Even after all these years, Ronaldinho still has a hypnotic hold over his audience. The thrills and spills make him football’s version of David Copperfield, just far defter. His preternatural ability allows him to turn a defender and then nutmeg him without even touching the ball, or loft a ball in the path of Diego Costa while looking in the other direction. No, not that Diego Costa, not the one with the hulking frame and the sulking ways; not the one who has just swapped the bitter cold of West London for the cheery warmth of the Spanish capital. This Diego Costa, in fact, plays for the Delhi Dragons.

This latest episode in Ronaldinho’s long list of sorcerer escapades, and his camaraderie with Costa, happened to take place at a Premier Futsal game between the Dragons and the Bengaluru Royals three nights ago. The match itself ended in a thoroughly entertaining 5-5 draw, with Paul Scholes, the Royals captain, expertly exhibiting a reckless old talent: how to pick up needless yellow cards by committing to tackles you’re never destined to win.

India is being strafed with a fair share of football these days. Premier Fustal is an obvious highlight for its heavyweight participation — Ryan Giggs, Hernan Crespo and Michel Salgado are also playing — and five-a-side football’s fast-paced entertainment. In less than two weeks, however, India will find itself at the other end of the football gamut. It will go from playing host to the old and discernibly unfit — some of them, at least — to welcoming the young and sprightly. The FIFA U-17 World Cup kicks off in New Delhi on October 6.

And, if Ronaldinho chooses to extend his Indian sojourn by a few days, he might be able to experience the tournament he would undoubtedly fondly remember. In 1997, he was a part of the Brazilian side that won its first U-17 world title — then called the World Championships — in Egypt. Just that 20 years ago, the football World Cup — of any age-group — coming to India was like expecting Arjuna Ranatunga to beat Maurice Greene over the course of 100 metres.

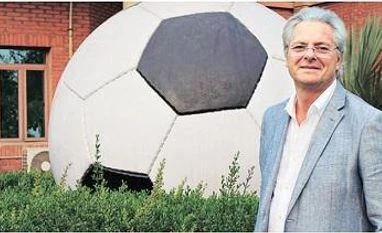

Tournament Director Javier Ceppi inspecting the Salt Lake Stadium, the venue for the final. Photo: PTI

Now that it is finally here, it would be a massive injustice to Indian football fans if the fanfare around it were dismissed as mere puffery. For a nation starved of quality international football, and one trying to foster a football culture for several decades now, this is ground zero. A new dawn.

Over the past few months, Henry Menezes, the thickly moustachioed former goalkeeper of the Indian team, has been unusually busy. Ever since he stopped putting his marvellous reflexes to use, Menezes has started applying his football brain more than ever, as a consultant, mentor, and now as the CEO of the Western Indian Football Association. “This is a huge opportunity for us as a football nation. And since it involves youngsters, it can alter the future course of Indian football,” he says.

Menezes rubbed shoulders with the likes of Carlos Valderrama, Marcel Desailly and Fernando Morientes when the trio was in Mumbai to promote the tournament earlier this month, even enjoying a kickabout. “They have great expectations. They hope to see the fans come out in big numbers and the team do well,” he says.

Mumbai has particularly been swept by the frenzy surrounding the World Cup. As a welcome gesture for teams, signs festooned with 20-odd balloons have sprung up. Over 200 flags commemorating the tournament are fluttering across the city. And, Menezes finds it impossible to conceal his joy when the D Y Patil Stadium, poised to host eight games, including one semi-final, comes up for discussion. The stadium in Navi Mumbai, occasionally used for Indian Premier League matches in the past, has undergone a serious revamp: all 45,000 seats have been replaced.

Coach Luís Norton de Matos. Photo: PTI

Almost all venues, including Kolkata’s Salt Lake Stadium and New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium, have been given a facelift, with new bucket seats and dressing rooms. The other cities that will host matches include Margao, Kochi and Guwahati.

Menezes is not alone in this optimism. Eric Benny, former player and manager of the Indian team, points to the several years the members of the U-17 team have ahead of them. “This is a phenomenal chance for India simply because the players are being exposed to the rigours of high-quality football at such a young age. These players will obviously last longer than the senior ones,” he says.

The official Twitter page of the Indian football team is a hectic — and hugely informational — place these days. It is a terribly busy time, after all. In addition to the World Cup, both the U-16 and U-18 teams are also in action; the former easily overcame Palestine earlier this week. And despite offering updates on all matches involving India, even those at the All India Football Federation (AIFF) are visibly more drawn to the fervour that the U-17 World Cup has triggered.

Over the past month, AIFF has been making efforts to get the Indian fan acquainted with members of the U-17 roster. And, any conversations with teenagers mostly throw up interesting things. The Indian team is no different: Gurmeet Singh is a fan of Gippy Grewal, the popular Punjabi musician-actor; Shubham Sarangi is inspired by Leonardo DiCaprio; and Komal Thatal — despite being an international footballer — can’t get enough of the unhealthy momos.

