Breakdancing is finally emerging from the shadow of hip hop and coming into its own. It’s one of the four new events, along with skateboarding, surfing and climbing, nominated to be part of the 2024 Paris Olympics. Though it debuted at the Buenos Aires 2018 Summer Youth Olympics, it’s still a matter of considerable debate if it should be called a sport and brought to the most competitive world stage — and also if we should be debating this in India. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves here. Let’s start by getting the lingo right.

Breakdancing is a dance form, yes, but it should be called “breaking” and not breakdancing. The first reference was to differentiate the noun from the verb. And we’ll stick to the noun from here on.

The International Olympic Committee recognises it as a “dance sport” and if you hear a breaking artiste using the term breakdancing, it’s because they know how the original name is being misconstrued right from the beginning.

It’s b-boying for boys and b-girling for girls (where b stands for break). Some even call it the hip hop dance — which only reflects their lack of interest in understanding a cultural revolution, so let’s just move on.

B-girls Ami (left) and Jo

Street dance, though, is still an acceptable mistake. Because breaking started on the streets of the Bronx in New York in the late 1960s. It was hip hop’s first dance form. Popping and locking — again, two separate terms — joined soon after. There are many other styles fused together under hip hop. Remember the film Step Up? But the original form, however, continues to be widely misunderstood, especially in India.

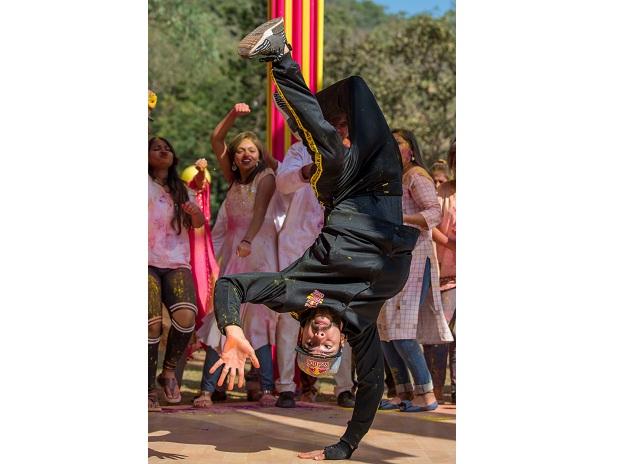

“Some people just call it stunts,” says Arif Chaudhary, who goes by the name of b-boy Flying Machine. The Mumbaikar is one of India’s top b-boys. He’s won the India cypher (read chapter) of the Red Bull BC One, the most competitive breaking championship in the world, a record three times in the last four years. Each time he won it, he went on to compete with finalists of other countries for the world championship in one-on-one battles.

That championship, by the way, will be held in Mumbai later this year. It’s not because India has the world’s best talent but because the organisers feel that breaking is picking up pace here. Nonetheless, it’s a big deal for a growing community of artistes in the country.

“When I started in 2005, there wouldn’t have been more than 25-30 b-boys in India,” says Chaudhary. “That number must be in the thousands today.” His estimate sounds about right. Red Bull BC One started in 2004. They first came to India in 2015 and restricted themselves to Mumbai, only to realise later that hundreds of contestants had come from many other cities. The following year, they also went to Delhi, Bengaluru and Kolkata. In 2017, they added Hyderabad and Jalandhar to that list.

Last week, Red Bull had to conduct extra workshops in Jalandhar because there were just too many people complaining that they couldn’t register. These training workshops, which admit about 30-40 people in one session have many more waiting in queue. And the enthusiasm is not limited to just a few cities.

Bir Radha Sherpa was practising till late night in Silchar, Assam on Thursday when I tried reaching him on the phone. The 20-year-old has become something of a local celebrity since he won the Dance Plus 3, a dance competition reality TV series, which was judged by choreographer Remo D’Souza.

“In a few years, India will be ready for the Olympics. People are really taking to it,” says D’Souza. If India does go to the Olympics, D’Souza says Sherpa will be his pick for a medal.

India will soon be ready for the Olympics. People are really taking to it: Remo D’Souza, Choreographer

Like in any other dance form, it all starts with footwork and rhythm. But there on breaking gets extremely athletic. Moves like windmills and handstands lay the foundation for the harder ones to come. Artistes at a more advanced level come to be known for their freezes and power moves, especially when they adapt them to their own style. “I was a lyrical dancer and didn’t even know what b-boying was when I started imitating it,” says Sherpa. He says he has now mixed contemporary, jazz and other forms to find his unique style. B-boying judges are suckers for originality.

But a noob is putting his body on the line every time he experiments with a hard move. The least he needs is a soft landing.

“You can find even the most seasoned b-boys practising in parks in Mumbai,” says Chaudhary. He says it’s only been about two years since he got access to a studio that has a proper mirror and a cushioned floor. “For many years, even while competing for championships, I used to practise in parks and on the streets like others,” says Chaudhary.

Indian hip hop is picking up and the success of rappers like Divine and films like Gully Boy has brought some necessary attention to the street art. Recognition is hard but money is even harder to come by for artistes in India.

While Puma and Myntra have signed Chaudhary to promote their athleisure collections, for most breaking artistes in the country it’s still the battles organised at local levels that bring them some money and attention. Even these events mostly run without a sponsor. Often, the artistes pool in their own money, organise a battle and award the winner. “It’s like gambling,” says Chaudhary.

The only other options are teaching and token appearances in Bollywood dance sequences. And we all know how background dancers can go unseen.

“We are treated like jokers on set. Someone will ask you to do a flip and then do a few more and pay you like Rs 2,000 for it,” says Chaudhary. “But what do you do when you just get one shoot a month?” Chaudhary, who won his first international competition in Austria last year, says that most other countries have community centres and campuses where breaking artistes practice and learn from one another.

The Red Bull BC One crew is in India and Chaudhary has been working with the world champions of the past years who will be judging the cyphers in India.

B-boy Lil G from Venezuela, one of the judges and part of the Red Bull BC One’s All-Star Crew, says that Russia and Japan will have the best chance at the Olympics. “India has the potential and also the fire. It just needs to find a good way of making this happen,” he says.

The Delhi Dance Academy, meanwhile, only has sporadic classes in breaking. “Most of the kids are between the ages of 14 and 21 and from families that can’t afford regular classes,” says Md Nazir, head of operations at the academy. “The dance form teaches you to balance your body on your core and then push your limits. It’s no small feat and deserves much more attention.”

So do the women in breaking. Johanna Rodrigues aka b-girl Jo won her first gender neutral battle in Chennai last month. The B-Girls of India, the pan-India community she is a part of, has grown from five to 25 members in the last few years. One of the top national championships, Freeze, has more women finalists every year.

“The Olympic team will need coaches, nutritionists and proper places to practise,” says Rodrigues, who teaches yoga on the side. “It doesn’t come cheap.”

If India is serious about competing in breaking at the 2024 Olympics, its patriotic audience is already late to the party. Watch out for the talent mentioned above and start by supporting those kids in the park. They are preparing to go from neglected streets to centre stage.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)