For the most part after Tata Steel outbid Brazil’s CSN for the Anglo-Dutch steel major, Tata Steel’s European business, especially the UK, has been a problem child, what with narrowing spreads between raw material and finished steel prices and cheap Chinese steel flooding the world. So much so, that in March 2016, the company under chairman Cyrus Mistry, decided to exit the UK business, in part or whole. The main reason then seemed to be the asset impairment of £2 billion between 2011 and 2016 on account of the UK business.

That decision, however, was promptly put aside after Mistry’s ouster as head of holding company Tata Sons and its key subsidiaries following a boardroom feud. Not that divestments of selective assets stopped; the speciality steels business was sold to Liberty House, Hartlepool SAW pipe mill sale was completed in 2017. And there were divestments even before Mistry’s time. But the overall philosophy over the past year has been to make the European operations more sustainable.

In the last fortnight, two of the biggest problems of the European business have been resolved; the British Steel Pension Scheme (BSPS) has been closed and the company has moved from a defined benefit scheme to a defined contribution scheme. Though as part of the separation, the BSPS has received £550 million from Tata Steel and a 33 per cent stake in Tata Steel UK, the move will de-risk the future cash flows of the company. It also paved the way for a long-pending joint venture between Tata Steel and Thyssenkrupp AG.

Tata Steel and Thyssenkrupp have signed a memorandum of understanding to create a 50:50 joint venture, Thyssenkrupp-Tata Steel.

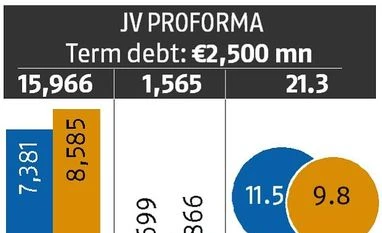

The joint venture would be a strong No. 2 flat steel maker in Europe, following ArcelorMittal, with annual shipments of about 21 million tonnes of flat steel products, turnover of ^15 billion (Rs 115,000 crore) and 48,000 employees across locations. The merger, however, could impact 4,000 jobs.

The joint venture expects ^400-600 million in synergy benefits by FY20, and Tata Steel will be transferring senior debt of ^2.5 billion carved out of Tata Steel Europe to the joint venture.

According to stockbroker Prabhudas Lilladhar, the joint venture is structurally positive for Tata Steel as its debt exposure for European operations (based on a 50 per cent economic interest) would come down 30 per cent to ^3.25 billion from the current ^4.7 billion with a higher EBITDA base of ^783 million, 12 per cent above the current EBITDA. “High dividend pay-outs from the joint venture would help service the residual debt. The joint venture would help the company to strengthen focus on India,” the Prabhudas Lilladhar note said.

“Together Thyssenkrupp Tata Steel and ArcelorMittal would control a significant size of the automotive market. It would leave just marginal players like Voestalpine,” said Malay Mukherjee, a former member of the group management board of ArcelorMittal.

But there could be challenges on the execution side. On the basis of experience, Mukherjee said, an equal joint venture was always difficult to implement.

The approvals for the deal, including from the European Commission, are expected to come through by March 2019. But Tata Steel is already busy charting out the next phase of growth.

At the press conference to announce the joint venture, Chandrasekaran had said that a deleveraged Tata Steel would be better positioned to grow faster and double capacity over the next five years, organically or inorganically.

In the press statement, Chandrasekaran had, in fact, underscored Tata Sons’ support towards this end. “Tata Sons would continue to financially support Tata Steel’s strategy for capacity expansion through organic and inorganic growth opportunities in India,” the statement said.

With total capacity of 13 million tonnes across plants in Kalinganagar and Jamshedpur, Tata Steel is the third largest steel producer in the country. JSW Steel is at the top spot with 18 million tonnes and government-owned SAIL is closing in with the completion of its modernisation and expansion programme.

SAIL, Rashtriya Ispat Nigam, Tata Steel, Essar, JSW and JSPL produce more than 50 per cent of India’s steel output. But apart from Tata Steel and JSW, it may be difficult for the rest to either go for a greenfield project or undertake a sizeable acquisition.

Both JSW and Tata Steel are geared for expansion in the domestic market, said ICRA Senior Vice-president Jayanta Ray.

JSW has announced plans to add five million tonnes capacity at Dolvi, in Maharashtra, and Tata Steel is expected to take up the second phase of expansion at Kalinganagar in the near term.

Roy also points to the opportunity the Reserve Bank-mandated insolvency process for stressed steel assets provides to players looking to increase market share without adding new capacity.

There are five companies going through the process under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code: Essar Steel, Bhushan Steel, Bhushan Power & Steel, Monnet Ispat & Energy and Electrosteel Steels. Their capacities range from 1.5 million tonnes to 10 million tonnes.

Now, it’s up to Tata Steel to decide whether it wants to continue with the aggression of its Corus strategy in the current context.

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)