India’s rivers are central to the life of its people and the Hooghly River, a 160-mile branch of the Ganges that runs through the city of Kolkata in West Bengal, is no different. In the late afternoon, I walked to Babu Ghat, and onto the broad concrete slipway that descended into the water, where a few moored boats bobbed slowly and men and children bathed in underclothes.

The sticky heat had finally begun to break and people were out sitting on the banks of the Hooghly, chatting, eating, or just watching the sun glitter on the water as it began its descent. A young man approached me and, apropos of nothing, asked if I liked Kolkata. When I replied yes, he nodded and said, “Kolkata is the heart of India.”

After four days in Kolkata (or the Anglicized “Calcutta”), the capital of West Bengal and known by the nickname, City of Joy, it was difficult to argue. Kolkata, a city strongly associated with British rule and the East India Company, has a fascinating relationship with its colonial history. With a rich literary tradition and strong educational institutions, Kolkata also has a more relaxed and peaceful feel than some of India’s other modern metropolises. Combined with spicy Bengali cuisine and a love of fried street food, it proved a rewarding place to explore — and naturally, I managed to keep my budget in check.

My comfortable room ($27 per night) in the Ballygunge area of the city was centrally located and ideal for exploring the rest of the city. I rented the room through Airbnb, which I use judiciously. When traveling solo, I’ll typically rent a room in a family’s home: In many instances, hosts have happily clued me in on things to see and do. One tip: Click on the host’s profile picture to see how many properties they have listed. If I see that a host is managing a large number of places, I may choose to stay elsewhere — I’m more interested in using Airbnb as a cultural exchange than as a hotel.

My hosts, Saroj and her daughter, Mrinalini, knew their city well and were happy to offer insight. They both loved the intellectual curiosity and open-mindedness of the city. “Calcutta is laid back, old world, colonial. People have time; it’s a little easier,” said Mrinalini. “In Bengali culture, women are generally considered equal,” she added, compared to places like Delhi. “In some cases they’re actually considered superior: It’s very progressive. I didn’t even think about being feminist because I never needed to be.”

A history of British Colonial rule

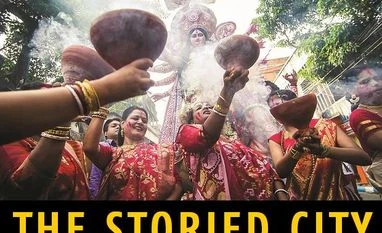

File photo: Married women perform the dhunuchi naach, a stylised dance during the send-off for the goddess at the end of Durga Puja. (Photo: Dhrubajyoti Bhattacharjee)

Kolkata’s colonial history is on display at the Victoria Memorial, a grand museum with attractive surrounding gardens that began construction in 1906 and opened to the public 15 years later (Tickets are 500 rupees, a little less than $7, for foreign visitors, and 30 rupees for locals). I made the 30-minute walk from my room in Ballygunge, dodging taxis and weaving between vendors selling fresh fruit and chaiwalas pouring searing hot tea into thin, earthen cups. (On the way there, I made a quick stop to appreciate the soaring Gothic Revival beauty of St. Paul’s Cathedral, an Anglican house of worship completed in 1847.)

Within the Victoria Memorial’s magnificent marble walls are some interesting artifacts and exhibitions. “The Artist’s Eye: India 1770-1835” has a number of handsome paintings from the likes of Thomas Daniell and Tilly Kettle, who arrived in India in the 1760s and was one of the first prominent English painters to work in the country. On the other side of the exhibition hall, a more intriguing exhibit catalogs the timeline of British colonial rule in India through photos, prints and historical relics.

Kolkata was made the capital of British India in 1772, but growing nationalist sentiment and resistance to British rule led to Britain moving the capital to Delhi in 1911. A devastating famine during World War II killed millions in Bengal — some lay blame for the tragedy directly at the feet of the British. A caption under one of the last photos in the exhibition reads: “Calcutta benefited from British rule more than other Indian cities, and also paid a greater price.”

I was mulling over those words when I struck up a conversation on the street with Aradhana Kumar Swami, a teacher who was picking up his wife and buying supplies in Kolkata before embarking on a 40-hour train journey home to the Kerala region. “No, not at all,” he responded, when I asked if there was any lingering resentment toward the British. “We have no problem with the British.” Some people, he said, had an issue with the opulent Victoria Monument, however. Queen Victoria, he said, never once visited the city. “That could have been a school or something,” he said, and shook his head.

It’s easy to see where Kolkata’s reputation as an educated city comes from: simply visit the College Street Book Market, near the University of Calcutta. I took the underground Metro to the Central station (5 rupees) and cut over to College Street. I immediately heard chanting, and came face-to-face with a large group of student protesters, waving signs and yelling slogans. I asked a couple of people what the protest was about — they said it was government-related but wouldn’t be more specific.

