It was not the first time Ashim Ahluwalia had been running late for an appointment. At Dagdi chawl, in the residence of notorious gangster Arun Gawli, which is as much an apartment as it is a shrine for various deities, a crowd had gathered. A coterie of older henchmen and younger fanboys was there to pay obeisance to the man out on parole, while a few policemen kept watch. Ahluwalia broke through this circle to join his team — actor Arjun Rampal and a producer — and took a seat. Gawli was in the midst of a conversation with them but his gaze routinely travelled sideways to Ahluwalia. Minutes later, he turned to him and snapped, “Tu recording toh nahi kar raha na? (You are not recording this, are you?)”

That was when the room realised that the indie director had not yet been formally introduced. That initial meeting also gave Ahluwalia a significant insight into the mind of the quiet mobster he was expected to bring to screen. “He is not like the proactive, strategic gangsters you see in the movies,” he observes. “It was just freaking him out that I was sitting there and he didn’t know who I was.”

Gawli’s paranoia is not entirely unfamiliar to the filmmaker. When Ahluwalia was asked by Rampal to get onboard Daddy, the title of a biopic and also Gawli’s popular nickname, he had similar reservations. The film belongs in a more mainstream space, quite detached from the esoteric realms where he typically likes to operate.

This is the Bard College-trained director’s first film made primarily for an Indian audience, and he calls it his most accessible work. Even so, by Bollywood standards, some have labelled it experimental. His last film, Miss Lovely (2014), set in a similar time exploring C-grade filmmaking in downbeat Bombay of the 1980s, had international producers. This time around, he drew up an exhaustive contract. “All the lawyers thought it was quite funny that I said I want to be involved in every department, even the poster.” He convinced Rampal to become co-producer to ensure he would have a free hand. “I come from a school where film is a director’s medium. In India it’s a star’s medium.” Rampal agreed, as he had spent nearly a year working on drafting the story himself after a producer approached him with the rights for Gawli’s story. The two collaborated to develop that script.

Where most Hindi gangster films change names and make veiled references to protect themselves and the characters on whom they are based, this is a rare occasion when a film has retained most of the original names and events. Daddy has the blessing and participation of the gangster himself, with whom the film’s makers spent time during his parole. In those short hours, Rampal would observe his posture, how he picked up a cup, or how he answered calls. The strapping actor had to make himself appear smaller to mimic Gawli. “There is a blank wall that you just cannot penetrate. He uses mystery as a weapon,” says the director. The film will attempt to draw on this nuance rather than spruce up the character.

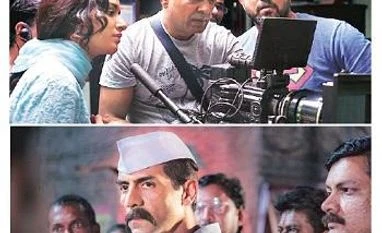

(Top) Director Apoorva Lakhia (far right) with Shraddha Kapoor on the sets of Haseena Parkar; Arjun Rampal as Arun Gawli in Daddy

Daddy may not be alone in this chase for realism. September will mark the release of another gangster film, Haseena Parkar, which tells the story of Dawood Ibrahim’s sister and was made after a year-and-a-half of interviews with her.

“My understanding of Gawli kept shifting based on who I spoke to,” says Ahluwalia, placing last orders at a Bandra café where he again arrived a little after the agreed hour. There was not much information on the Maharashtrian mobster on the internet, and news articles on him had discrepancies. Oral accounts were the most detailed, even if varied, so Ahluwalia and Rampal decided to tell the story through the points of view of six people. These will include, among others, a cop, a gang member, Gawli’s mother and his wife. There will be vantages of three women, notes the director, adding that is rare for a gangster film. The way the film’s crew sees it, Gawli has done a lot of bad things but he has also done his time.

The film spans four decades of Gawli’s dramatic rise and struggles. Gawli, a young man unemployed after the textile mill strike, had taken to organised crime in the 1970s, working together with Rama Naik and Babu Reshim in “Byculla company”. After Naik was killed by the police, he built Dagdi chawl like a fortress and ran the gang from there. Throughout the early 1990s, they were involved in a bloody war with Dawood’s gang.

“We saw a lot of gang war photographs in the newspaper, we knew a lot about Dawood’s mythology. But Gawli was always confusing,” says Ahluwalia. “He was always the guy in the kurta and topi and looked like the sweet guy.” His political ambitions starting in 2004 will also feature in the film.

