Nemai Ghosh’s obsession with the film auteur Satyajit Ray held him in a thrall for the 25 years he tracked and photographed his every movement, and in the years since his death in 1992 Ghosh self-appointed himself his ambassador, keeping Ray’s images and memory alive. An exhibition of a selection of these photographs — Faces and Facets: Satyajit Ray in Colour — formed one of the exhibits of the Ghare Baire museum at the newly renovated Currency Building in Kolkata that Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated in January this year.

Sadly, Ghosh was missing from the audience, having had a fall that confined him to his bed. He never got to see the exhibition, and died in March, but not before putting to bed another project — a book of photographs on the artist Paresh Maity, whom he trailed assiduously all over the world, photographing him at work, or in more intimate moments, just as he had stalked Ray earlier.

It was Maity who asked to be photographed by Ghosh two decades earlier, and they struck up an unlikely friendship. Ghosh’s first calling had been theatre, and he sported the aura of an actor. Maity was from small-town Tamluk and had literally run away to found a career in art. If Ghosh’s idol was Ray, Maity had been struck by the charisma of M F Husain and channelled his inner persona to command the spotlight wherever he went — dressing meticulously for his role as artist-about-town.

For all that veneer, Maity remains an extremely committed artist. He saw, in Ghosh, an opportunity to document something that had not been done before — tracking an artist plein-air as he worked on locations on and off the beaten track, an opportunity to create mise-en-scenes in which both artist and photographer were collaborators. Together they travelled through cities and wildernesses, here in Jaisalmer, there in Kerala; to Shimla, or Santiniketan; now in Venice, then to London; beside the Thames, the Ganga or the Seine… Long trips were meticulously planned, but shorter ones were spontaneous. Early morning phone calls to the Ghosh household were usually from Maity asking Nemaida to join him on an unexpected adventure. Soon, he learned to keep a suitcase ready in anticipation of such summons.

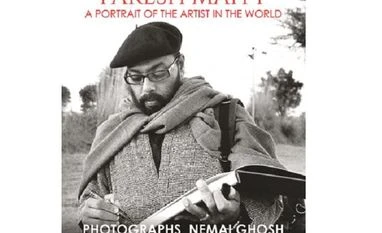

Paresh Maity: A Portrait of the Artist in the World

Photographs: Nemai Ghosh

Text: Ina Puri Publisher: Westland

Pages: 358 Price: Rs 4,999

One would expect an assignment such as this to be a vanity project, but Ghosh’s photographs — and the book — are far from such projection. There is no doubt that the subject is Maity to the exclusion of all else, but the exclusively black and white pictures succeed in capturing something entirely unique in the universe of photography — an artist’s moods and nuances, his concentration (oblivious to the swarms of people who sometimes surround him) to such an extent, you feel you are peeking into his mind and soul. “This was our journey together,” Maity told the book’s author, Ina Puri. “He took photographs while I worked. I was often unaware that he was shooting pictures of me. He was independently creating his own art.”

Puri — and this was no coincidence — had also travelled with Maity on other trips, to write about his work and those of other artists. And she had worked with Ghosh on an earlier book on artists. In a sense, their coming together was destined. Ghosh, heartbroken after losing his muse, found solace in another subject to pursue with equally dogged perseverance. But there was a difference. “In this new innings, capturing Paresh at work, Nemaida’s role became that of a director, composing and shooting to create a compelling visual narrative,” Puri writes. “He had been an integral participant in Ray’s sets, enthusiastically following his instructions, but now he was about to direct a story on his own, albeit in a different form.”

It is an ambitious book but one that holds together despite such disparate elements as Ghosh’s photographs of Maity at work, and Maity’s paintings to supplement the visual narration. Maity is a flamboyant artist, but, here, surprisingly, his paintings do not overwhelm the photographs. If Maity is subject, muse and author of the paintings, what comes through clearly is Ghosh as the genius who holds the book together. Make no mistake — this is primarily a book of photographs.

On first viewing, I wondered why the photographs had not been captioned while the paintings were. Flipping through the volume subsequently (not an easy task — it is a formidable tome of a book), it seemed of less concern. This is not a book about places; these are not travel photographs; the location and background, therefore, are incidental. What Ghosh chose to focus on — whether from a distance, or close-up, using his 50 mm, 35 mm and 85 mm lenses — was his acutely observed world of Maity: “I travelled to new cities and countries with Paresh and began working on the idea of documenting not just the painter in his familiar environment but also in unfamiliar spaces. As he randomly sat by the side of a park or a market square and painted, it appeared to me as if his entire being lightened. My modus operandi was to locate a spot where I could be unobtrusive. From that location I would start shooting. It was fantastic. I caught his hand moving fluidly on the sketch pad before him, he did not even look up to see me.” And so an “artistic collaboration” was born, one that Ghosh was able to complete, but — alas — not see to fruition.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)