On June 2, inside the commentary box at Edgbaston, Sourav Ganguly and Virender Sehwag were enjoying a chuckle while calling the Champions Trophy game between Australia and New Zealand. A ball earlier, the flashing blade of Martin Guptill had sent a wide delivery from Josh Hazlewood cracking over point for four. Sehwag, ostensibly in awe of a shot he had so majestically mastered himself, let out his dearest Hindi superlative, “khoobsurat” (beautiful). Ganguly agreed with his former protégé.

Earlier that day, Ganguly had apparently met the Indian team at its hotel in Birmingham in a desperate attempt to defuse tensions between skipper Virat Kohli and coach Anil Kumble. And the whimsical Sehwag, with a firm eye on Kumble’s job, had just sent out his two-line curriculum vitae to the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI).

If Kohli has his way, Ganguly and Sehwag will be sitting across each other in a few weeks’ time. Along with Sachin Tendulkar and VVS Laxman, the former Indian captain is a part of the BCCI’s three-member advisory committee that will decide who next lands the most distinguished coaching position in world cricket.

This dual position held by Ganguly was one of the many things flagged by Ramachandra Guha in a fierce letter post his resignation from the Committee of Administrators (CoA) last week. In January, the Supreme Court had put the CoA in charge of Indian cricket to fully implement the recommendations of the Justice R M Lodha Committee. In addition to Guha, the court had nominated former Comptroller and Auditor General of India Vinod Rai, IDFC Managing Director & CEO Vikram Limaye, and former women’s Test cricketer Diana Edulji as the other members of the committee.

Ganguly, in fact, performs a quadruple role: he also acts as president of the Cricket Association of Bengal, and is a part of the Indian Premier League’s (IPL) governing council as well. Laxman, too, works as a broadcaster almost all year long.

Appointing an enforcement cohort akin to the CoA was never the Supreme Court’s intention. It was forced to step in after all attempts to get the BCCI to clean up its house by following the Lodha reforms failed — a reprehensible episode that culminated with the dismissal of Board President Anurag Thakur and Secretary Ajay Shirke.

More From This Section

With exalted names at its helm, the CoA was seen as a body with unmatched probity that would successfully free Indian cricket of abhorrent machinations and provide a much-needed, scandal-free finality. With Guha’s letter — where he questions the inaction of his fellow members — all that hope lies in tatters.

Apart from casting doubt on his colleagues’ unwillingness to implement the reforms, Guha highlights several other worries: conflict of interest involving players and coaches, the awarding of player contracts, former administrators flagrantly disobeying the Lodha rules by attending official meetings, and the ubiquitous “superstar culture” that bedevils Indian cricket.

When contacted, Guha stated that “he has said whatever he wanted to in his letter” and refused to comment any further.

By underscoring player behaviour and the payment structure for domestic players, many feel that Guha has perhaps veered into territory he necessarily needn’t have — refashioning the BCCI’s functioning should’ve been the CoA’s priority.

Among the myriad changes proposed by the Lodha Committee, only the one that prevents any BCCI office-bearer from being over 70 years of age has been successfully imposed. For the rest, the progress is not clear as the BCCI is yet to fall under the ambit of RTI. The one-state-one-vote policy has been zealously opposed by several state associations, there are still no separate governing bodies for the IPL and the BCCI, and little headway has been into making cricket betting legal.

After Guha’s resignation, many have questioned Vinod Rai’s (left) ability to lead a cricket body despite his stellar record (2G and Coalgate)

The role that the CoA was originally intended to perform — governance or management, or both — isn’t entirely clear, though Lodha himself warned the CoA against mixing the two as late as last month, saying that both are vastly different areas and it should only focus on the former.

“The CoA was meant to be a transitional body that was to help Indian cricket back on its feet. However, it’s true ‘role’ is pretty much an enigma,” says sports attorney Desh Gaurav Sekhri.

Back in January, the court had appointed Amitabh Chaudhary and Anirudh Chaudhary as administrators, but only for the purpose of representing India at International Cricket Council (ICC) meetings, which essentially means that a bulk of the BCCI’s functional load is solely handled by Rahul Johri, the CEO.

There is, however, downright agreement on the level of ineptness at the CoA that forced Guha to quit. Kirti Azad, former cricketer and Rajya Sabha MP, blames Rai for most of this strange passivity shown by the body. “I’m not quite sure if he was ever fit for this role. He operates like a bureaucrat and just cannot work in the BCCI. You need brave, powerful figures to revamp the sport,” he says. “The CoA was always a toothless tiger.”

Incidentally, the Banks Board Bureau, another advisory body headed by Rai, finds itself in a similar limbo. After being constituted amid much expectation last year, it has made minuscule contribution to the sector.

For the record, while Rai is a favourite of the Bharatiya Janata Party brass for having exposed the 2G and Coalgate scams during UPA II, Azad is a vocal rebel who feels he has been sidelined. Some bit of Azad’s hostility needs to be seen in that light.

