In the monsoon months, as the coconut palm-lined villages of Goa turn cool and lush, residents have to often carefully shepherd visiting snakes and scorpions out of the door. “In the old homes, you are one with the animals,” says Sephi Bergerson, a freelance photographer from Israel. Ever since he relocated to India with family, he has chosen to live in heritage villas, admittedly more for their heightened sense of space and nature than their legacy. The Bergersons spend most of the year in a century-old villa touching the forest in Assagao. With a balcao and foyer, it is “like having three living rooms”. Before that, too, they had rented a bungalow easily more than 100 years old in the neighbouring village of Parra.

There is an undeniable appeal about these ageing houses, although they are oftentimes relics of painful feudal and colonial pasts. The sterility and stiff economies of space that have come to mark a lot of modern architecture are absent in legacy homes. When Varun Sood, founder of an investment firm, drove around Goa and spotted “Siolim House” 23 years ago, there was little interest in acquiring such crumbling buildings. “I bought it at the cost of land.” Sood restored the 17th century structure built in the casa de sobrado style (or the style of Portuguese nobility) over four years. It is now a boutique hotel. He has since acquired another old house there and repurposed it into a culture centre. While Goa is the one place in India with a high concentration of heritage homes, he says times have changed so that there are fewer homes than there are people wanting them.

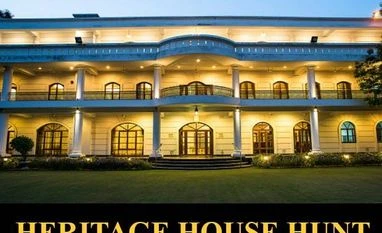

Mettupalayam, near Ooty | Greenwood Bungalow, once owned by a British captain, currently a hotel | Rs 10.5 crore

Indeed, everyone agrees that time-hallowed spaces appear only infrequently on the market. When Vijay Mallya’s assets were sold recently, it was an exceptional occasion as a few bungalows became quickly available in Mumbai, Goa and the Nilgiris. In most cases, buyers are interested in art and value vintage construction and features. As such, auction houses such as Saffronart and Sotheby’s have been aiding in these searches through their real estate units, which otherwise deal with selling luxury apartments. The houses they offer are already painstakingly renovated. Saffronart currently advertises on its website a vivid blue, two-level Portuguese villa located in Goa’s Aldona village that is at least a century old. Its three bedrooms, kitchen and living areas, and latticed verandahs — renewed with antique furniture and upgraded with “modern day amenities” — can be picked up for Rs 8.5 crore. Like most buyers prefer, the 5,000-sq-ft property sits on a large plot of up to 16,000 sq ft, allowing space for a lawn, a wooden cabana, a swimming pool and two staff quarters.

Compared to Ahmedabad, parts of Rajasthan, Punjab and the hills of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, heritage homes are harder to come by in the bigger metros. In restless Mumbai, the few that do go on sale are swiftly snapped up by top industrialists for blockbuster prices. A case in point was Jatia House in Malabar Hill bought by Kumar Mangalam Birla for Rs 425 crore in 2015. The Kolkata market is much the same as owners are reluctant or conflicted in parting with ancestral property, though Sotheby’s has presently found and put on sale a palatial white bungalow on Judge’s Court Road with enhanced interiors and sweeping lawns for Rs 105 crore.

This is not everyone’s cup of tea, however. With heritage homes, there could sometimes be legal tussles at the outset and in almost all cases recurring costs for the upkeep of features such as tiled roofs. The Bergersons, for instance, had their kitchen and washing areas reequipped to modern tastes, and while maintaining the terracotta floor, they painted the rooms in vibrant colours. Sood, meanwhile, decided against using concrete to fortify the walls, knowing that “it would crumble again in 10 years”. Instead, to make his heritage structure more enduring, he thoughtfully selected traditional materials like lime shell plaster. This astounded workers who were accustomed to using mass-produced cement but ultimately won the project a mention in the Unesco Heritage Awards.

