Punjabi-ness is hardly an ideology, nor even a way of life. But an internet search leads to breathless evidence of why it’s “awesome to be Punjabi”, how Punjabis are the “most fun people” and why “everyone should have a Punjabi friend”. Moving in the “right” circles gets you invited to lavish Punjabi weddings where you can feast on butter chicken and dance the bhangra to the beats of the dholwala while consuming a copious number of Patiala pegs from sharab di gaddi even after the bar shuts. If you care to hop in for a gedi (drive), the customised SUVs and sedans fitted with amplifier, woofers and tinted windows, and armed with more alcohol and a baseball bat or a hockey stick (just in case), are ready for “car-o-bar”. Punjabis are a loud and hospitable bunch of “Happys” and “Luckys” who celebrate life like there’s no tomorrow. Such are the clichés that are presented ad nauseam through films, songs and popular culture, so much so that it’s impossible to separate truth from stereotype.

It is said that the most accurate representation of a culture is through its arts. So when a Delhi club bursting at the seams last New Year’s Eve decided to play Punjabi singer Mankirt Aulakh’s song “Badnam”, the ones stuck in long queues broke into a dance on the roads and the bouncers had to step out for crowd control.

Sharry Mann in the video of his song ‘3 Peg’

The music video of that song has over 168 million views on YouTube and, till last month, the song was averaging four times an hour on Delhi’s popular radio channels. The video shows a skinny boy abusing his way though his teenage years and dreaming about hanging out with gangsters, brandishing a pistol and impressing women about the brawls that come his way. Aulakh’s other popular songs include “Jail” and “Gangland”, which total over 100 million views on YouTube. Critics have been quick to translate the lyrics and post them along with screenshots of beefy men sporting guns of different sizes and homogenously badass casts of face. Other habitual musical offenders were also caught in this whirlwind of criticism.

Guru Randhawa during the shooting of his song, ‘High Rated Gabru’

The Congress government in Punjab, which rode to victory last year with a promise to check the influence of drugs on its youths, swiftly assembled a team headed by Deputy Chief Minister Navjot Singh Sidhu, called the Punjab Sabhyacharak Committee, to check not just the “glorification of drugs and guns” but also “obscenity and vulgarity”. The government action has inadvertently opened a pandora’s box of problems that plague Punjab.

Violence, like love and heartbreak, has been a recurring theme in the Punjabi music of the last two decades. If the government begins to censor the artistes, it risks taking down the whole industry. From Babbu Maan’s “Kabza”, released a decade ago, which talks about seizing farm lands with the might of weapons, to Diljit Dosanjh and Honey Singh’s “Goliyaan” in 2013, which says friends in Punjab love to fire guns, to Sidhu Moose Wala’s “So High” released this year about Punjabi gangs in Canada, the list of songs features almost every popular singer, music producer, rap artist and actor from Punjab.

The state government’s action conforms to the argument that such lyrics negatively impact our society. “But it’s a chicken-and-egg problem,” as Atharva Baluja, a Punjabi film director based in Chandigarh, points out. He believes that criticising musicians will only further alienate them rather than attack the problem at its roots.

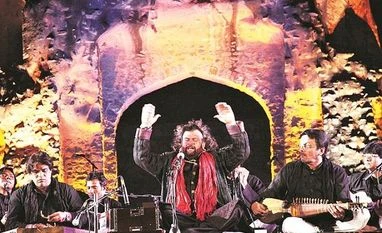

Hans Raj Hans performing at Jahan-e-Khusrau in Delhi

Singer Tochi Raina, who has many Bollywood songs to his name, such as “Saibo” from the movie Shor in the City and “Gal Mitthi Mitthi” from Aisha, says the current crop of deplorable lyrics have created the need for a censor board. “Lyrics like these do not represent any culture,” he says.

Baluja, who also runs a post-production studio in Chandigarh, has worked with many young musicians, including the 24-year-old music director behind Aulakh’s “Badnam” and “Gangland” who goes by the name of DJ Flow. “Over the years, Punjabi music has evolved with people’s tastes,” says Baluja. He says the aggressive lyrics were in great demand a decade ago and have started a trend ever since. “New musicians have also adapted themselves to jump on to the bandwagon,” says Baluja.

Rabbi Shergill at a concert

Living in Punjab, it’s difficult to escape the swagger and braggadocio. As a teenager in Ludhiana, I had to sidestep arguments too many times to count to avoid confrontation with 20-year-olds, brimming with “influence”, hot blood and machismo. The one time I misread the threat-level, a man pulled a gun on me in a park. Fortunately for me, he didn’t use it and I lived to tell this tale. I was advised against reporting him and I saw him many times in the neighbourhood before I left the city for good. Singer Parmish Verma was less lucky. He was recently shot at in Mohali, near Chandigarh, allegedly by a gangster who proudly posted a picture of himself with a gun and boasted about the attack on social media.

