Alone in a makeup room of Filmalaya Studios, Balraj Sahni’s hands were shaking over the Remington typewriter he liked to carry everywhere. To his son, then a college student who had just walked in to get a cheque signed by his father, he appeared to be in an uncharacteristically foul mood: “I wondered if somebody had hurt him. He had not been drinking the night before.” As the actor got up — still trembling — and the son offered to steady him, he barked: “Haath kya laga raha hai? (Keep your hands off me).” It became clear later, when he was called to shoot, that this had been in preparation for a scene in which the senior Sahni’s character was inebriated and upset.

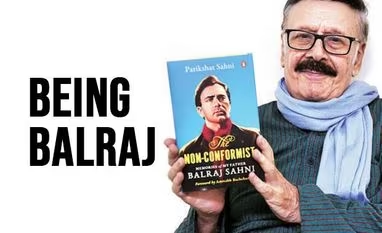

Parikshat Sahni recalls the episode in his own makeup room on the set of a daily soap. The door reads dada ji, or grandfather, a type of patriarchal character he has played over and over recently in films and on television. The 75-year-old’s gait is slow but once settled on a cot, he performs anecdotes while telling them. Unlike his father, however, he swiftly snaps out of an emotional bit to ask about a tea he had ordered. For a year and a half now, he says, he has called to mind the life and philosophy of the star of such films as Kabuliwala (1961) and Anuradha (1960). A resulting book, The Non-Conformist: Memories of My Father Balraj Sahni, will release in September.

That part of a drunk man was not a big one but Balraj Sahni would quote Konstantin Stanislavsky, saying, “There are no small parts, only small actors.” The Russian theatre veteran’s system for actors, known today simply as “method” acting, was his guide. In particular, it is said he subscribed to the theory of “emotion memory” in which actors must bring to mind something that happened in their own past and apply those feelings in the present moment. He is easily among Indian cinema’s most important actors for bringing verisimilitude to Hindi screens early on, for mellowing Hindi melodramas like Bhabhi (1957) and Waqt (1965).

While the new book is being marketed as the first-ever biography of the artiste, other writers have in the past covered various aspects of his life. Balraj’s younger brother Bhisham, Hindi author and actor, wrote a memoir about their relationship, from which Parikshat Sahni says he has drawn for his manuscript. “His understanding of my Dad was way ahead of mine. (The brothers) were poles apart physically but mentally they were one.” The two were active members of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), the cultural arm of the Communist Party of India. Bhisham Sahni’s daughter, Kalpana, too, co-wrote a book with CPI leader P C Joshi about the duo’s contributions to political theatre.

Although best known as a film actor, Balraj Sahni was a man of letters, with love for writing and theatre. He wrote in English, Hindi and later, having fitted his beloved Remington with Gurmukhi keys. His autobiography, frank and randomly ordered, has notes on pivotal experiences on and off screen but not much about his family. Born in Rawalpindi in 1913, the actor’s youth coincided with the rise of cinema, and he was fascinated by that art rather than the family’s clothing business. Having taught in Santiniketan for some years, he and his wife Damayanti, also an aspiring actor, were acquainted with other artistes. Work as BBC announcers took them to London, where watching Russian films in cinema-houses fuelled an interest in Soviet art and Marxism.

“He was essentially a theatre man,” says his son. “He believed that was the actor’s medium.” The idea of “people’s theatre” had interested the Sahnis in London and on returning they looked up similar efforts. By way of the IPTA, Balraj Sahni met Khwaja Ahmad Abbas and starred in Dharti ke Lal (1946), landed a part in Bimal Roy’s masterpiece Do Bigha Zamin (1953), and starred in the Indo-Soviet film Pardesi (1957). Nikolai Gogol’s Inspector General and plays about Ghalib were staged, among others. Young Parikshat would sometimes be asked to stand in for absent actors.

Parikshat Sahni (right) with his half-sister Sanober (extreme left), sister Shabnam and father Balraj Sahni

Post-Independence, the actor moved away from the CPI and gravitated towards Jawaharlal Nehru, although he had written a successful play Jadoo Ki Kursi that mocked the new prime minister’s policies. Out of regret, he burnt all copies of it later. In that period of inner ideological strife, however, he was arrested for participating in a communist demonstration. He left the party upon release. Still, curiosity pushed his son, who had grown up around talk about the greatness of the Soviet system, to study in Russia. “It was a gigantic machine that could take on the US and send people to space. But I could make out there was lack of freedom, everything was regimented.” The book includes pictures from their meetings there and various family holidays.

If Balraj Sahni’s performances have a distinct and spacious interior, it is because they were born of lived pains. The Sahnis had been displaced by Partition. Until the 1950s, when he was in his late 30s, he had struggled for steady work as an actor. In 1947, he lost his wife who was only 28. Years later, while returning from shooting a heart-wrenching moment in Aulad (1954) — where a poor man who has lost his wife has his son taken away from him by his master — he had urgently turned the vehicle back to the studio. The studio had closed and many in the crew wanted to hit the bottle but they assembled for another take, his son observes. The claps from his previous attempt turned to tears on this occasion. “He said this time while giving the shot he was thinking of me, and how he had felt when my mother died.”

Personal tragedy would inform another important role of his career, M S Sathyu’s Garm Hava (1973) about the predicament of a Muslim businessman who chose to remain in India after Partition. He filmed a sequence, where the protagonist finds his daughter has ended her life, not long after his own daughter died similarly. That was my sister Shabnam for him, says Parikshat. Balraj Sahni is quoted as having said to Joshi: “It is not easy to have lost both Damayanti and Shabnam.” Balraj died in 1973. He was survived by his son, his second wife Santosh, and daughter Sanober.

“He was only 59, very young.” In writing the book, Parikshat Sahni had to “sort out my relationship with my Dad, which was somewhat stormy in the early days because I never lived with him”. His childhood was spent with his grandparents and uncle. A year before his death, Balraj Sahni delivered a momentous convocation speech at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, urging people to give up borrowed colonial thought and truly free themselves. It was honest and introspective in ways that can be instructive for actors of today. “He was an extraordinary man,” reflects his son. “I say man, not actor. It is one thing to be a good actor, and another to be a good man.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)