"If you ask me, my ideal would be the society based on liberty, equality and fraternity. An ideal society should be mobile and full of channels of conveying a change taking place in one part to other parts," – Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar.

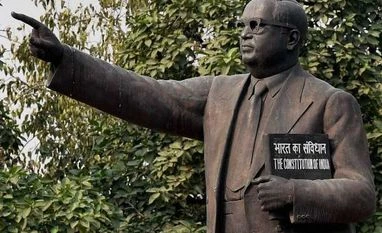

Born on April 14, 1891, Babasaheb Ambedkar, best known for his role in framing the Constitution of the Republic of India, was an eminent jurist and anti-caste crusader.

Ambedkar's legacy has left a lasting impact on India as a nation, but that legacy is rapidly becoming a site for pitched political battles as parties across the ideological spectrum seek to appropriate it for their own ends.

On Thursday, his 125th birth anniversary, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party and the Congress will take part in several events to celebrate the occasion.

PM Modi is set to address a rally at Ambedkar's birthplace in Mhow, Madhya Pradesh, to launch his government’s 10-day Gram Uday se Bharat Uday Abhiyan or village self-governance campaign.

Not to be out done by his political nemesis, Congress vice president Rahul Gandhi addressed a public rally in Nagpur on Monday to mark the culmination of the party’s year-long series of events to mark Ambedkar's 125th birth anniversary.

More From This Section

The battle, which saw a sudden escalation of hostilities after the suicide of Dalit student Rohith Vemula earlier this year, is intensifying as the 2017 Assembly polls in the extremely crucial and caste-sensitive state of Uttar Pradesh draw near.

We take a closer look at Ambedkar’s views on multiple issues that gripped his fecund mind.

Ambedkar vs Gandhi on caste:

Ambedkar's writings shed light on the formative experiences which shaped the man who would go on to become the biggest symbol of hope for India's long- and still-suffering Dalits and other backward castes.

In his reminiscences, written in his own handwriting and edited for classroom use by Professor Frances W Pritchett of Columbia University, Ambedkar said: "While in the school I knew that children of the touchable classes, when they felt thirsty, could go out to the water tap, open it, and quench their thirst. All that was necessary was the permission of the teacher. But my position was separate. I could not touch the tap; and unless it was opened for it by a touchable person, it was not possible for me to quench my thirst. In my case the permission of the teacher was not enough. The presence of the school peon was necessary, for he was the only person whom the class teacher could use for such a purpose. If the peon was not available, I had to go without water. The situation can be summed up in the statement — no peon, no water."

In one of his works in the weekly Harijan, Mhatama Gandhi wrote: "Dr. Ambedkar is bitter. He has every reason to feel so. He has received a liberal education. He has more than the talents of the average educated Indian. Outside India he is received with honour and affection, but, in India, among Hindus, at every step he is reminded that he is one of the out-castes of Hindu society. It is nothing to his shame, for, he has done no wrong to Hindu Society."

However, this same piece illustrated one of the fundamental differences between Ambedkar's approach to the caste issue and that of Gandhi.

While Ambedkar advocated the complete removal of the very notion of caste, Gandhi focused exclusively on the issue of "untouchability" and argued that caste distinctions themselves didn't need to be removed.

Gandhi wrote, "It is as wrong to destroy caste because of the out-caste, as it would be to destroy a body because of an ugly growth in it, or of a crop because of the weeds. The outcaste-ness, in the sense we understand it, has, therefore, to be destroyed altogether. It is an excess to be removed, if the whole system is not to perish. Untouchability is the product, therefore, not of the caste system, but of the distinction of high and low that has crept into Hinduism and is corroding it. The attach on untouchability is thus an attach upon this high-and-low-ness. The moment untouchability goes, the caste system itself will be purified, that is to say, according to my dream, it will resolve itself into the true Varnadharma, the four divisions of society, each complementary of the other and none inferior or superior to any other, each as necessary for the whole body of Hinduism as any other."

Role in framing the Constitution:

“What a steam-roller intellect he brought to bear upon this magnificial task, irresistible, indomitable, unconquerable,” is how one senior Congress leader and contemporary of Ambedkar described his role in framing the Constitution. (freepressjournal.in)

Ambedkar was invited by the Congress-led government to take up the job of the nation's first law minister. After he accepted the ministerial post, Ambedkar was also appointed as the chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee.

His views about the reforms needed in the Indian society were on display during the debates in the Constituent Assembly.

He mooted the need for a civil code which would be removed from religious influences.

Speaking on the matter, he said (outlookindia.com): "I personally do not understand why religion should be given this vast, expansive jurisdiction, so as to cover the whole of life and to prevent the legislature from encroaching upon that field. After all, what are we having this liberty for? We are having this liberty in order to reform our social system, which is so full of inequities, discriminations and other things, which conflict with our fundamental rights."

While Ambedkar's idea of a uniform civil code only found mention in the Constitution as a directive principle, the merit of the argument has ensured that it finds its fair share of supporters even today.

Ambedkar had also made clear his opposition to Article 370 of the Constitution, which grants special status to the state of Jammu and Kashmir. He was equally opposed to the idea of granting special status to caste. (ambedkar.org)

)