Aldona, Goa | A century-old Portuguese villa with striking latticed verandahs | Rs 8.5 crore

For a less committed arrangement, it may be a good idea to rent or hire rooms for some days or weeks. In Mumbai, this is possible to do so at Abode, a heritage art deco building that was leased and restored a few years ago into a boutique hotel by fintech entrepreneur Lizzie Chapman and Abedin Sham, whose family owns the building. Encouraged by the results, the duo similarly restored a 1950s art deco structure in Ahangama in Sri Lanka. Across cities, given a paucity of space, a trend has emerged of old properties being converted into studios and galleries. According to India Sotheby’s International Realty CEO Amit Goyal, many buying heritage structures are looking to build boutique hotels.

Only a decade ago, scores of forts and havelis of Rajasthan went on the market after the government and several private owners decided to sell them. They were being marketed to buyers with an inclination in the hospitality industry. Typically, in the case of large properties, the family would stay in one part and develop the rest as a hotel. Such old homes are not as widely available now. In fact, around 2015, it was reported that authorities in certain districts including in the Shekhawati region had been directed to prohibit the sale of havelis to prevent repairs that would damage their look. It is also not uncommon for ancestral houses in the state to have tens of claimants, making it extremely difficult to get clearances from all.

In the mountainous Nilgiri region along the Western Ghats, where the erstwhile Ootacamund used to serve as a summer capital of the Madras Presidency, there are several colonial cottages and mansions to be found. As it follows these are large holiday homes with wooden details, a fireplace or two, high ceilings and tiled roofs. Around 50 cents, or 21,500 square feet, of land around the bungalow is typically a part of the parcel. Realtors in the district say they have recently seen a resumption in interest, which had stalled after demonetisation. For Rs 8 crore, a century-old two-storey house that originally belonged to a British bridge engineer is on the block, says Fridgo Jacob who runs the firm Real Estate in Ooty.

Where the history of ownership is known, these details are shared, too. The 19th-century Greenwood Bungalow in Ooty, refurbished over three years, was first built by a British officer identified as Captain Scott. It changed hands many times since 1858, until an Indian businessman bought it in 2008 and it is now up for grabs, according to Hari Raamakrishnan of Ooty-based Harshav Real Estate. Buying one of these and making a cultural centre for the local community would be a cool act of counter-colonialism. Also in the hills, albeit this time in the north, is an old home in Nainital that Sotheby’s is selling at an asking price of Rs 7.5 crore.

Near Sim’s Park, Coonoor | British-era cottage ‘Bliss’, aged over 100 years and measuring 3500 sq ft | Rs 12 crore

A thorough check of all the paperwork and title clearances done by the seller is standard practice at Saffronart, says Shaheen Virani, associate vice-president of client relations, and once the auction house finds an interested buyer, it is a pre-requisite for them to have the papers vetted by their lawyers too. Famously, Cyrus Poonawalla’s purchase of Lincoln House in Mumbai for Rs 750 crore became embattled after the external affairs ministry in India challenged the American Embassy’s right to sell it. Anuj Puri of Mumbai-headquartered Anarock Property Consultants offers an extended checklist for prospective buyers, including taking up a cost and structure audit before embarking on any restoration. It is also advisable to pick an expert restoration team in advance. Further, he says a buyer must be prepared for inflated air conditioning bills for the disproportionately large rooms in old-style structures. Also, approvals may have to be sought from civic authorities before revamping any part of a historical building.

A number of heritage homes is also advertised on more mainstream property-selling platforms. One such post from Kolkata claims to be offering a building of 100 years, whose wooden windows have disintegrated and paint chipped, in the Shobha Bazar area for Rs 95 lakh. Over in Kerala, for sale in Kollam for Rs 88 lakh is a 75-year-old one-storey modified tharavadu house, the traditional homes of Nair joint families. It features the signature deep sloping tiled top and thick wooden pillars. It is a short distance from the Thalassery lighthouse and adventure sports hubs. Beena V, who created the post about her ancestral home, believes it will be suitable for someone who wants to run a guesthouse. Northwards in Kottayam, a renovated heritage house with wall-to-wall woodwork is advertised to be on sale. However, these sites do not bear information on titles and other clearances and the authenticity of the posts could not be independently verified.

Unlike high rises, which tend to turn even immediate surroundings into faraway spectacles, heritage homes come with a sense of communion. Standing in various states of repair, often in picturesque regions and sometimes in the midst of metros full of posh new superstructures, these surviving examples of traditional architecture seem like brave anomalies. A certain braveness is discernible also in the people who gamble to keep them alive.

)