Up in the skies, Indrani Singh, a senior commander with Air India, found she was quite at peace with what she saw around her. It was on the ground that things seemed less happy.

In the Palam Vihar area in Gurugram, where she lived, she saw a lot of poor children with no hope for the future and access to only dismal education, if they attended school at all. Dozens of children on the streets quite regularly begged, wandered aimlessly, hungry all the time. Somehow what everyone took for granted in many cities across India — and seemed quite immune — to troubled Singh.

In 1995, Singh used her own funds and rounding up a bunch of children, started helping them with their studies and tuition, with a handful of teachers in a rented premise at Gurugram.

She started small, and expected to stay small (as she had a full-time job as a pilot), but soon she found the whole movement had acquired a momentum of its own. What started as a small neighbourhood initiative just kept growing.

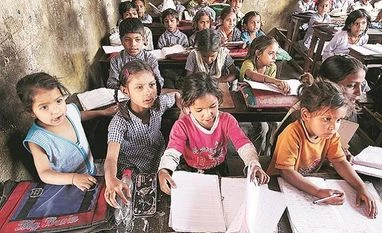

The initiative acquired the name “Literacy India”. To start with, one of its core programmes was Vidyapeeth, a school where students who couldn’t afford better were given as good an education as other private ones. The students appear for board examinations through National Open School.

Vidyapeeth is run out of a building at Bajghera, New Palam Vihar. The beneficiaries come from the lowest economic and social strata. Most are first-generation learners. They are otherwise likely to be engaged in child labour or other menial labour.

Literacy India works on three “E”s — empowerment, education, and employability. Slowly new initiatives have been added and now there are eight programmes that the organisation operates in 11 states. A total of 400,000 lives have been touched in the past 22 years. It now has 200 employees. The organisation has a board chaired by Air Marshal Denzil Keelor.

More recently, it started working closely with PVRs and other cinemas in the city where they often found several homeless children, many of them addicted to drugs.

These children had a very low attention span — 15-20 minutes. Most didn’t go to school. A interactive software was developed to teach these children.

That’s how Gyantantra Digital Dost came about. The self-paced interactive and highly engaging programme uses the main elements of the K5 curriculum and infuses it with problems that these kids typically face: Child abuse, health problems including HIV-positive symptoms, focusing on value education, and teaching them about life skills.

Literacy India pulled in Dell to help it develop the programme.

“We find that technology helps buy back lost time. Within a year we find children able to cover any gaps if they use this digital platform. The choice is between sitting still for hours in a classroom versus working on an interactive tablet,” said Singh. She also said the digital platform was a natural winner.

Literacy India’s biggest push and current energy was focused mostly on this programme, as they saw the highest scope for scaling and a quick spread.

The Gyantantra programme, which has so far reached 100,000 children, is the most scalable and Literacy India is now working to get state governments where it already operates to adopt it.

The programme is largely self-taught and can be run with some guidance from anyone who has passed Class 12. So the attempt is to make state government use it to pull in their street and labourers children as well as offer it in the state government schools to help those students who lag behind to bridge the gap with their peers. Just over 100 schools — where Literacy India — is already directly running some programmes will be adopting the new software. In addition to this, the organization has tied up with nine NGOs who are adapting the digital platform for their own needs.

Singh says that the programme also acts as a refresher by helping students who may have forgotten a certain concept and don’t have access to someone who can sit and clarify it for them. “Children sometimes forget how to take out the LCM or HCF or some concept in fractions”, she explains. The digital platform allows them to revert back and re-learn something they may have forgotten. That works for the teachers as well who often deal with Class 3 and Class 6 level students in the same space and time, an impossible task for most. By using a platform like this, some of the distance between the learning of two children of different ages or even of the same age can be bridged.

The success of the programme with students depends on its right usage. For instance the programme will not achieve the same results if any short cuts or quick fixes are adopted. Any child who has to go through it has to spend a certain amount of time to actually learn. Teachers at times get impatient and try and skip sections to reach the end of the programme but then results suffer, says Singh.

Literacy India is offering the Gyantantra software and platform for free to anyone who wants to adopt it. There is a small basic cost to be covered by the school or NGO for the initial introduction by a trainer of the organisation.

Singh has seen the pull of Gyantantra in her own locality.

A number of homemakers requested access to the software from her and started teaching their own house help and at times their children. Soon, she found some of them cleared their Class V exams and a few wanted to tackle higher levels such as Class VIII. This even helped 25-30-year-olds who have never attended a day of school.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)