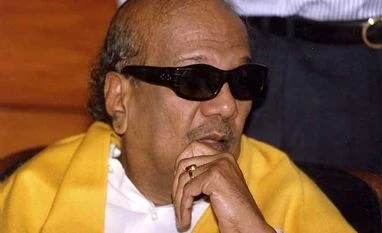

If there was anyone who excelled in the art of the possible, it was Muthuvel Karunanidhi, (Mu Ka in Tamil), the patriarch of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). Days before he passed away on Tuesday (August 7, 2018), the DMK on July 27 observed the 50th anniversary of his presidentship of the party.

Few politicians can claim to leave behind such a brilliant political legacy. This is even more impressive if you consider his origins. Born in 1924 in Tamil Nadu’s Thanjavur district to parents who belonged to the Isai Vellalar community, Karunanidhi saw the inequity of Tamil society, as well as the instruments with which these could be rejected. His family’s circumstances were such that he could not study beyond class 5. But he gradually acquired mastery over the language and became a Tamil scriptwriter. He was among millions of youth who came under the charismatic political spell cast by E V Ramaswamy Naicker or Periyar, and put together the youth wing of the Dravida Kazhagam (DK, as EVR’s party was called), referring to it as the Tamil Nadu Tamil Manavar Mandram.

When one of Periyar’s followers, C N Annadurai broke away from Periyar, it was Annadurai that Karunanidhi followed, becoming a founder member of his party, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), and taking the position of the party treasurer. Annadurai did not hide his fondness for his talented lieutenant and treated him on a par with M G Ramachandran, who used his reach as a silver screen heartthrob to become puratchi Thalaivar (revolutionary hero). There are those that argue that even there, it was Karunanidhi and his catchy turn of phrase that made MGR what he was. But it was much more than that. The dialogues of films like Parasakthi crafted the anti-upper caste ideology of the DMK in a way seen nowhere else in India. This extended to the anti-Hindi stance of the party: At 13, Mu Ka cut his hand and in blood wrote Tamil Vaazhga (Long Live Tamil) on the walls.

When Annadurai got a chance to form a government for the first time, Karunanidhi became minister for public works and transport. It was under his watch that the first steps were taken to nationalise bus transport in Tamil Nadu, a state where the public bus service continues to be best run among all of India’s states. When Annadurai died without naming a successor, Karunanidhi elbowed aside the other top leader and ideologue V R Nedunchezian and became chief minister at 45 in 1969.

As long as Annadurai was alive, the MGR-Karunanidhi rivalry was in control. But as beautifully described in Mani Ratnam’s film Iruvar, the friendship turned into jealous rivalry fanned by entrenched vested interests. In 1972, following MGR’s public charge that Karunanidhi had embezzled party funds, MGR was expelled from the DMK. He formed the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), creating one more pole of opposition to the DMK, in addition to the Congress, which was already there.

For the decades that followed, Tamil Nadu’s politics was about rivalry between the DMK and AIADMK. But for all that, many schemes started by the DMK were continued and refined by the AIADMK government. The programme for slum clearance and state-sponsored housing, rice at re 1 a kg, the coverage of Tamil Nadu’s below poverty line population by the public distribution system (PDS) that provided subsidised rice, sugar, kerosene and wheat to card holders and saris and dhotis during festivals. All these were benchmarks laid by the DMK that the AIADMK could only emulate and improve. Between 1970 and 1976, the years when Karunanidhi was in power, the state gross domestic product grew 17 per cent, and per capita income 30 per cent, and infant mortality rates dropped from 125 in 1971 to around 103 by 1977.

The downside was an inevitable dilution. Karunanidhi strongly opposed the Emergency of 1975 and his government was dismissed in 1976. An enquiry into corruption led to public disclosure of financial impropriety. DMK stayed out of power for 13 years after that. In 1989, after MGR’s death, the DMK came to power in the state but lost badly in the Lok Sabha elections. Despite that, his nephew, Murasoli Maran became a minister in the V P Singh-led central government.

On the home front, things were not as smooth. A man after his own image and a loyal leader, V Gopalaswamy (Vaiko), was emerging as a pole in the party. But Karunanidhi saw more promise in his son, Stalin. Vaiko left the party, but never hid his admiration for Karunanidhi. Stalin’s growth irritated other groups in the family – most of all, the Madurai-based Azhagiri, Karunanidhi’s elder son. At a public meeting, Karunanidhi gave vent to his anguish by referring to the family dispute in these terms: “A clock has two hands, but only when they work together can we tell the correct time.” Azhagiri had his own ellipsis… “when we cry, tears flow out of both eyes”, he said. In any event, Azhagiri was cast aside and Stalin became Karunanidhi’s heir apparent, making space for his half-sister, Kanimozhi, many say Karunanidhi’s favourite child.

The Manmohan Singh years (2004-09 and 2010-14) represented the best and worst of times for the DMK. The party was in power at the Centre throughout, but in Tamil Nadu its fortunes were eclipsed by two successive victories by the J Jayalalithaa-led AIADMK – in 2011 and 2016. But the DMK’s succession plan was put in place by Karunanidhi a long time ago – so the succession has been orderly.

For the Dravidian patriarch, the current events are like a re-looping movie: Two top film stars, Kamal Haasan and Rajinikanth have jumped into politics. Can the DMK meet the challenge? Karunanidhi will not be there to see it. But he should be content at a life lived to the full.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)