Books, from markets and shops and roadside stalls

The energy from the protest carried over to the book market, probably the largest collection of books I’ve ever seen in one place. Piles of books of all kinds — from engineering to Shakespeare to Dan Brown — spilled over from roadside stalls onto the street. I saw one barefoot vendor precariously negotiating his wares as if he were a mountain climber, looking for a particularly hard-to-find volume.

I wanted something by the Nobel Prize winner and Kolkata native Rabindranath Tagore, and after asking around, I found a book of his short stories at a shop called Bani Library for just 95 rupees. I took my book around the corner to the College Street Coffee House, a favourite hangout for students, writers and intellectuals for the past 75 years. The place has an immediate shabby charm — waiters dressed in green uniforms with gold belts navigate the cavernous, dimly lit room full of tables packed with people having animated discussions. I shared a table with a young couple and enjoyed a coffee with a plate of chicken chow mein noodles (100 rupees).

There is a strong spiritual side to the city, as well. I hopped into an Uber and rode up the Dakshineswar Kali Temple, north of the Nivedita Bridge (the ride from the city center was about 250 rupees). The beautiful riverside structure has temples to Shiva and Vishnu, and the surrounding area has a festive, carnival-like atmosphere. Vendors hawk strings of bright yellow and orange marigolds; others call out, telling you that they’ll watch your shoes while you go into the temple. Nearby, people selling snacks and drinks shoo away monkeys trying to steal a quick bite.

Security is tight at the temple — no photos are allowed, and you’ll have to check your cellphone, too (3 rupees), as well as your shoes (2 rupees). I joined a long queue of worshipers carrying gifts of money and flowers and got a peek at the Sri Sri Jagadiswari Kalimata Thakurani idol, bright red tongue visible and a foot placed onto a man’s chest. I asked a stranger if he could tell me more about the significance of the idol, and he simply replied, “Mother!”

The Mother House of the Missionaries of Charity, or just the Mother House, is another essential place to visit. Mother Teresa, the Roman Catholic nun and founder of the Missionaries of Charity who was canonized in 2016, worked and lived primarily at the Mother House from 1953 until her death in 1997. On the ground floor, a simple but elegant tomb marks Mother Teresa’s final resting place, and all are welcome to pay their respects.

The flavours and spices of Indian street food

I spent hours walking the streets of Kolkata, and found this to be the best way to get to know the city. I worked up a decent appetite, naturally, and fortunately found a number of good options right there on the street. A deep love of Chinese cuisine pervades the city, as is evidenced by the number of stalls selling 30-rupee plates of fried chow mein noodles. I walked up and down Circus Avenue near my lodgings and indulged in another favourite, crunchy fried pakora made from chickpea flour (20 rupees) and sprinkled with spicy salt. Generous 10-rupee cups of spicy, milky tea are nearly omnipresent.

The area around the Hatibagan Market, several blocks of sprawling chaos containing seemingly anything you could possibly want to buy, is another prime area to seek out street food. Navigating beeping cars and buses, gleaming displays of wristwatches and knockoff Tommy Hilfiger shirts, I found a sweet, earthy cup of freshly-squeezed sugar cane juice (30 rupees for a large cup). Down the street, I indulged in aloo chop, a deep-fried latke-like treat made from shredded potato and held together with chickpea flour (20 rupees for four pieces).

A word about street food: Be careful. A nasty stomach bug can potentially ruin a trip. If you’re going to risk it, look for places to eat that are busy and churning out food — it’s a good way to ensure it’s fresh. Be wary of fresh produce and raw food items, and don’t drink things that contain ice. The tea on the street, however, is frequently kept at a rolling boil, making it safer than some of your other options. If you have doubts, don’t eat it.

Indian street food is a veritable wonderland of flavour and spice. The use of mustard oil distinguishes local cooking, giving certain dishes a vaguely sinus-clearing quality, like eating wasabi. Jhal muri (30 rupees) is one good example, and the one I picked up north of the Victoria Memorial, a spicy concoction of puffed rice, chilli sauce and diced vegetables, certainly caused me to break a sweat.

The restaurant Peter Cat on chic Park Street is a popular, meat-centric option for those wanting a more formal dining experience. I also had a fantastic meal at the upscale Oh! Calcutta, on the fourth floor of the Forum Mall, enjoying a freshwater bhekti (barramundi) prepared in a piquant fermented mustard sauce (675 rupees) with a local gobindobhog rice.

But it’s the humble confection that might distinguish Kolkata, and its cuisine, more than any other food item. The city’s deep love of sweets is demonstrated in the number of shops peddling different varieties of sandesh (made from sweetened curd), coconut-covered cham cham, and mishti doi, a tangy, yogurt-like dessert. An assortment box at Girish Chandra Dey & Nakur Chandra Nandy, one of the oldest and most revered sweet shops in the city, cost 270 rupees.

It turns out that Kolkata, in addition to being India’s cultural heart, also has a fierce sweet tooth.

The New York Times Service

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)