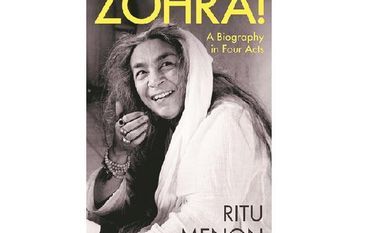

Zohra! A Biography in Four Acts

Author: Ritu Menon

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

Pages: 272

Price: Rs 599

Coping with change is a difficult skill to learn, especially if you have been used to a life of comfort. When the things that you once took for granted — and assumed to be permanent — disappear overnight, there is a sudden and inexplicable loss of meaning. You are forced to accept the new reality. You can fall apart, or you can take a breath and get yourself together to continue living.

These are lessons to learn from dancer, actor and choreographer Zohra Segal who appeared in plays such as Prithviraj Kapoor’s Deewar (1946), Madeeha Gauhar’s Ek Thi Nani (1993), BBC shows such as Doctor Who (1965), Parosi (1977), and films like V Shantaram’s Shakuntala (1943), Ken McMullen’s Partition (1987), Gurinder Chadha’s Bhaji on the Beach (1993), and Yash Chopra’s Veer-Zaara (2004).

Her life is celebrated in Ritu Menon’s book Zohra! A Biography in Four Acts. It is a loving, generous and fun-filled account from the time Zohra was born in 1912 in Saharanpur right up to her death in 2014 in Delhi at the age of 102. As a tribute to her protagonist’s career in theatre, Menon has divided the book into acts rather than sections, and scenes rather than chapters. You will also find two intermissions and a curtain call.

While it is widely known that Zohra was “born to privilege in an aristocratic, land-owning family in the heart of feudal India”, this book will also tell you about the time when shopkeepers turned up at her house in Bombay asking for the money they were owed. Her husband Kameshwar was unable to get a stable job, and her own earnings from theatre weren’t enough to take care of the family.

Menon writes, “This would upset Zohra, not only because she abhorred being indebted to anyone, but because it deeply offended her sense of herself as an honourable and honest individual, who held strongly to her principles.” Zohra was now working with Prithvi Theatres, and it meant getting accustomed to frugality. Working with Prithviraj Kapoor was different from working in Almora with Uday Shankar, her former mentor, whose company was bankrolled by “wealthy patrons”.

This book reveals that Zohra looked back at her 14 long years with Prithvi Theatres as the most fulfilling time of her life even though actors were sleeping in dormitories and having simple meals instead of travelling first class and staying in fancy hotels. She lived in Bandra, and was surrounded by a people making cinema, theatre and music — Chetan Anand, Guru Dutt, Balraj Sahni, Raj Khosla, Sahir Ludhianvi, Ali Sardar Jafri, Ravi Shankar, S D Burman and Geeta Roy (later Dutt).

Menon does an excellent job of locating Zohra in groups, movements and collectives. This will help you get a sense of her growth as a performer, and how it benefited from her interaction with other people in the arts. It will also give you an inkling of her political leanings. In Bombay, Zohra became part of the Indian Peoples’ Theatre Association and the Progressive Writers’ Association. Later, when she moved to Delhi, she worked with the Jana Natya Manch.

The period immediately after Kameshwar ended his life was particularly challenging for Zohra. She was now a single mother, and had two children to take care of. How did she make ends meet? What did she tell her children? What happened to her dreams and aspirations? Read the book to find out. Her journey is too vast for a book to capture but Menon has managed to do the task quite skilfully. Zohra’s ability to bravely confront obstacles throughout her life will certainly inspire you as you read.

“It is never easy to write a biography of a person so much in the public eye, and so beloved by it, that she becomes larger than life and her dazzling persona threatens to overshadow who she was as a person,” writes Menon, who interviewed Zohra’s children Kiran and Pavan, and many of Zohra’s colleagues. She adds, “She so completely inhabited the parts she played, the roles she assumed, the dances she danced, that performing became a way of being. How to see the face behind the mask?”

We are told that, as a young woman, Zohra had “an absolute horror of child-bearing” because her mother had died at the age of 30 “as a consequence of too many births, too close together” and so had Zohra’s father’s second wife. She was determined not to end up like them. She persuaded her father, with the help of her uncle, to let her go to Germany and pursue formal training in dance. She also took piano lessons, made friends, and travelled across Europe.

When Zohra decided to marry a Hindu man, her father was not open to the idea at first. She did not give up. When her siblings moved to Pakistan at the time of Partition, she refused to leave India. When Zohra was invited by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay to take charge of the Natya Academy for Dance and Drama, she had no experience as an administrator but she said yes to the assignment. In London, she once took on a part-time job to dress and undress actors as she needed money.

Accepting the tips was humiliating for her because of the sheltered upbringing she had enjoyed. Menon quotes Zohra, who says, “With difficulty, I put on a smiling face but let myself go in a flood of tears as soon as I reached home. All the Nawabs of Rampur and Najibabad must have turned in their graves that night.” Age also brought on ailments. Zohra had to be treated for cancer, and get cataract and knee surgery. She seems to have sought refuge in her own sense of humour.

Menon presents some delightful anecdotes that show how funny Zohra was. Zohra once wrote to Jill Williams, her agent in England, “The older and uglier and shakier I get, the more they want me in Bombay! I am thrilled to bits!” She spoke openly about her jealousy towards her sister Uzra, who was “the beauty of the family”. When they performed together in Lahore, Zohra said, “I exercised madly and set out to cultivate my charm till everyone thought I was beautiful. Plus, I could act.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)