Despite the buzz around hybrid and electric, most vehicles worldwide are still powered by fossil fuels, which makes taking the calls tricky for manufacturers. That’s because on one hand car makers have to keep investing in internal combustion engine cars, while keeping an eye on the future and setting the stage for how it will overhaul, and roll out technologies when the switch does happen. This is the conundrum for Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) as it completes a decade under the Tata Group’s ownership.

While the last decade saw the Tata Motors’ subsidiary shoring up finances, marketing its strengths, and highlighting a DNA that stood for heritage, performance and prestige, JLR boss Ralf Speth’s comments on the company’s latest results point to a future decade that will reinvent JLR. “As we mark the first 10 years of Tata ownership, our focus is on shaping our future and we will continue with overproportionate investment in new vehicles, manufacturing facilities, and next generation automotive technologies in line with our autonomous electric and shared strategy.” In the past year, JLR invested half of its R&D budget in upgrading facilities and the other half in new products and tech.

It’s a delicate balance: innovate, and build scale while pushing for profit. In 2017, JLR sold around 620,000 vehicles compared to BMW’s 2.1 million vehicles, Mercedes-Benz’s 2.4 million cars and Audi’s 1.9 million cars. While it’s nowhere near the German trio, the last decade has seen impressive growth for JLR. It reported eight consecutive years of profits, jump-started sales from 252,000 units to more than double that last year, and is the UK’s largest car-maker with four plants — in Brazil, China, India and Slovakia.

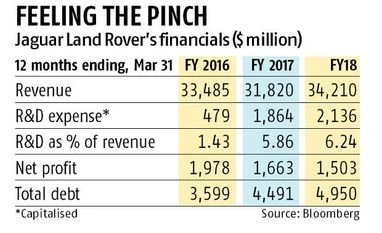

Last year, JLR reportedly invested $5.2 billion in total, and around $1.9 billion or almost 6.2 per cent of its sales in R&D. While the spend represents nearly a five-fold increase, it exerts additional pressure on a balance sheet already coping with declining profits, squeezed cash flow and increased debt (see: Feeling the pinch). The year going ahead will see the company pump in even more capital to pave the future, with $5.6 billion in total investment that includes around $2 billion in R&D.

Analysts who watch the sector say it’s not going to be an easy journey. Vikas Sehgal, global head of automotive and vice-chairman, Rothschild & Co, says, “Given the changing ecosystem, in order to maintain its positive trajectory, JLR will need to stretch managerial and financial resources to the limit as it competes with rivals in Germany, managing a fast evolving landscape of new energy vehicles, mobility and regulations.” Sehgal adds that consumer behaviour is changing, technologies are uncertain and regulatory movements across countries are not predictable.

So what’s the plan ahead? An official spokesperson with JLR says: “Our commitment is that from 2020, every new Jaguar or Land Rover will have an electrification option and we are on track.” In addition, the electric Jaguar I-Pace along with plug-in hybrid variants of the Range Rover and Range Rover Sport are currently being sold. Better late than never, but playing catch up will take time. BMW, for example, is already selling as many as 100,000 electrified vehicles.

“Basically, a company has to invest in all options available,” says Hormazd Sorabjee, Editor Autocar India. “That’s a challenge for a company which doesn’t have scale and can stretch a company thin.” While Jaguar is aware of what it will take to stay relevant, German rivals are way ahead with autonomous and electric technology. Sorabjee opines that JLR, in addition to hybridising petrol engines, will also have to move fast to fill in the gaps in its model range with new cars.

Paris-based automotive author Gautam Sen says that the silver lining for JLR is that it need not invest too much into new engines larger than two litres because electric cars generate enough power with a drive train of that size. Presently, the company makes seven Jaguars and six Land Rovers, based around three architectures plus legacy ones for F-type and XJ. The (electric) I-Pace is a bespoke architecture.

Historically, JLR’s chink in the armour has been its engineering capability, although that’s changing. It relied on a legacy deal with Ford to supply engines but it is being phased out by 2020, by when all engine production will happen in-house, JLR officials say, adding that “We have invested over £1billion in a UK engine plant and now are also manufacturing JLR designed engines in China.” The easier thing about electric vehicle production is that one can outsource production of its various parts such as batteries to suppliers such as Siemens and Electrica. The thing is it takes time. “Consider that companies like Tesla have been at it for years and years and barely have three models that are commercially ready,” Sen adds.

Thus far, JLR’s efforts have been successful at technologies such as aluminium which makes its cars light-weight but unlike steel, aluminium is less corrosive, and cannot be welded as easily. It’s much more malleable and therefore susceptible to dents that aren’t as easy to straighten out, unlike steel. Then, fibreglass and composites which are becoming staple of electric vehicles require attention combined with marketing and execution to pull it all together. It’s an area that JLR is still working on.

In part, analysts and those who track the company, question JLR’s future plans because they aren’t sure what it will stand for. Ask the company the same question and the answer from a spokesperson is that, “JLR is turning itself into an automotive technology company making cars and providing premium services — that will not change.”

Does JLR intend to push harder to accelerate volumes? The answer is “we are aiming for global profitable and sustainable growth.” Which brings the company full circle to its challenge at hand — invest aggressively, plan new products and yet churn out profits that keep the engine humming. Cats have a reputation for landing on their feet but the margin for error has gotten smaller, and what the company won’t be able to afford anymore are products that achieve anything less than success.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)