The proportion of value destroyers shoots up to 65 per cent if information technology (IT), FMCG and pharmaceutical companies are excluded from the list. For a majority of the value destroyers (40 out of 77), borrowings now exceed their market value, putting them in a debt trap.

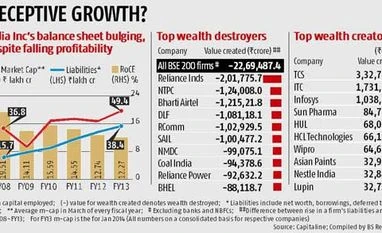

In all, since 2007-08, the 155 BSE-200 companies in the sample have together destroyed over Rs 22 lakh crore of shareholder wealth, or nearly 46 per cent of their combined market value in January 2014. The figure would shoot up by half, to nearly Rs 35 lakh crore, if the figures for IT, pharma and FMCG companies were excluded. Companies in these three sectors have together created a little over Rs 12 lakh crore worth of shareholder value in the past five years and now account for 40 per cent of the market value of all companies in our sample (see chart).

“A company’s return on capital employed (RoCE) is the sum of return on equity and return on borrowed capital, minus interest cost. So when RoCE starts falling, managements try to juice it up by increasing borrowings. But, if an economic downturn gets prolonged, like it happened after the global financial crisis of 2008, many companies find themselves in a vicious cycle of falling returns and market value and rising indebtedness,” explains Nitin Jain, head, capital markets, Edelweiss Capital.

Topping the list of companies whose market value has lagged balance-sheet expansion since March 2008 is Reliance Industries (RIL), followed by government-owned power producer NTPC, Bharti Airtel, DLF and Reliance Communications.

On the positive side, TCS is the biggest value creator, followed by ITC, Infosys, Sun Pharma (Rs 85,000 crore) and Hindustan Unilever (see league table).

In the past five years, RIL’s balance sheet (sum of shareholders’ equity and borrowings) has increased at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15.7 per cent to Rs 2.90 lakh crore at the end of March 2013, from around Rs 1.40 lakh crore in 2006-07. During this period, its market capitalisation declined over Rs 51,000 crore. In other words, RIL’s market value should have been at least Rs 2.02 lakh crore higher to justify the growth in its equity and debt during the period.

The story is the same for Bharti Airtel, the balance sheet of which quadrupled during the period as it bought more 3G and 4G spectrum in auctions and acquired Zain Africa in 2010 for over $10 billion. The company’s market capitalisation, however, declined nearly Rs 22,000 crore during the period, destroying shareholder value in the process. Government-owned Coal India is an example of a company that destroyed wealth despite being a debt-free entity. Analysts blame this on the company’s large cash reserves, which have bloated its balance sheet but earn sub-par returns. The biggest problem are companies in capital-intensive sectors like telecom, power, construction & infrastructure, metals, mining and oil & gas. These companies continue to accumulate liabilities, despite a visible decline in return ratios beginning 2007-08.

The RoCE for all 155 non-banking & financial companies in the sample declined to 12.3 per cent in 2012-13 from a high of 19.7 per cent in 2007-08 and 15.6 per cent in 2009-10. The decline has been far worse in the case of individual companies. Reliance Industries’ RoCE declined to 10.2 per cent in 2012-13 from 17.2 per cent in 2007-08, while Bharti Airtel’s RoCE fell to 7.5 per cent in 2012-13 from 24.5 per cent in 2007-08, as profitability failed to keep pace with rising balance sheet. RoCE is calculated by dividing profit before interest and taxes (PBIT) by total liabilities. Rating agencies say that a wedge between a company’s market value and the size of its balance sheet creates a financial overhang. “Market capitalisation indicates a company’s capital-raising capability and gives the management financial flexibility in tough times. If the market value falls below liabilities, it raises a red flag,” says Revati Kasture, head of research at Care Ratings. Market analysts say the only way out for many of these financially-stressed companies is to shrink balance sheets through divestments and assets sales. “A company’s enterprise value is a sum of long-term debt and market value. So, if a company cuts its debt, it pushes up market value and is value-accretive for shareholders,” adds Edelweiss’ Jain.

Others, however, caution against reading too much into the numbers, given the economic downturn. “Value destruction is common in capital-intensive sectors during an economic downturn. As long as expansion in balance sheet is accompanied by a corresponding rise in fixed assets, companies can recover their capital when economic growth and demands return,” says Devang Mehta, senior vice-president & head equity sales, Anand Rathi Financial Services.

Trouble lies for companies that utilised incremental equity and debt to fund working capital or losses. That money would be tough to recover even if growth returns, putting their shareholders at a permanent risk. Many companies in the construction, infrastructure and real estate space, besides oil-marketing PSUs, fall in this category. Their shareholders could be up for a rough ride ahead.

)