On March 27, as Parliament passed the new Mental Healthcare Bill that decriminalised attempt to suicide by the mentally ill and sought better healthcare for people suffering from mental illness, Health Minister J P Nadda thanked Congress MP Shashi Tharoor on Twitter for his “valuable” suggestions made during a discussion on it in the Lok Sabha.

In an impassioned speech three days earlier, Tharoor had said he had “lived with a victim of mental illness” and that there was nothing sadder than witnessing “a loved one with mental illness at close quarters”. He had backed his emotional pitch with sound data and a thorough understanding of the subject.

A memorable speech is how many later described it. A lot of effort had clearly gone into putting it together. Tharoor says he didn’t do it alone. “I had two very bright young people, one of them a LAMP (Legislative Assistant to Member of Parliament) fellow, working on it. They contacted professionals, looked up previous laws and came up with a number of points that went into the first draft of my speech,” says the MP from Thiruvananthapuram. Later, Tharoor met some sufferers as well as experts in his constituency and sent more points to this team in Delhi which then updated the draft. “I finally put my own gloss on it but the substance came 90 per cent from their work,” says Tharoor.

Barely a kilometre from Parliament House, where Tharoor made his powerful speech, is the two-room office of Rajya Sabha MP Rajeev Chandrasekhar. Here, a team of three researchers works through the day. Another six members of the MP’s personal team, who add punch to his parliamentary speeches and on-ground work on issues as diverse as “one rank, one pension”, right to privacy, net neutrality and child sexual abuse, operate out of Bengaluru. It’s a substantive setup and he funds it out of his pocket.

Like Tharoor and Chandrasekhar, Biju Janata Dal (BJD) MP Jay Panda funds a private policy team of four that works out of a small office near his home on Mahadev Road in New Delhi.

Across party lines, a growing number of vocal lawmakers are engaging the services of professional researchers and public policy assistants to help them do their job better. Among them are Supriya Sule (Nationalist Congress Party), Rajiv Pratap Rudy (Bharatiya Janata Party), Tathagata Satpathy (BJD), Derek O’Brien (Trinamool Congress) and Manish Tewari (Congress).

The researchers, who are mostly in their 20s, include students who have completed their undergraduate courses, lawyers, engineers, IT professionals and architects. “Most of them are here simply because they want to get an experience of public policy. And what better way to do that than to work with an MP?” says M R Madhavan, president and co-founder of PRS Legislative Research, a public policy research institution.

PRS runs the LAMP fellowship under which young Indians below 25 are assigned with an MP from the beginning of the Monsoon session to the end of the Budget session of Parliament. During this period, they provide extensive research support for the MPs’ parliamentary work: from helping write their speeches and working on their Zero Hour statements to drafting Private Member’s Bills for them. The researchers earn Rs 20,000 a month during the fellowship, paid by PRS.

“They are of immense help, especially when it comes to research,” says Sule who has been working with LAMP fellows for the last five years or so. “Suppose today I am speaking on HIV in Parliament and tomorrow I have to speak on the Motor Vehicles (Amendment) Bill. By the time I return from Parliament, the researchers, all of whom are immensely hard working, have already pulled out information on the next day’s topic and marked out the important points. I can then prepare myself faster and better.”

Sule arranges a three-day packaged trip to Baramati for the research fellows so that they gain first-hand experience of her constituency.

The LAMP fellowship is but one source of the talent pool that the MPs dip into for abject want of any formal, structured research support from Parliament. For, unlike in the US, where the senators and representatives have staff to help them with research, handle their appointments and so on, MPs in India get a mere Rs 30,000 to engage one person.

“For that kind of a salary, if I look for a more experienced person, someone in the 40s, I would not get such professional quality,” says Tharoor. A person in the 20s is, however, willing to sacrifice a high-paying job to work with an MP for a few years because of the immense experience she would gain.

“About 40 per cent of them eventually do end up in the political or policy space,” says Madhavan. Many others go on to study in some of the world’s finest universities. Some, like Reeti Roy, 28, who assisted Tharoor as a 23-year-old, have started their own enterprises after doing projects with Harvard and Unicef.

Tharoor says he always like to have a young lawyer in his team “because I like using the Private Member’s Bill as a vehicle to advance my political thinking. Having a lawyer who can prepare the legislation, work with NGOs and then decide what is to be done is very helpful.”

Sometimes MPs find youngsters who are interested in public policy approaching them directly. “If I am impressed by the tone or content of their email, I ask to meet them and then maybe get them on board,” says Tharoor. And when it’s time for them to leave, he asks them to recruit their successor — by that time they know the kind of work involved.

