the curriculum’s Anglo-centric bias. “Most people in Britain assumed that Asian migration began in the 1950s … It was believed that as ‘recent’ immigrants we had not contributed anything to Britain!” she recalls in an email.

Researcher Farhanah Mamoojee

Proving the long connection of Indians with the country was a hard slog. Working classes rarely left their own history behind and also easily slipped through official records. “There is also a gender issue: women are not seen as having played a vital role and more so for colonial working class women,” Visram observes. Her hope for a broadening of curriculums in the country was not fulfilled but she stayed with the issue and wrote Asians in Britain in 2002, another seminal work that told of the nannies’ contributions.

These travelling workers belonged mainly to South Asia, although nannies from China, known as amahs, also made similar journeys. Within India, ayahs from Madras are said to have been particularly popular, and many also came from Goa. Existing accounts, such as of the matron of the Ayahs’ Home or of employers, are typically affected by the European gaze. The common perception, Visram found, was that the ayahs were “child-like”. Publications of the time offer evidence of the prevailing supremacist and sexist attitudes. Take a 1915 advertisement in the Times of India, announcing boat departures to Europe, which reveals that while all passengers had to have a medical examination, native nannies had to present themselves four hours prior for additional “disinfection”.

In those days, the term “ayah’s baby” became synonymous for an unruly child but one Elizabeth Drummond, writing in the same paper in 1937, favourably compared the native nanny’s intuitive wisdom with the tenets of modern child psychology. The nannies, who shared deeper bonds with the children than with their mistresses, were characterised variously as patient, ignorant, fearsome, and pandering. An instance of pluck has been documented too — a woman called Minnie Green took her employers to court for hitting and underpaying her.

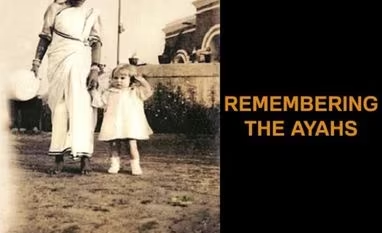

Surviving images of the women and their environments are idealised and posed too. “In the family albums of Raj families, in the ways in which photographs were staged, ayahs were seen as a symbol of status,” notes Florian Stadtler, who teaches postcolonial literature in the University of Exeter and collaborated with Visram for a British Library. “In British paintings, the ayahs were very much portrayed as picturesque. So in a sense these images really hid the fact that these were highly capable, independent women, expert sailors, engaging in multiple sea journeys and expert caregivers.”

One such photograph had first kindled the interest of sound artist and academic Cathy Lane in the subject. It depicted the women, inside the Ayahs’ Home, reading or sewing, mainly in Western dress. “Research into census and passenger records from the time showed that they were generally given Western names — ‘Ayah Susan’ or from the surname of the family that they worked for, ‘Ayah Wilson’ — and further stripped of individual identity by the recording of their place of birth as the very general ‘India’,” she says. She recently created an audio-visual piece to counter these colonial representations. The work, intending to “unmute and voice a largely silent history”, was showcased in Delhi’s Gallery Ragini during this year’s India Art Fair. She attempted this by taking sonic cues from archival material — a piano had been gifted to the home, and the ayahs had been taught certain hymns — and also recorded the voices of people born in India during the Raj.

Questions remain about the ayahs’ feelings about arrival in a new place, their idea of “home”, the sense of culture shock, their lives in India, and on how much agency or independence they exercised. Many of the research efforts are bound by the elusive search for answers to these questions. For her exhibition, Mamoojee invited young writers to compose and perform poems on what they imagined the ayahs’ experiences might have been like. Based on a documented incident of an ayah who was abandoned at Kings’ Cross with one pound in her pocket, Shruti Chauhan, a poet and radio presenter, came up with the line: “Teri mutthi me kya hai? (What do you clutch in your hand?) A £1 coin, cold and clammy.” It tells of the economic and emotional storms the seafaring nannies might have weathered.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)