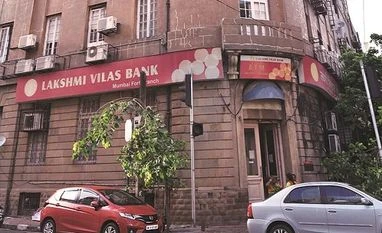

The Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) stand to delist the shares of beleaguered Lakshmi Vilas Bank (LVB) has invoked negative responses from many sections. The key losers are shareholders or investors, as the stock has been locked in the lower circuit for the fourth consecutive day. From Rs 15.7 per share last Tuesday, the stock has halved to Rs 8.10 now.

While investors’ angst is understandable, one needs to understand the possible logic behind such a move. Sample this, from -0.88 per cent tier-1 capital as on March 31, it plunged to -4.85 per cent by September 30. Hence, even a liquidity coverage ratio of over 200 per cent didn’t arrest the worsening of the bank’s net worth position.

After the September 25 boardroom battle that resulted in the ousting of seven directors, including its interim managing director and chief executive officer, there was a run on the bank. Even if that wasn’t substantial, a combination of negative net worth, deposits erosion and the bank’s precarious capital position (as talks with Clix group remained inconclusive), RBI’s decision to pull the plug on the bank seems justified.

“When the net worth has turned deep into negative, the bank’s investors’ thought of latching on to the listed entity’s value in the bourses doesn’t cut the ice,” says Nilesh Shah, MD & CEO, Envision Capital. He explains that the very nature of equity investments is that the upside and downside risks are entirely borne by equity holders.

In addition, Ananth Narayan, a banking sector expert, points out that according to liquidation norms, equity shareholders would come last in the pecking order. “Depositors and certain categories of bondholders would take precedence when a bank is liquidated,” he adds.

It is also important to distinguish between LVB’s case and other mergers orchestrated by RBI in the past. In the case of the Bank of Madura-ICICI Bank merger or of United Western Bank and IDBI Bank, a merger was invoked vide section 44A of the Banking Regulation Act (BR Act), making the amalgamation between the banks voluntary in nature. In LVB’s case, the regulator has invoked the provisions of section 45 of the BR Act, which enables RBI to apply to the central government for suspension of business by a banking company and to prepare a scheme of reconstitution or amalgamation. Global Trust Bank’s merger with Oriental Bank of Commerce and more recently YES Bank are such instances, where Section 45 of the BR Act was invoked.

A bank’s net worth position is the deciding factor whether a merger should be voluntary or forced. Section 44A comes to play when there is mismanagement and/or the regulator isn’t satisfied with the promoters’ conduct of business. But, when the net worth of a bank is under threat, as was the case with LVB, YES Bank and GTB, intervention under section 45 becomes unavoidable. GTB’s shareholders tried legal remedy, but it didn’t help them. Will LVB’s shareholders walk the same path and contest RBI’s decision, or will better sense prevail?

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)