The uncomplicated merits of Bollywood cinema become better apparent within the ashen, all-too-couth precincts of English cities. Three weeks after moving to London, I found myself decisively typing the words “badtameez dil” into YouTube. The song, as hoped, provided an artificial boost of energy almost as good as any over-the-counter vitamin.

For the roughly three million South Asians in the United Kingdom, many of whom have lived here for generations, films from the subcontinent serve a far more significant purpose. They offer a way to construct and carry on culture; to make a home away from home. Over time, Indians here have shaped a distinct identity rooted in both British and Asian cultures. As it followed, London came to be considered another home for Bollywood.

Six decades ago, first-generation immigrants had to hire cinemas once a week to show Hindi movies. Around the 1970s, with hopes of tapping into eager audiences, the business community started its own cinema houses. During this phase, as British writer and filmmaker Shakila Maan notes in a blog entry, “popcorn was replaced by samosas and masala chai.” That was short-lived, as the venues would eventually succumb to onslaughts from VHS tapes and more recently, multiplexes and the internet.

It was soon common to watch films at home with family and friends. Maan writes that some resourceful salesmen even rented out video machines with a package of three films for weekends, while others offered home deliveries. As such, by the 1970s, video machines owned by British Asians was on a par with video players owned by households in Japan.

Stills from Shalom Bollywood

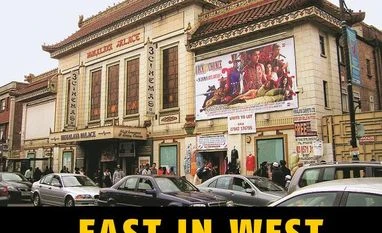

The west London borough of Ealing in particular shares a long history with South Asian cinema. At the core of Southall market stands Himalaya Palace, equal parts charming and confusing. Built in the 1920s by Englishman George Cole in the Chinese style (including a pagoda with dragon details), it was bought by an Indian who showed Bollywood films there for a decade, before shutting shop in 2010. The clothing and jewellery store owners who work in that building today have little patience for nostalgia. Owners of nearby DVD shops, while partly responsible for the iconic theatre’s decline, are more forthcoming with memories. One of them, known simply as Sunny, recalls Madhuri Dixit, Amitabh Bachchan and namesake Sunny Deol visiting it in its heyday. DVD businesses too have shrunk from as many as 30 to just three, but they still find customers in older members of the diaspora who have not kept up with online streaming.

As the main Asian shopping centre in all of England, Southall, or Little India as some call it, draws visitors from across the country. The salesman Sunny says Indian buyers prefer modern stories like Ae Dil Hai Mushkil or PK while shoppers from Pakistan or Afghanistan diasporas swear by more traditional films like Ram Leela and Devdas. While we speak, someone purchases collections of Mohammad Rafi and RD Burman songs. These stores seem stuck in the 1990s, playing old staples like “Ghoonghat ki aad se” rather than new tunes.

According to some accounts, long before Himalaya Palace, an erstwhile cinema-place named Dominion had been used by the Indian Workers Association (IWA) in the 1950s for public gatherings, live music shows and performances by Indian stars including Helen. They even hosted wrestling matches between famous wrestlers from India and local talent.

Over in east London’s Brick Lane — another major South Asian neighbourhood — what was earlier Mayfair Cinema became Naz Cinema in 1967. It screened Hindi films and once invited actors Dilip Kumar and Vyjayanthimala. Business wound down in the 1980s, as video rental and sale shops sprang up all over the neighbourhood. One exclusively Asian cinema remains active in East Ham — “Boleyn”, which was started in 1995. The modest art deco venue has two screens showing a mix of Hindi and regional language movies.

The films stir the interest of non-Asian audiences too; a few large chains like Cineworld and Odeon make space for big Indian and Pakistani releases, universities have well-attended Bollywood club nights, and institutions such as British Library and Victoria and Albert Museum hold discussions on these film industries.

For migrant Indians like Aastha Mantri, a professional economist who moved to London eight years ago, Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham and Jab We Met have nostalgic value. “I watch them when I haven’t been back home for a while or when I have just returned.” The movies also help connect various minority communities. In the book Transnational Childhoods, Benjamin Zeitlyn notes that Hindi dramas and Bollywood movies, which are popular in both London and Bangladesh, are able to unite Bangladeshis with other transnational South Asians.

Second- and third-generation residents familiarised themselves with Indian languages, religion, fashion, and music through film. Where Indian movies began including UK in their narratives in the 1990s, several writer-directors such as Gurinder Chadha (I’m British but…, Bend It Like Beckham) and Farrukh Dhondy (Tandoori Nights) in UK told stories about the diaspora experience from the 1980s.

Discussions on various aspects of film-viewing and filmmaking among South Asian diasporas are at the centre of this year’s ongoing UK Asian Film Festival. A documentary produced by the organisers, Memories through Cinema, uses multiple perspectives to paint a picture of how classics such as Mother India and Sholay were screened in the cinemas of Brick Lane and Southall.

The festival’s theme, as had been during its inception, is female-driven stories. Founder Pushpinder Chowdhry says she started the event 20 years ago with the intention of going beyond Bollywood and encouraging films about and by women. In UK, independent cinema is yet to capture the kind of audience that big Bollywood or classics like Satyajit Ray films from the archive enjoy. “It is a struggle to attract money, resources and interest,” observes Chowdhry.

In the festival line up is Danny Ben-Moshe’s Shalom Bollywood, which documents the contribution of Indian Jewish actresses like Sulochana, Pramila and Nadira who took on lead roles in early cinema when it was frowned upon for Hindu women to do so. Among the fiction features, Cake, a family drama from Pakistan starring Sanam Saeed and Aamina Sheikh appears promising; as does Rahat Kazmi’s Side A & Side B, in which a group of film lovers in Kashmir band together in difficult circumstances to make a movie.

Still from Village Rockstars

Another highlight will be a screening of Conrad Rooks’s Siddhartha, with Simi Garewal and Shashi Kapoor in the lead. The artful 1970s release, featuring an iconic nude scene that ruffled feathers in the Indian censor board then, is based on the Hermann Hesse novel. It traces young Siddhartha’s (Kapoor) search for meaning, which leads him to holy men and a courtesan (Garewal).

Garewal has been invited for interactions with the audience, and to pay a tribute to her late co-star. Also a special guest is Pakistani actress Mahira Khan, travelling with her 2017 film Verna. Notably, away from the subcontinent, art and artistes from India and Pakistan are able to share public space without facing heat from political quarters.

For details of the UK Asian Film Festival, which is on across venues in the UK until March 25, visit tonguesonfire.com

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)