There can be no pussyfooting about Punjab’s gun culture. But the music is a consequence, rather than the cause, of a much larger problem that envelops it. An estimated 16.6 per cent of the youth (between the ages of 18 and 29) is unemployed in the state, against an India average of 10.2 per cent, claims an IndiaSpend report. Punjab’s economy is largely dependent on agriculture, yet it ranks eighth in rural unemployment in the country. According to the Punjab Opioid Dependence Survey, 76 per cent of the 230,000 people dependent on opioids are between the ages of 18 and 35.

Mankirt Aulakh (right) with Parmish Verma

Punjab has a minuscule service sector concentrated mostly in Chandigarh. “Thousands of migrant labourers from neighbouring Uttar Pradesh and Bihar pour into Punjab every year. There are a lot of farm hands. So what’s left for the next generation of wealthy landowners to do?” asks Amandeep Sandhu, author of Sepia Leaves and Roll of Honour, who’s writing his third book on Punjab.

Punjab’s fiery tracks and versions of rap music are often cited as obviously reminiscent of the gangsta rap of African-American culture. But unlike in the West, this genre of Punjabi music did not spring from ghettos and bear no historical weight of struggle and centuries of oppression. “Yet, the theme of revenge and violence over land ownership has been significant in Punjabi music,” says Nirupama Dutt, journalist, Punjabi poet and author.

The felt class superiority of the Jatt, a dominant and affluent caste in Punjab, has influenced the current crop of musicians. Jatts form the majority of Punjabi music artistes, dominate political affairs and wield considerable influence in the Gurdwara Prabandhak Committees.

“There’s a very clear caste divide that reflects in the music,” says Dutt. Her book dealt with the worst of this caste divide. The Ballad of Bant Singh is the story of the Dalit icon, a farm labourer and activist who lost two arms and a leg in a brutal attack in 2006 for protesting against the gang-rape of his minor daughter by upper-caste men.

The term “Jatt” has become virtually obligatory — even non-Jatt musicians continue to write and sing praises of their way of life. “Jatt di pasand” (choice), “Jatt di zameen” (land), “Jatt di anakh” (ego), “Jattan di yaariyan” (friendship) are all borrowed from popular Punjabi songs. Almost two in every three popular Punjabi songs call the protagonist Jatt and the rest of the lyrics stoke his overweening ego. “The music reflects the bias in our society,” says veteran musician Shubha Mudgal. “It’s frightening.”

A photo uploaded by Sidhu Moose Wala on Facebook

“But why the cringe-inducing apeing of the Jatt gangsta vibe?” demands Rabbi Shergill, whose Punjabi rock infused with lyrical literature is the alternative Punjabi music of the decade. The domination of Jatt-theme music, claims director Baluja, is slowly fading. Shergill describes the strutting aggression as manifesting “the last gasp of the dying”.

Ironically, the new hugely popular breakaway bandwagon is also led by Jatt music artistes, who focus on the good old themes of love, romance and relationships. “High Rated Gabru” by Guru Randhawa was the third most watched YouTube video in India in 2017. While this song now has 361 million views, his new song “Lahore” with 381 million views, is set to dominate 2018. Only a little behind is Hardy Sandhu with his songs “Naah” and “Backbone” clocking over 200 million views each.

It is true that the lyrics have not been given much thought. And equally inarguable that the catchy, bass-heavy music and high-quality videos shot with exorbitant budgets have ensured success for Punjabi music. Hindi film music too, more often than not, happily corroborates popular perceptions about Punjabi culture. “Hindi films have a long history of appropriating anything that sells,” says Shergill. In his words, the present Punjabi music being produced in Bollywood is a complete “debasement of our languages” and “an overall collapse of culture”.

Musicians have long argued that they make what sells. They show a few signs of self-awareness while shrugging off a larger social responsibility. Rapper Honey Singh in a 2013 interview to India Today said that his rap on Bhagat Singh was a flop and that he was producing what was asked of him. Diljit Dosanjh has also said that he doesn’t make songs for himself yet. Both have made deep inroads into Bollywood.

Popular playback and Sufi singer Kailash Kher says Bollywood misrepresents Punjabi music to an outside audience. “Sometimes one has to sing certain songs to stay in the business,” he says.

Punjab continues to produce powerful voices. Among the singers Kher refers to include Kanwar Grewal, who performs at Sufi and classical music events around the world, and Satinder Sartaj whose single “Sai” is highly discussed in Punjabi religious circles.

Sufi singer Hans Raj Hans says Punjabi music is about love not war and has no space for violence and misogyny. While the music should strive to be entertaining, he says, "We must not forget our own face by taking on other guises."

Gurdas Maan in the ’70s had begun singing Punjabi folk songs on his dafli (tambourine), which eventually became part of his identity. Growing up in Punjab at the time, many like my mother were blissfully lost in the verses of Shiv Kumar Batalvi, Waris Shah, Bulleh Shah, Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Amrita Pritam. She tells me how she would hurriedly note down the lyrics when her favourite songs would play on the radio. Sometimes we go through her diary together.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)