It was in Indonesia that the penny dropped. After having worked, taught and volunteered for a few years in the United States, Neil D’Souza found himself in Sumatara in the year 2011 – working in schools in the tsunami-hit areas.

It was here that D’Souza realised that while all the content in the world was available and mostly free for students to use, they couldn’t access it due to very poor connectivity. Internet access was highly erratic, if not missing.

From Indonesia, D’Souza happened to land up in Mongolia and it was here that D’Souza started working on a solution to his problem. Travelling by train to China to find appropriate parts to build his device, his engineering degrees from Mumbai, North Carolina and then experience with Cisco stood him in good stead while he developed a product he thought could solve this problem: How to offer connectivity to students in areas where it was hard or impossible to find one.

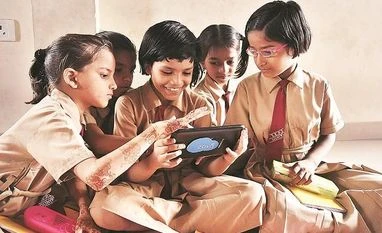

After a few months, he had a product ¨Class Cloud¨ to offer schools, teachers and NGOs who need to impart knowledge to students but had very little to do it with. Class Cloud provides Internet connectivity but works almost like a mini-computer for the user, allowing student to do much more with it than a regular Internet service. Class Cloud allows the students to learn at their own pace with the help of the Internet and the technology developed is especially to promote such individualised learning.

To D’Souza’s surprise, there were quite a few takers for his product. From local schools and orphanages to the World Bank, many seemed to find a need for the Class Cloud and his product was being adopted and experimented with widely. After nine months in Mongolia, D’Souza returned home to India and set up base in Mumbai. Why not sell Class Cloud to Indian schools spread in the remote parts of India where Internet is virtually non-existent and where personalised learning is largely unheard of.

That’s when D’Souza realised that India is no piece of cake. What works for the rest of the world may or may not work in India. He had begun by offering his product to ‘budget private schools’ in India and soon had the usual realisation that businesses and marketeers from around the world soon have – things you can take for granted anywhere else can often fail to work in this unique country.

Slowly, he realised that his audience target was wrong. There are three primary categories of ’budget private schools’ in India. The monthly fee ranges from Rs 100-400, Rs 400-1,200 and Rs 1,200-2,500. Zaya, the co promoted by D’Souza, made the initial mistake of trying to target the middle segment of Rs 400-1200 fee bracket, only to find it is a near impossible segment to crack. First, very few care about providing any kind of quality. Second, the concept of personalised learning echoes only when a school leader is himself educated and not a businessman trying to make a profit. And lastly, even if you managed to sell to a customer, extracting payments was another challenge. “At a company level, obtaining payments for services provided became more of a “fire-fighting exercise”, explains D’Souza.

So starting 2018, Zaya changed track and is now focusing on the upper budget private schools (Rs 1,200-2,500) segment. It is this segment that is usually open to trying serious quality initiatives after they exhausted all the marketing gimmicky stuff like Smartboards. D’Souza feels that he has now found the right audience. So far, 140 schools have signed up. In the personalised learning space, Zaya is working with 250 schools. Its programme to impart English - English Duniya ¨C is being deployed in 450 schools so far. Projects are running in Uttarakhand, Maharashtra and Gujarat.

What has been more heartening is that the company is seeing a lot more pull for its product from US and other markets where they have leapfrogged the traditional school systems.

The US has of late emerged as one of the bigger markets outside India for Zaya. A pilot project is being run with around 20 micro schools that typically have 40-50 students in a multi class and multi age format and use personalised learning to teach the students. The schools are spread around Arizona and Texas. In addition, their products are being experimented with in Zambia, Nigeria and Indonesia, among others. The last round of funding raised by the company was in 2014. D’Souza says that he consistently had a “burst of customers” who have kept them at break even point at any stage. Last year, the company made a modest profit. A second round of funding may be on the cards after 18-20 months. D’Souza says that he sees growth coming from “English Duniya” in India but while that may sell widely, it is unlikely to bring in a big the chuck of revenue. Licensing of the products will generate a larger revenue.

Akshay Saxena, founder of Avanti Learning who has been watching Zaya’s growth, says that while the technology is very useful, its adoption is very hard.

“The content bundling and quality will be the differentiators,” he added. Bikramma Daulet Singh, managing director of the Central Square Foundation, says that a big challenge with servicing affordable private schools is getting more schools into the fold. Unlike the government, there’s no aggregator and hence there’s no single channel to reach all affordable private schools. “As a result, sales cycles are long, overheads are high and margins poor,” he says.

So, will India be the light at the end of the tunnel or will Zaya make its fortune elsewhere? It’s too early to answer this but either way the learnings for Zaya in India can only stand it in good stead in the future. As D’Souza sums it up : “India doesn’t allow anyone to take anything for granted at anytime.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)