But this team hasn’t been shaped by the frivolities of social media. It has been moulded by physical labour spread across the past two years that have been spent preparing for what players are looking forward to as a once-in-a-lifetime occasion. Midfielder Jackson Singh believes that the side is ready to show the world what it has got. “It’s like our moment has arrived.”

Such buoyancy and a milieu of calm have taken their time coming. In January, German Nicolai Adam, the team’s coach of almost two years, was sacked after players revolted against his methods. He was accused of beating them up, and was replaced by Luís Norton de Matos, a Portuguese youth coach who played a stellar role in the development of Renato Sanches and Victor Lindelof.

Even as the careers of his two former wards are in a difficult phase — Bayern Munich has loaned out Sanches to lowly Swansea City and Jose Mourinho doesn’t fully trust Lindelof to hand him regular starts at Manchester United — Matos has brought with him much-needed solidity. “My teams are built around hard work. And, we’ve been putting in a tremendous amount of work. Mentality is key,” says the 63-year-old.

Matos has devoted substantial time in refining two historical weaknesses of any Indian team: technique and the ability to efficiently hold and pass the ball. “A lot of training exercises have been based around that. They’ve also been made a little more complicated because I want my players to think,” he says.

It would be grossly unfair to expect the Indian colts to bedazzle crowds with swift, eye-catching football. This team, after all, is built around stability — dogged and resolute are likely to make for more accurate descriptions. India’s proclivity for a measured, somewhat defensive approach is perhaps pertinently illustrated by their two more experienced players — Suresh Wangjam and captain Amarjit Kiyam — both playing in the middle of the park.

There is a reason why Kiyam was chosen as captain by his teammates when Matos last week announced a snap poll to decide who’d be leading India out against the US on October 6. Kiyam was hugely impressive and influential during India’s various exposure trips abroad, often exhibiting an unusual calm on the ball, interspersed with the odd bit of flair — just like his idol, Andres Iniesta.

“The trips to Spain and Germany really changed my outlook. It was nothing like I had seen before. That’s how I’ve grown,” he said after returning from one such exposure trip. Remarkably, Kiyam wasn’t even sure of his place in the squad till a few months ago. He is now expecting his parents to make the long trip from his village, Thoubal in Manipur, to Delhi when he pulls on the armband against the US.

Kiyam and Wangjam would do well to feed the ball to Aniket Jadhav, the striker whose strapping frame belies his 17 years of existence. Jadhav, who has represented India at various age levels, first made a mark at the 2014 edition of the FC Bayern Munich Youth Cup. Having won over Matos, Jadhav will be India’s main goal-scoring and creative threat. His likely assistant will be Sikkim-born Thatal, the diminutive winger with the beach-blonde hair. Thatal is known for his searing pace, a quality that perhaps Matos could’ve done more with in the squad.

Despite the talent, progress from a group that also includes — apart from the US — Ghana and Colombia, looks mighty difficult. Football commentator Novy Kapadia, who watched the team compete in a Brics tournament in Goa last year, warns against getting carried away by the hype. “They were decent in Goa but I don’t see them posing a serious threat to the teams they’ve been pitted against,” he says. “Their best chance of them going through is by finishing as the best third-placed side.”

The muggy weather that will welcome teams at some venues would’ve ideally played to India’s advantage, but with Ghana and Colombia both being tropical countries, that edge has been significantly mitigated.

Football writer Shaji Prabhakaran is hoping for at least a draw. “Even a decent performance against one of these teams will come as a boost.

It can give us a lot of confidence.”

Legacies in Indian sport are iffy affairs. The one spawned by the 1982 Asiad is fresh and relevant; the one conjured up by the 2010 Commonwealth Games is detestable, and ideally, shouldn’t live in the memory for long. For all its pageantry, the real challenge for the U-17 World Cup is not so much the organising, but whether it can actually set off something truly captivating in Indian football.

The infrastructure will obviously help. With 24 new training pitches and six state-of-the-art stadiums, experts say that access to better facilities will come as a boon. Over the years, despite building magnificent cricket grounds, our football stadiums have been languishing in archaic times, complete with rickety stands and appalling pitches. That is about to change, albeit in a small way.

As for the players playing in the World Cup, the AIFF would do exceedingly well not to disband this side — as is the norm with most youth teams. Keeping them together and making them play in the I-League — as the Pailan Arrows did a few years ago — seems like a brighter idea.

“The AIFF should ideally groom this group. You can phase out players and bring in some new ones along the way, but the team should be kept intact,” says Benny.

More crucially, Benny stresses on the need for European football. “A lot of these boys should be playing in Europe. That way, their tactical awareness and football acumen will change completely,” he says. “If we keep playing them in Asia, then we’re going back 10 years.”

For now, Europe seems a distant reality. But the road to getting there starts now. Costa — the Chelsea one this time — never played in the U-17 World Cup, but some of his Spanish teammates did. Much like Ronaldinho, Cesc Fabregas and David Silva announced themselves to the world at this very stage. Ten years down the line, India could definitely do with a few players in the same vein as Fabregas and Silva.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)