Ahluwalia has played with light so that each decade looks a little different. They used a set to recreate Dagdi chawl but filmed some portions on the streets of Dongri, Agripada and Nagpada. At one point, Rampal, dressed as “Daddy” in a Rs 150-shirt picked up from Mahim, was taken to Nagpada, a Dawood territory. Ahluwalia’s team also travelled to tiny markets in Nashik to find 1980s-style printed saris and nighties. Taking actors to real spaces and making them work with non-actors — actual shooters were cast in bit parts — is typical of Ahluwalia’s immersive style of filmmaking. His Miss Lovely had begun as a documentary before he merged that research with a fictional tale.

Closely connected with Gawli’s story is that of Haseena Parkar. Gawli’s gang war with Dawood escalated when the Dagdi chawl gang shot and killed Parkar’s husband, Ibrahim. She would go on to become a feared name in the Mumbai underworld until her death in 2014, and her life is central to Apoorva Lakhia’s next film. Lakhia had been approached to make a movie on Dawood but after meeting Parkar at her well-appointed residence in Gordon Hall, Nagpada, decided to make her biopic. There were large white sofas, mattresses, and the corridors were strewn with footwear as large crowds waited to meet her and discuss their problems one by one. Parkar wanted to see a script before she agreed but Lakhia drew the line there. “I told her there would be brickbats with laurels. For some, you are a godmother and for some, a gangster.”

The sensibilities of the two films appear different, given Lakhia’s more commercial flair. He is no stranger to gangster films, having made Shootout at Lokhandwala in 2007. This time around, he has no-objection certificates to use real names of all people involved. Still, Parkar is played by mainstream actor Shraddha Kapoor, while a young, lean Ankur Bhatia plays her husband. Kapoor gained eight kilos and wore silicone prosthetics to look more like Parkar.

An accusation often levelled at Lakhia is that he glorifies criminals but he says he picks them as subjects because of the inherent drama of their lives. “(Parkar) was affected by her brother’s steps, and became what she did.” To avoid a one-sided view, he will tell the story also from the perspective of a public prosecutor.

Parkar is unique for having been implicated in 88 cases and going to court only once, the director notes. Her husband, too, was singular in running a vegetarian restaurant in Nagpada and working as a stuntman in Bollywood. She would receive payoffs for helping with numerous real estate deals. It has also been reported that one of her business interests was in negotiating overseas rights of Bollywood films, typically in the regions of Central Russia and West Asia.

Lakhia met with many individuals connected with Parkar’s investigations — her lawyer Shyam Keswani, past police commissioners, the public prosecutor, and others whom he describes as a mix of “nice and shady people”.

Bollywood has a history with the underworld. Actors and directors, including Shah Rukh Khan and Rakesh Roshan, had been reported to have received extortion calls, while some gangsters had relationships with stars. It is not clear if such links remain and to what extent. The tradition of gangster films in Bollywood includes such names as Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya and Anurag Kashyap’s Black Friday. These were fast-paced but believable. Later, with Once Upon a Time in Mumbaai and more recently Raees, such films began to wear a more sanitised, glamourous look.

Ahluwalia argues that films in the country’s south score better in this respect. “If there is a gangster film set in Madurai, then the guys look like they are from Madurai.” In contrast, he recalls a producer suggesting beauty queens for the role of Asha Gawli, the gangster’s wife. He eventually zeroed in on Aishwarya Rajesh, the actor known for the Tamil film Kaaka Muttai that won a National Award.

Research for these films is often meticulous as it relates to dangerous, influential people. “On any such project, the tougher bit is before the research — the period when you are getting acquainted with the principal players of the drama, while they, in turn, are checking your bona fides and your perseverance,” observes filmmaker Kabeer Kaushik whose Sehar and Maximum dealt with underworld crimes.

Indeed, both Ahluwalia and Lakhia said it took time to get their subjects to open up. After they were comfortable, there was sometimes the opposite problem. “(Gawli) was telling us things we really ought not to know. But you can’t betray someone’s trust because they are giving you that access,” says Ahluwalia. Parkar’s family flung open their homes including old photo albums and dressing rooms to help Lakhia’s design team. The risks of working with living or known gangsters is perhaps offset by one notable fact. As Lakhia puts it, “Gangsters want to have a movie made on them. They enjoy the fascination.”

There seems to be an allure about gangster films for the audience, too. “At the back of his mind, every man thinks he is a gangster,” says Lakhia. Ahluwalia agrees. “It is wish fulfilment. The fact is gangsters take charge in an anarchic way of a situation that is not in their control, and they have a pact of loyalty. The audience can engage with this without participating in it.”

Organised crime may have lost some steam in recent years but its appeal has far from died down. And, it may not be just men who are drawn to the idea. Some weeks after news of his film got out, Ahluwalia received a desperate call from a woman in Satara, Maharashtra. “She wanted to start a matka (gambling) den, and wanted me to hook her up with ‘Daddy’ for that.”

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)