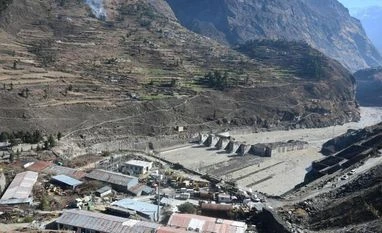

That’s one part of the story of the Rishiganga hydroelectric project. In another, beyond the curse of the nature, there is a mix of strange events that make this 13.2-Mw project, located at Raini village in Uttarakhand’s Chamoli district, look like it was never meant to be.

The work on the project commenced in 1996, with a Kolkata-based realtor bagging the contract. Not much work done for a decade, the project was later taken over by two Ludhiana-based business families. That was when things seemed to have started going awry. The two families – the Mehras and the Nagraths – were partners in various businesses – from milk to paints, chemicals, and many others. The Mehras were mostly majority shareholders and the Nagraths minority shareholders in many of these companies, including the Rishiganga project.

A trouble over business dealings appeared to have erupted sometime in 2012, a year after Rakesh Mehra, the patriarch of the family reportedly died in a freak boulder strike at the site of the Rishiganga project. The Nagraths claimed in court that they were victims of “oppression and mismanagement” by the Mehras and alleged that they were fraudulently ousted from the board of all companies, including the flagship Rajit Paints. This, the Nagarths claimed, was executed by the Mehras by forging their share transfers and resignation letters from the board of directors – a coup of sorts. Besides police complaints, petitions were filed against the Mehras and their companies in New Delhi’s company law tribunal.

The feud between the two co-promoters was apparent in a case involving a company called Rampur Hydro, which had been chosen in 2008 to be the independent power producer (IPP) for developing a 5-Mw plant in Himachal Pradesh’s Shimla district. The Nagraths’ petition in the Delhi tribunal led to an injunction, in which Rampur Hydro was prohibited from raising loans from banks by mortgaging assets. The company had won the contract for a 5-Mw power project in Shimla in 2008 for which work had still not started. The Mehras had sold off their shareholding to a Delhi-based company, which now wanted the restrictions on raising loans lifted. This, they claimed, was preventing them from raising Rs 42 crore needed to build the dam with their licences on the verge of cancellation. Additionally, Rampur Hydro had paid almost Rs 3 crore in employee salaries and extension fees to the Himachal Pradesh government for its delay in implementing the project from 2008 to 2014. Rampur Hydro’s Rs 45 crore contention would eerily resonate in Rishiganga a few years down the line.

The Nagraths, meanwhile, continued with their claims that they had been fraudulently divested of their shares from Rampur Hydro and were victims of fraud and forgery. On January 24, 2014, the tribunal lifted the restrictions on raising loans – effectively repudiating the Nagraths’ claims that they had been unfairly ousted by the Mehras from their business partnerships.

Documents from the Registrar of Companies (RoC) show that the two families continued to be co-promoters in the Rishiganga project – at least on paper. But barely four years after the dam became operational in 2012, it was swept away for the first time in the 2016 Uttarakhand flash floods. From a revenue of almost Rs 6 crore in 2016, its cash flow dried up after the disaster. With the dam wrecked and its liabilities beyond its assets, the Rishiganga project was put on the chopping block. Documents show that Rishiganga Power Corporation owed its creditors Rs 164 crore. Much of the money was owed to Punjab National Bank, which took a haircut of Rs 70 crore in the resolution deal. With the Mehras and Nagraths unable to salvage the project and repay their dues, the company was put through the insolvency resolution process.

An email sent to Rohit Nagrath, who runs a paint business in Ludhiana, remained answered as of the time of publishing of this report. The Mehras could not be contacted. A former employee of their milk business said that the business had shut shop. The Ministry of Corporate Affairs had disqualified the two members of the family from acting as directors in any company under a clean-up drive in 2018 for a period of five years. Their responses will be published when received.

In 2018, Delhi-based Kundan group paid Rs 45 crore to banks to buy Rishiganga Power Corporation. The group, which claims to run the largest gold refinery in India, is a major importer of the precious metal and is into jewellery, bullion minting, petro-chemicals, agro-forestry and hydro power. A specific set of questions sent to the company and its director had not been answered as of the time of publication.

The Kundan group put a plan in place to rebuild the Rishiganga project. While it used its own money to buy Rishiganga Power Corporation, it approached the Punjab National Bank for a loan of Rs 50 crore to rebuild the dam. By 2019, the bank had disbursed Rs 30 crore to the group. It had earmarked Rs 18 crore to be spent on the project in 2019. The same year, one Kundan Singh (unconnected to the business group), a local resident of Chamoli, filed a public interest litigation (PIL) alleging that the company was blasting through mountains to rebuild the dam. This in effect was a threat to the sensitive Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve in the vicinity. He further alleged that construction debris was being dumped into the river, obstructing its flow and thereby posing a threat to life downstream. Local reports also suggest that a lot of activity was visible at the dam site.

But then, on February 7, history and tragedy repeated themselves at the dam site on the Rishiganga river. It has been 25 years since the dam started trying to generate electricity. It has done so for barely four years. The river, quite like the people who have owned the dam over the years, seems to be in no mood to relent.

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)