Ladakh’s first trash festival called Khimsa, regular screenings by offbeat film-makers such as Manju Kak and Frederik van Oudenhoven, a group of Japanese artists creating a wall mural, a photography workshop by UK-based photographer Michael Fung — the list is long and eclectic. Known largely for its lakes, peaks and barren landscape, Ladakh is today offering a lot more than meets the eye.

The credit for this goes to the Ladakh Arts and Media Organisation (LAMO), a centre for contemporary arts that opened in Leh in 2010 and has since been pulling in lovers of art and culture from all over the world to the land of high passes.

What also adds to the art experience is LAMO’s location. The centre is housed in the newly restored and renovated Munshi and Gyaoo houses in the old town, which lies to the east of the main bazaar. Some 200 years ago, the who’s who of Leh inhabited this town which is located at the feet of the royal palace.

Towards the mid-1800s, however, the old town began to lose its eminence after the palace fell into disuse. Families moved out and the place began to take on a desolate feel. The lanes, a labyrinth of narrow alleys, decrepit mud houses, Buddhist temples, mosques and half-standing stupas, were filled with garbage. The abandoned buildings became a haven for drug peddlers and addicts.

The restoration in 2009-10 revived local interest in the region and for the first time local artists had a new, beautiful space to both present their creations and appreciate works from all over the world. By demonstrating what can be done with old, crumbling but architecturally stunning buildings, the centre is now bringing contemporary art to life in an ancient setting.

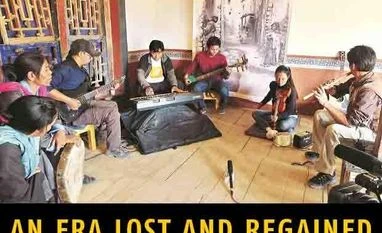

But perhaps what excites LAMO’s Executive Director Monisha Ahmed and her team the most is that the youth of the region are engaging with the centre like never before. Every time a new show or workshop is on, children from local schools, college students and youngsters from the area throng the place. “The youth lend it a vibrancy like no one else can,” says Ahmed, 52. Local pride in the area has been restored to an extent.

Visitors at the centre’s library

It all started in 2002, when John Harrison, a conservation architect who had worked on urban conservation and restoration in Lhasa and Pakistan, found himself in Leh. He began wondering what could be done to save the old town and preserve its character.

Before him, Ahmed, a textile anthropologist who had done a stint with the Mumbai chapter of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (Intach) and had been visiting Leh since 1987, had started to notice the changes in Leh.

Old buildings were being demolished and replaced by haphazard modern construction. Leh was also creaking under the weight of the thousands of tourists who had begun to visit it.

“I saw a general decline of an area I had grown to love,” says Ahmed. Above all, Ahmed was keen to see local residents take pride in their own cultural heritage and preserve and value it. In 1996, she and a friend started LAMO with no clear defined goals.

Call it luck or providence but the paths of Harrison and Ahmed soon coincided and around 2004 they began working jointly on the project to restore and renovate the Munshi and Gyaoo houses. The two houses were restored over five years by a team of over 20 people. Mud, brick and local materials were used for the restoration. The team retained as much of the original structure, design and architectural elements as possible. The idea was not to take away from the original but to highlight it.

This period also coincided with the end of the Kargil war. A couple of blockbuster Bollywood films had turned the spotlight on Ladakh.

Artworks for an exhibition on trash

As a result, money had started coming in and several agencies were willing to fund projects in the area. Intach-UK and a few others came in to fund the revival.

The restoration of the Munshi and Gyaoo houses is, however, by no means the end in itself. Leh — the old town and the main bazaar — are falling prey to the usual hazards that accompany development in an area, and the influx of tourists.

Sadly, like many Indian cities, Leh lacks an effective civil society and community action to conserve its heritage. Harrison says it has on occasion become a “local political football” with the Tibet heritage fund doing most of the work with little or no help from the local authorities.

Even today, in the mad rush to touch Tso Moriri, Tso Kar, Pangong Tso and Khardung La, the highest motorable pass in the world, the throngs that visit Leh and Ladakh tend to miss this gem. For the local residents of the region, however, the old town and its forgotten magnificence has come to life once again. It is truly an era regained.

The LAMO centre highlighted in a snapshot of Leh

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)