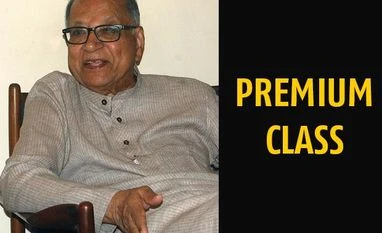

Just two steps into a simple single storey building in Salt Lake, Kolkata, sits the live history of insurance in India. It’s an autumn morning when I ring the bell for Arun Chandra Mukherji, expecting the nonagenarian to take a while to open the door. He surprises me, appearing instantly.

“You will live a hundred years,” he tells me cheerfully. Before I can think of a suitable comeback, the former chairman of New India Assurance Company escorts me to the living room. I marvel that he did not once wince while climbing the steps. Many stop doing so way before his age, I tell him. Mukherji had joined the company, then a Tata group enterprise, on 16 August 1948.

He recalls that this was barely two years after Direct Action Day — an infamous period in Kolkata when thousands were killed in pre-Independence riots. He had witnessed that dark day as a college student.

While he is a treasure trove of stories, my journey to his home is to tap into just one of those: his ringside view of how India’s general insurance sector has evolved since that morning of 1948 when he first became part of it.

“The Indian insurance sector was already quite developed when our batch of 10 management trainees joined New India Assurance,” he says. After World War II, as the Japanese economy lay prostrate, its leading insurance firm, Tokyo Marine, desperately needed foreign exchange to buy reinsurance, essential to offer any domestic insurance cover. Mukherji said his boss, New India Assurance Managing Director B K Shah, offered Tokyo Marine reinsu-rance cover but treated it as a loan payable after five years. The relieved Japanese firm used the model to buy similar cover from Lloyds and others. With that, India’s honeymoon with the Asian insurance market was firmly established.

In another two decades, Indian non-life insurers would go on to set up businesses from South Africa to Indonesia. A manager posted in Kolkata with a company such as New India Assurance could count as his region a wide arc of nations that comprise today’s Southeast Asia.

Mukherji is, however, not willing to sit down for a comparison of the good ol’ days with the post-nationalisation period. By the time he became chairman of India’s largest general insurance company in the late 1970s, the sector had already been taken over by the government. Under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the entire financial sector was nationalised, as were some other sectors such as coal, oil and even trade in commodities like wheat. “When the life insurance business was taken out of New India and others like Oriental Insurance to form Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) in the 1950s, (the then) finance minister C D Deshmukh had told us that general insurance was a matter between the business of buying and selling of insurance. And that the government wasn’t particularly interested in getting into it.” By 1966, the opinion in New Delhi had changed.

My research tells me that Mukherji was part of a select band of officers who offered a blueprint to the government about the holding company concept in general insurance. I ask him if it was on his suggestion that the four public sector general insurance companies were registered under the Companies Act — unlike LIC that became a corporation, which meant that any change in it had to be approved by Parliament. The General Insurance Corporation of India, as their holding entity, became a private limited company with shares fully held by the government of India. Mukherji, however, declines an answer to this. Instead, he points out that unlike coal or even banks, nationalisation of the general insurance sector went through smoothly.

Did the change impact the sector adversely? He doesn’t think so. There were gains and losses. The gains were the formation of strong companies instead of failure-prone puny ones. One of the losses was the gradual emasculation of the insurance sector from the overseas market. “The space for us was shrinking somewhat even earlier. As countries got their independence, they nationa-lised insurance,” he explains. “When we found we had to shut thpoliciesess of selling polices to people, we turned to reinsurance.”

Indian expertise had helped disparate markets such as Iraq and Africa to develop domestic insurance markets. Countries like Nigeria and Ghana, despite nationalising their insurance business, happily allowed Indian insurers to retain minority shareholdings in their domestic entity, but exercised management control. It wasn’t a total washout though. For instance, in the sub-continent, markets like Sri Lanka and Bangladesh have benefitted from the Indian experience. Within less than a month of Dhaka’s independence, Mukherji was part of an Indian delegation that allowed the new country to get major insurance cover. He is confident that with this background, the government’s recent aim to make India an insurance hub in South Asia and beyond is a feasible target.

There is an interesting sidelight to Mukherji’s foray into the overseas insurance sector. And it is visible on the walls of his book-lined home. “Wherever I went, I bought a local doll. The latest is from Uzbekistan,” he says, rummaging through the display shelves. It is a fantastic collection. He says he bought his first one when he was posted to Munich in 1954. It’s a plain German lass, made of wood. She now sits

Amid a veritable United Nations of dolls. Mukherji’s wife, Mridula, helps him discover their chronology. She was, incidentally, a classmate of former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, at the Delhi School of Economics. I realise it is easy to get distracted with stories in this house.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)