His last assistant came to him after a stint at McKinsey, worked with him in three different roles and later went off to do a master’s course in public policy from Columbia University.

‘By the time I return from Parliament, the researchers have already pulled out information on the next day’s topic and marked out the important points’

Supriya Sule

Lok Sabha MP from Baramati

Of the team of three he now has, one is a man in his early 20s, a special assistant who has family links with the erstwhile Nizam of Hyderabad. This young man sees a long-term political career for himself in Hyderabad and has committed himself to Tharoor for two years to learn the ins and outs of Parliament, from the bottom up — networking with both the Parliament staff and the MPs. “He has also worked on my interventions on Rule 377 (of Lok Sabha, which allows members to bring to the notice of the House any matter which is not a point of order).”

For Chandrasekhar, a first-generation politician, the policy team is critical. “I got into politics in 2006 as a non-politician and knew I had to approach Parliament with research, facts, data and solutions if I had to create a space for myself,” he says.

His team, which includes a former photo journalist and a website researcher, grew as his areas of interest expanded. “If I know and say things reasonably confidently and with credibility in Parliament, it is because of my research team that helps me dig deep into these issues and frame my views,” he says. “When I came into politics, I did not know about a lot of issues apart from telecom and technology.”

The constant updates and ground reports he gets from the team and which are based heavily on facts and statistics, he says, have helped him stay ahead of the curve. Chandrasekhar fights a lot of his battles through public interest litigations, which are drafted by his team with lawyers. Among the big ones was the suit to seek voting rights for armed forces personnel, with the Election Commission deciding to permit them to vote at their place of posting.

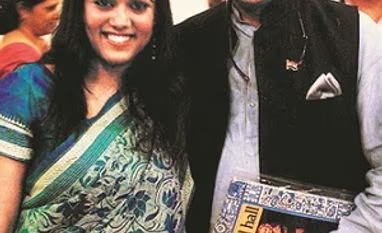

Shashi Tharoor (right), Congress MP from Thiruvananthapuram, with his LAMP fellow, Reeti Roy, in 2013

The impact of an informed analysis that is supported by policy teams can affect legislative outcomes as well. Iravati Damle, 28, who worked with Panda, recalls the time when the amendment to the Right to Information Act was being tabled in Parliament: it excluded political parties from the RTI ambit and created huge furore on social media. Some of the MPs who had policy teams were able to sense the angst of the people against the amendment and tapped into it. “We ran a massive public opinion campaign with the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative that was at the forefront of fighting this amendment to ensure transparency in political parties,” she says.

This involved making calls to every MP and asking whether she would vote in favour of or against the amendment. It put a lot of MPs in a tough spot, and the proceedings in Parliament on the day it was supposed to be passed were extremely dramatic. “The pressure that was built by the policy teams of these three or four MPs led to the government taking notice. The amendment was withdrawn and the Bill was referred to the standing committee at the very last minute when it was actually attempted to be passed in Parliament.”

Vishesh Jhol, 27, who initially worked with Congress’s Tewari as a LAMP fellow and later joined him as assistant private secretary in the information and broadcasting ministry, recalls the time in 2013 when the Planning Commission released the poverty statistics. Tewari, who would routinely wake up at 5.30 am, called him at 6 that morning and asked him to analyse the data to see if the United Progressive Alliance government could bring the positives out of it. As Jhol structured the data, he found that in the last 10 years of the UPA government, poverty was at the lowest in the history of independent India. Tewari went to the press conference with that happy report.

Sometimes, though not often, MPs also turn to research and policy assistants for feedback and advice on how to spend their local area development fund, or MPLAD fund, which works out to the tune of Rs 5 crore per year.

Besides helping to improve their performance in Parliament, these young policy assistants sometimes also act as the MPs’ “memory devices”, as Meghnad S puts it. Meghnad, who used to describe himself as the “resident policy nerd” before he adopted the prosaic designation of chief-of-staff, has been working with BJD chief whip Tathagata Satpathy since 2014. His job is to scan each and every piece of legislation that comes up and find loopholes in it.

He also makes it a point to remind the MP of matters close to the heart but momentarily forgotten. Satpathy, for example, had often spoken about the logic of “one country, one number” policy. “Why should you have to get a new car registration number if you change your state, he would argue,” says Meghnad. Earlier this month, when Satpathy was preparing for a speech on the Motor Vehicles (Amendment) Bill, 2016, Meghnad reminded him of this point, which the MP then included in his speech.

Not every MP has the money to afford such a team. And so they struggle with lack of data and information. “As a result, Parliament suffers,” says Chandrasekhar.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)