Early in November Harish Kapadia was conferred the Piolets d’Or Asia Lifetime Achievement Award from the Union of Asian Alpine Associations, which hands out the “Oscars of climbing”. How did he celebrate? By climbing another mountain, of course. This time, he and his group headed out to explore Incheon in South Korea.

“It was just a day-long trek,” clarifies Kapadia, the only Indian to win the prestigious award. The self-deprecating remark is completely in character for the unassuming 72-year-old. But his achievements are staggering: his major ascents include Devtoli (6,788 m), Bandarpunch West (6,102 m), Parilungbi (6,166 m) and Lungser Kangri (6,666 m), the highest peak of Rupshu in Ladakh. And that is a very partial list.

Kapadia’s tryst with the Himalayas began in 1962 with the Pindari glacier. Over his five decades in the field, Kapadia has mapped unknown areas and opened up climbing opportunities in the Himalayas. “Many people trek or climb mountains. Harish does more, he chronicles stories and histories, gathers information and makes it accessible to others. So his contribution is more than his personal achievements, of which there are many. They have advanced our knowledge and understanding of the high hills and made it easier for others to follow in his footsteps,” says Suman Dubey, former president of the Himalayan Club, who has made many visits to Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, including the Nanda Devi Sanctuary and the Pangi valley, with Kapadia.

For all his Himalayan achievements, Kapadia’s fascination with the mountains began closer to his home in Mumbai — in the Western Ghats. As a school kid, he would go trekking with friends on weekends. As an adult, the Gujarati businessman would plan his expeditions for the off season. “The wholesale cloth business is dull from May till September. So I could go on my expeditions then,” he says. The only glitch in this plan was that the trekking season in Arunachal coincides with Diwali, which meant the northeastern state remained out of bounds till he retired at 55.

He has since remedied the omission, adding it to his yearly calendar, uncovering and documenting new paths. The quest has already helped unravel the mystery of the Tsangpo. “It was not known whether the Tsangpo (as it’s called in Tibet) went further east to Burma or into Assam to become the Brahmaputra. Pandit Nain Singh Rawat was among the people tasked to find answers. But despite the many explorations, no one had actually seen the spot where the Tsangpo enters India,” he says. “A stretch of 100-odd kilometres through densely forested mountains remained undocumented all these years. Moreover, nobody had attempted to try the southern side because of political concerns. In 2003, we mapped the exact point where Tsangpo enters India.”

That is not the only instance of the names of the two explorers cropping up together. Kapadia was only the second Indian to win the Royal Geographical Society’s Patron’s Medal for exploration in 2003 after Rawat. The latter was honoured for being the first to survey Tibet and map Lhasa for the British, disguised as a monk, in the 1860s. Kapadia has been to Tibet thrice — with proper documentation.

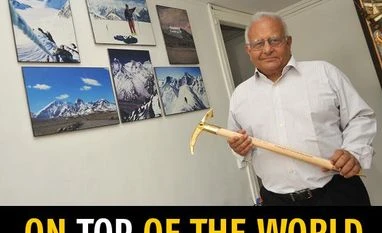

Kapadia after he completes one of his exacting treks.

Given the number of explorations over harsh terrain, Kapadia has seen his share of nature’s wrath. In 1970, while attempting the main peak of Bethartoli Himal, he lost four members in an avalanche. A few years later, in 1974, returning from the successful first ascent of Devtoli peak in the Nanda Devi Sanctuary, he fell into a crevasse and dislocated his hip. It took 13 days for his companions to carry him back to base camp. “It was a case of avascular necrosis, but there was a possibility the bone tissue could be revived after two years on crutches,” says Kapadia. That slender hope was enough for him and, soon, he was back among the mountains he loved.

But Kapadia suffered a profound personal blow when his son, Nawang Kapadia, a lieutenant in the Indian Army, died in 2000 — ironically in his beloved mountains — fighting terrorists in Srinagar. Since then, Kapadia has been vocal about the conflict, and been at the forefront of pushing for a peace park at Siachen Glacier.

Despite his many forays across the Himalayas, Everest has never attracted Kapadia. “Everest is too commercial. People spend crores on expeditions there to make a name for themselves, but the simple fact is that the same money could support 10 other expeditions.” The cynicism fades when it comes to Tenzing Norgay, the first person to summit Everest with Edmund Hillary in 1983. “Norgay was a very simple person. He was my instructor at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute,” he smiles. Other heroes: Jagdish Nanavati, who taught him to read maps and study the mountains; and British explorer Chris Bonington, for the much-needed art of diplomacy. Another friend for life — Pan Singh, a village dweller from Harkot in Kumaon, who has been part of his core group since 1962.

If forging close relationships are among the rewards of a lifelong commitment to the mountains, a deep understanding of the natural world has engendered some sadness about the state of the global environment. “One major impact of climate change is the uncertainty. You never know when the weather will be good, when not. Earlier, you knew June was the best month for pre-monsoon climbs.” Yet, he is not in favour of restrictions. “Blanket ban is no answer. The Nanda Devi Sanctuary has been closed since 1983. On an IMF mission there, we gave a detailed report for it to be reopened. You can place a cap on visitors, appoint liaison officers and take other steps,” says Kapadia.

The explorer has conquered quite a few milestones in ink too. His first book, Trek the Sahyadris, published in 1977, is a classic. Since then, he has penned over 15 books — four on the Himalayas and The Battle of the Roses about Siachen. Kapadia has also served as the editor of the Himalayan Journal, one of the oldest mountaineering journals in the world, for over 30 years. Little wonder then that his library-cum-writing space is chock-full of books. When not reading or writing yet another definitive volume on the mountains, he likes to watch art films.

While he has never wanted to move out of Mumbai, his life seems to have been shaped by the mountains. Both his children were named after sherpas and, yes, he met his wife Geeta on a trek. Showell Styles wrote in On Top of the World, “There is no material gain in climbing a mountain. The thing is useless, like poetry, and dangerous, like love-making. To some people — only a very small percentage of people — mountaineering appears to be as essential and satisfactory as poetry or love-making are to some others.”

That could have been written for Kapadia. The IMF Gold Medal, the Joss Lynam Medal in Ireland, the King Albert I Mountain Award in Switzerland and the Tenzing Norgay National Adventure Award in India all attest to his elemental connection with the mountains. The “golden ice axe” is only the latest honour, and it is yet to find a spot on the white walls that frame pictures of his major expeditions. Perhaps because Kapadia is already busy — planning his next foray into the hills. January will find him in Pachmarhi, Madhya Pradesh.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)