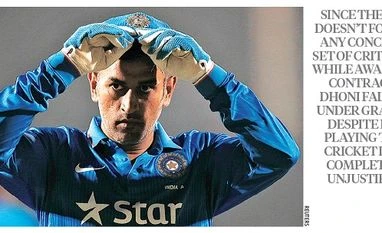

In December 2014, Mahendra Singh Dhoni retired his white flannels, finishing as India’s most successful Test match captain. Having being somewhat relieved of the decision-making eminence he once enjoyed in the Indian dressing room, Dhoni’s visage now often reflects the blitheness that typified his early international career. The bumper nature of his contract, however, has remained unaltered — something Guha says he objected to. Dhoni enjoys a Grade A central contract, which fetches him, in addition to match fees, Rs 2 crore every year.

“I agree with Guha. Grade A contracts should only be given to players who play Test matches. That has always been the case,” stresses Azad. While Azad espousing the cause of Test players has obvious merit, BCCI’s contract rules aren’t chalked out that way. The Board, for a number of years, hasn’t followed any concrete set of criterion while awarding contracts. For the younger players, recent performance is considered; for the experienced ones, stature mostly does the trick.

“Dhoni is still performing for India. His importance is immeasurable. That he doesn’t play Test cricket shouldn’t be a problem,” says a former Indian opener. Others rebut Guha by pointing to Cheteshwar Pujara and Murali Vijay, who, like Dhoni, don’t play all formats and still fall under a Grade A contract.

Ramachandra Guha’s resignation from the Supreme Court-appointed Committee of Administrators has shown that Indian cricket’s road to reform is a long and arduous one

The conflict of interest argument presented by Guha is far more consequential. For instance, the case of Rahul Dravid, who is the India under-19 and India ‘A’ coach and also doubles up as mentor for the Delhi Daredevils, is described by many as an “open and shut” one. “Can you imagine Anil Kumble managing an IPL team? National coaching posts are full-time jobs. This is morally wrong,” says a former Indian coach who has managed in the IPL.

Conversely, with the under-19 and ‘A’ sides only playing for 10 months a year, Dravid has every right to work in the IPL. And his missing a camp at the National Cricket Academy is hardly as significant as it seems, since two coaches — Narendra Hirwani and W V Raman — already work full time with the players there. Moreover, according to the Lodha recommendations, Dravid cannot be held complicit. “It is important to understand that ‘conflict of interest’ isn’t a legal term, but rather a best practice to be followed,” says Sekhri.

As for Sunil Gavaskar, who is a director at Professional Management Group — the firm that manages Shikhar Dhawan and Rishabh Pant — and does TV commentary, the batting great has said that he has never tried to influence the selection committee. Mark Waugh, for example, is an Australian national selector who also does commentary during the Big Bash — an unimaginable proposition in India given that the BCCI produces its own TV feed.

The antagonism with Guha, though, runs deep. Some Board sources say that some of the CoA’s policies have been against the interests of Indian cricket — the tipping point of which came at an ICC meeting in Dubai in late April, when the BCCI was humiliatingly outnumbered trying to preserve the “Big Three” revenue model. The CoA was accused of inadequately defending the rights of the BCCI. Following that embarrassment, the BCCI was mulling a pullout from the Champions Trophy, a move the CoA advised it against. “The self-righteousness is nauseating. Many feel that they haven’t stood up for Indian cricket,” says a source.

Another point of dissonance is the salary paid to domestic players: a “paltry” Rs 30,000 for a day of Ranji Trophy cricket. Guha wants that figure augmented; the Board has never been too keen. Ironically, the CoA rejected a plea by Indian players for a pay increase, saying it wouldn’t increase the 26 per cent share from the BCCI revenue that is allotted for players. Interestingly, the BCCI excludes 70 per cent media revenue and the IPL revenue from the base pool, resulting in a much smaller amount at the players’ disposal.

“The issue of domestic players being not paid enough is a pertinent one. We need serious improvement there; we cannot be neglecting that anymore,” says a former Indian spinner. “As far as the Indian players go, they are paid quite handsomely. Plus, they also have endorsements.” And experts conclude that the superstar culture Guha alluded to will continue to thrive.

Most worryingly — and tellingly — no remedies are in sight for the multifarious complication that Indian cricket has metamorphosed into. Bedi calls for a more professional approach with people having relevant experience leading the charge. Azad says that sports administrative expertise is vital. “Rai may have cracked the 2G scam but that doesn’t mean he can run Indian cricket. Moreover, you don’t want people with any kind of political affiliations,” he says.

Sekhri adds that the Supreme Court — when it hears the matter on July 14 — must decide on the tenure of the CoA. “This was supposed to be a temporary body. We need a proper timeline, so that fresh elections can be called. We also perhaps need a former male cricketer on the committee,” he says.

In the past two years, numerous changes in management and attempts at reform have failed to resurrect the inglorious image of cricket administration in India. Indian cricket, it seems, pays overwhelming obeisance to a vapid, old adage: the more it changes, the more it remains the same.

)